Orla Kiely's Life in Pattern

Jul 4, 2018

If you have visited London in the past month or two you might have noticed that the iconic facade of the Fashion and Textile Museum (FTM) has gotten a make-over. The re-design comes courtesy of Irish-born fashion and textile designer Orla Kiely. The FTM was designed by the renowned Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta Vilchis—it was the only European commission he completed. Its distinctive appearance epitomizes his talent for mixing brut Modernism with the Pueblo architectural style. The building especially stands out because of its vibrant pink, yellow, blue, and burnt orange color scheme. On the occasion of her mid-career retrospective, Orla Kiely: A Life in Pattern, Kiely has covered part of that famous exterior with her most famous pattern: “Stem,” which resembles a jungle of taut bean sprouts reaching upward towards the sky and sporting bulbous, rainbow colored leaves. “Stem” provides an additional spark of excitement to the structure. Yet is is inside the museum where the real spark of energy lies. The exhibition explores the broad range of work that Kiely has done over the past 20 years. The way the objects are displayed, however, does not read only like a design exhibition. It feels a bit more at times like an abstract art installation. The way the patterns and objects interact with the space and light creates an uncanny, and at times irreverent feeling. That sensation offers a perfect jumping off point for a larger question: “What are the barriers between contemporary art and design, and is it time for those barriers to be forgotten?”

The Reasons We Do What We Do

When debating whether to call someone an artist or a designer, one concept that inevitably comes up is intent: why does this person do what they do? According to traditional modes of thinking, artists are supposed to have loftier reasons than designers for doing things. The conceit basically says, “Designers make products that have a purpose, but art has no purpose, or if it does, it is a high highfalutin purpose that only the initiated and sophisticated can understand.” Orla Kiely is an example of why that supposition is wrong. Consider, for example, the work of someone else, whose name is quite similar to hers: the abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly. Throughout his career, Kelly took inspiration from plant forms. Many of his most memorable works are nothing more than pared down derivations of leaves and flower petals. Though considered a designer, and not an artist, Kiely also takes inspiration from nature, referencing the biomorphic shapes of leaves, flower petals, and stems. Ellsworth Kelly was not interested in pattern—he was more interested in individual shapes and forms. Kiely, however, frequently employs pattern as a visual tool. Regardless, the works of both Kelly and Kiely are capable of affecting the mood and attitude of viewers.

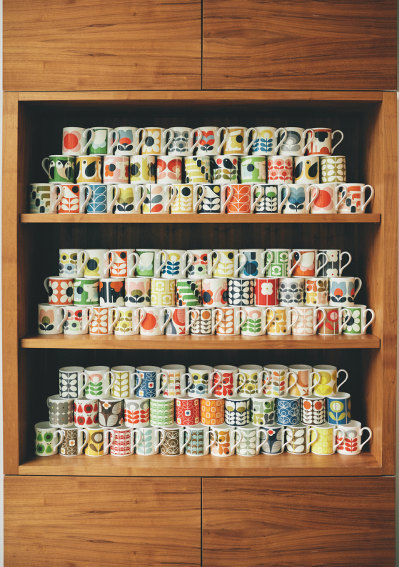

Orla Kiely - Mug archive 2007-2018. © Orla Kiely

So why is it that even though Kiely and Kelly are known for creating visual phenomena that looks similar and possesses the same emotive power, they are regarded as fundamentally different? Is it because designers create work for the mass market? Is it because designs are seen more as decoration or ornamentation, or as useful things? Can art not also be made for the mass market? Can art not function as ornamentation or décor? Even the most prominent fine artists make consumer products—they might only be affordable to wealthy collectors or institutions, not the masses, but they are commodities, nonetheless. What this exhibition demonstrates is that the intent behind a visual experience has nothing to do with its ability to affect human perception. Color is color, form is form, texture is texture, and line is line—our brain can perceive and react to aesthetic elements independently of the methods which such elements originated, or the reasons they were made.

Orla Kiely - Autumn/Winter 2017 Campaign. © Orla Kiely

Our Evolving Contemporary Environment

The curators for Orla Kiely: A Life in Pattern call the exhibition “a must-see for everyone interested in the changing look of the 21st-century environment.” There is a bit of hyperbole in that statement, but there is also something profound about it. The look of our world is changing, and in dramatically different ways depending on where we live, what our economic situation is, and whether our culture happens to be at war or at peace. Being surrounded by beauty and order is becoming more of a privilege than a right. The role of designers and artists in this transformation is evolving. Kiely is a designer whose work has been embraced by celebrities, but her range also includes extremely affordable pieces, and expands across a multitude of everyday items. If she and her colleagues can find more ways of reaching across social and cultural divides, beauty and order can become more ubiquitous.

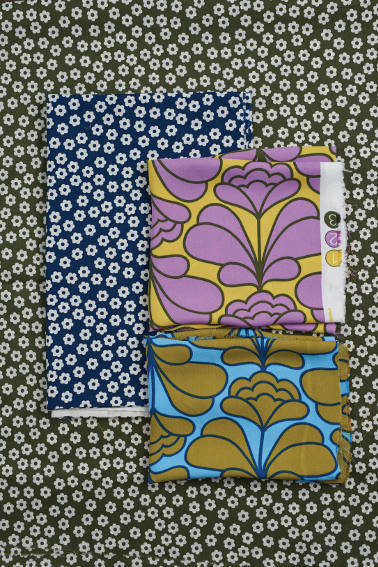

Orla Kiely - Spring/Summer 2016 Fabric. © Orla Kiely

For many of us, the “changing look of the 21st-century environment” is not what we would prefer it to be. One subtle thing that is within our power to change is the conceit that somehow art cannot be part of everyday life. If a painting can create a transformative emotional experience in the mind of a viewer, why could the visual experience of a set of curtains, a comforter, or a coffee mug not unlock similar perceptual doors? By the simple act of regarding ornamentation, decoration, and design not as separate from art, but as integral to art, we can extend beauty and order to anyone, regardless of their background or level of sophistication. That may not be a positive thing for the art schools, academicians, critics and institutions who define their value with artificial cultural separations, but it would be a positive thing for human culture at large. This one exhibition is not mandatory in order to comprehend this idea, but it is an eloquent addition to the conversation. Orla Kiely: A Life in Pattern is on view at the Fashion and Textile Museum in London through 23 September 2018.

Featured image: Orla Kiely - Spring/Summer 2017, New York Fashion Week. © Orla Kiely

By Phillip Barcio