Agostino Bonalumi’s Creative Path Through the Polyhedral

Jun 29, 2018

This summer, on the occasion of the five-year anniversary of the death of Agostino Bonalumi, the Royal Palace of Milan will present Bonalumi 1958 – 2013, the first survey of its kind in the city where the artist was born since he passed away. The exhibition unfolds chronologically, offering viewers the chance to trace his evolution from his early explorations of Arte Povera into his development as one of the most intriguing artists of the Zero Movement. Founded in Europe in 1958, the Zero Movement was a broad attempt to react against lyrical, emotional artistic tendencies such as Abstract Expressionism, which were prevalent in the decade after World War II. Zero Artists hoped to generate new possibilities for artists by establishing methods that were not dependent on emotion or individual personalities. Zero Art was intentionally devoid of expressionism. In the words of Otto Piene, who co-founded the group with Heinz Mack, the term zero was a way to express “a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning.” The movement began with the publication of a magazine called Zero, and eventually expanded to include a diverse assortment of art movements, including Nouveau Réalisme, Arte Povera, Minimalism, Op Art and Kinetic art, all of which shared common philosophical goals. Bonalumi made his unique contribution to the group by focusing on a technique he pioneered called “extroflection,” which has to do with polyhedrons and their ability to express mysteries perspectives on the potentially infinite dimensions that might exist in the physical world. Although the whole point of Zero Art was to avoid personal references to individual artists, the idiosyncratic nature of the extroflections Bonalumi created nonetheless make these works instantly identifiable as his own.

The Rise of Polyhedrons

Simply put, a polyhedron is a solid form that possesses more than one surface. Technically, a single flat object such as a piece of paper, or sheet of canvas, has more than one surface, but technically it is still not a polyhedron—it is a simple polytope. However, it you were to fold that flat sheet of paper, or flat sheet of canvas, and create a pyramid form, that would be a polyhedron. Basically, whenever any indentation or fold disrupts a flat surface in such a way that it creates a three-dimensional form that has multiple flat sides, a polyhedron has been created. Every polyhedron has its own name based on how many surfaces are formed by its indentations or folds. For example, a form with four flat planes is a tetrahedron; a form with eight flat planes is an octahedron; and so on.

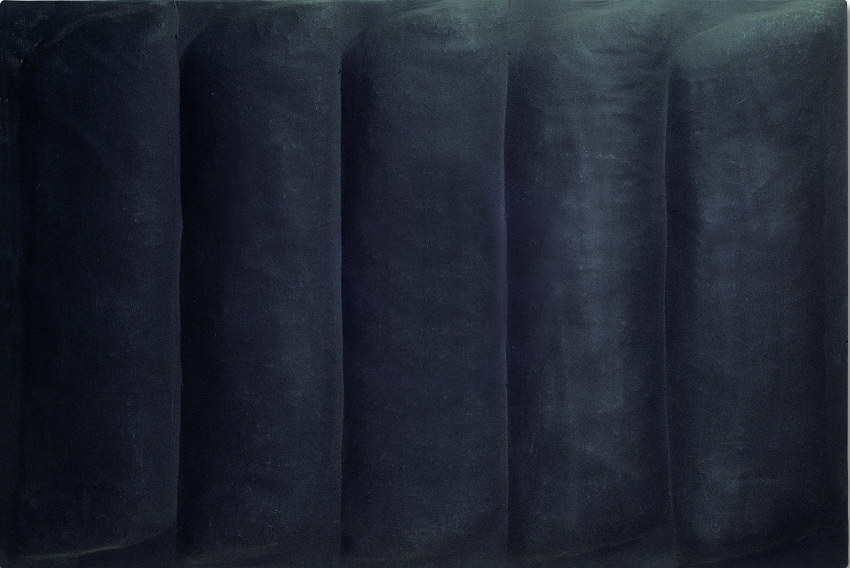

Agostino Bonalumi - Nero, 1959, 60 x 90 cm, Tela estroflessa e tempera vinilica. © Agostino Bonalumi

Why would an artist care about things such as this? Bonalumi was interested in polyhedrons because of the ways they express the forces and elements of the physical world. Specifically, he was interested in the way paintings were defined in part by their flatness. He sought to transform the flat surfaces of his paintings, creating polyhedrons and thus confusing their status as straightforward works of art, elevating them instead into abstract object paintings. He achieved this goal initially in the simplest possible way—by stretching the surfaces of his canvases taut and then inserting objects behind them that would protrude through the surface to create additional surfaces. The resulting polyhedrons may look simple, but actually they are quite complex, expressing space, form, dimensionality, color, texture, light and shadow—all through the straightforward act of disrupting a two-dimensional surface with pressure.

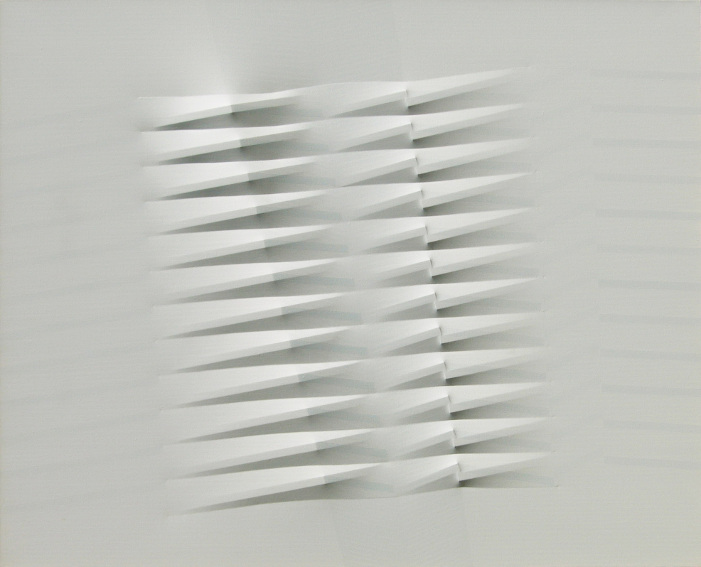

Agostino Bonalumi - Bianco, 1986, 130 x 162 cm. © Agostino Bonalumi

The Reach of Extroflections

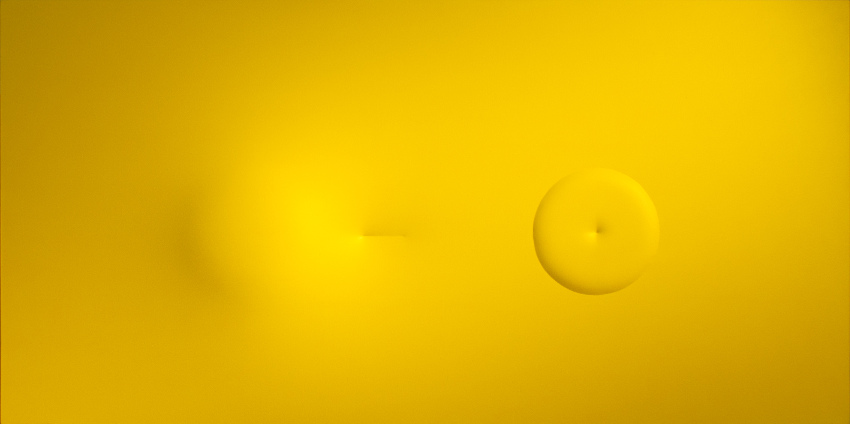

Bonalumi described his polyhedral works as “estroflessioni,” or extroflections, a word that communicated the idea that they are the opposite of things that bend backwards (which are referred to as retroflections). Extroflections bend forward, using tension to reach outward into space and time. In a sense, the act of extroflecting could be perceived of as a symbolic gesture of reaching towards the future. Bonalumi said as much about his works when he described their revolutionary disruption of medium and content, declaring, “the surface became the work of art.” To heighten this idea, he maintained a monochromatic palette for each extroflection, which he felt allowed the tensions and planes to full express their ability to disrupt light. By creating a ridge, extroflection alters the perception of hue simply by casting a shadow onto a plane. A monochrome thus appears to become multi-chromatic just by becoming multi-dimensional. This phenomenon challenges the definition of what a monochrome truly is by questioning the difference between color and light, if there really is any difference at all.

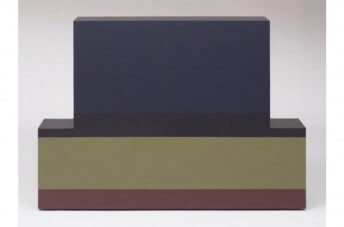

Agostino Bonalumi - Giallo, 2013, 100 x 200 cm. © Agostino Bonalumi

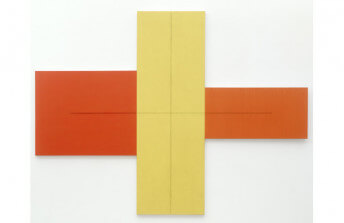

With such experiments, Bonalumi proved that it was not only his physical artworks that extended forward, but his concepts as well. The intellectual aspect of his work is especially clear in Bonalumi 1958 – 2013. Among many other works, the exhibition features three seminal, large-scale works that Bonalumi created in the late 1960s. The first, “Blu Abitabile” (1967), which translates into “Inhabitable Blue,” is 300 x 340 centimeters in size. As its name suggests, the work expresses color as a concrete element capable of encompassing space and supporting life. The other two—a pair of massive fiberglass extroflections titled “Nero” (Black) and “Bianco” (white)—premiered in a room-sized installation Bonalumi created for the 1970 Venice Biennale, and were recreated for this show. “Nero” is 6 x 12 meters, and “Bianco” is more than 25 meters long. Essential to the these works is their massive scale. Their physical presence exerts undeniable power over the human form. Because of their ability to transform and challenge the space that supposedly contains them, they perfectly embody the unique ideas for which Bonalumi is remembered: they prove that tension can be transformed into a medium, that space can become content, and that a surface alone can be elevated into a work of art. Bonalumi 1958 – 2013 will be on view at the Royal palace of Milan from 13 July to 30 September of 2018.

Featured image: Agostino Bonalumi - Blu abitabile (inhabitable blu), 1967, 300 x 340 cm. © Agostino Bonalumi

By Phillip Barcio