The Revolutionary, Yet Overlooked Weavings of Otti Berger

As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus this year, it is a fitting time to remember the inspiring, yet tragic story of Otti Berger, one of the most influential women to study and then teach at the Bauhaus. To many people, the Bauhaus is considered a hallmark of progressive culture. And indeed, the artists who studied and taught there were modern in both their art and their politics. And yet, there was still some prejudice against female students. We know from the career of Anni Albers that female students were usually forced to study the field of textiles at the Bauhaus, instead of being offered classes in painting, sculpture, architecture or design. Albers turned her study of textiles into one of the most influential art careers of the 20th Century, and revolutionized art education in the process. Otti Berger could easily have followed in her footsteps and had an equally influential and successful career. Like Albers, Berger was forced to study in the textile department of the Bauhaus. Also like Albers, Berger was adept at creating pared down, geometric compositions that gave her weavings a minimal, abstract sensibility. And finally, like Albers, Berger was a genius, becoming one of only a few Bauhaus artists to have her designs patented, while transforming the way textiles are viewed as an artistic medium. What stopped Berger from attaining the same public and critical acclaim as her colleague Albers is that Berger was killed by the Nazis. Despite her best efforts and those of many of her Bauhaus associates, she was deported by the Nazis to Auschwitz along with her family, where she was killed in 1944.

Overcoming Misunderstandings

Berger died when she was only 46 years old. The many accomplishments of her short life would have been impressive even under the best circumstances. They are all the more so when we realize the various struggles and misunderstandings she faced along the way. The first was that she was hard of hearing. In an age when few technologies existed to help her hear, she was put at a constant disadvantage in school, at work, and in social situations. She nonetheless succeeded at the Bauhaus despite this hardship. She not only excelled as a weaving student, she even developed new techniques for her craft. After finishing her studies, Mies van der Rohe was so impressed with Berger that he made her the deputy of the bauhaus textile workshop. After that, Berger left the Bauhaus and set up her own business in Berlin, where she designed textiles that were produced by several different companies. She was growing more successful each year until 1936, when she started to face serious pressure to get out of Nazi territory because of her Jewish heritage.

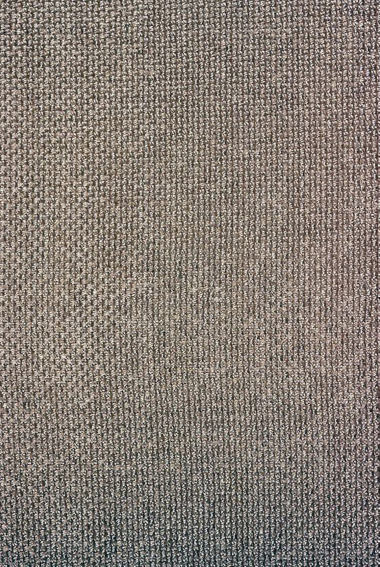

Otti Berger - Sample (Upholstry Fabric), 1919–1933. Cellophane and cotton, warp-float faced float weave backed by weft-float faced twill weave of supplementary warps and wefts. 43.1 x 37 cm (17 x 14 1/2 in.). Gift of George E. Danforth. © Art Institute Chicago.

By that time, many of the other Bauhaus teachers had already gotten out of Germany. Several had gone to the United States, and Berger intended to follow in their footsteps. She managed to escaped to London where she waited for several years to acquire a visa to travel to America. László Mohloy-Nagy was waiting for her in Chicago, where he had invited her to come and teach at the New Bauhaus he was setting up there. Unfortunately, her hearing problems made it quite hard for Berger to learn new languages. Her inability to effectively learn English made her time in London quite lonely. Things in were made even worse by the other great misunderstanding of her life: her national origin. She was born in 1898 in Zmajevac, a municipality in modern day Croatia. At that time, the city was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was known by the Hungarian name Vörösmart, so when she first came to Germany, Berger was misrepresented as being Hungarian. Yet when she arrived in London from Berlin, instead of being regarded as Hungarian, Jewish, or Croatian, she was simply considered a German. The English considered her the enemy. So as she waited in London for a visa that would never come, she was unable to hear or speak well enough to make friends, isolated from her colleagues who had all successfully gotten out already, and even separated from her family back home.

Otti Berger- Book, mid 1930s. Cotton. 3 3/4 x 9 1/2 in. (9.5 x 24.1 cm). Rogers Fund, by exchange, 1955. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Muted Abstraction

Despite her suffering, the work Berger created belongs to a tradition that has its roots in the Utopian, constructive, pared down geometries of Kazimir Malevich. Her early compositions are strongly rooted in the grid, and tend to embrace muted shades of black, white, grey, and brown. As she matured as an artist, her grids became more welcoming of deviations in design. She began to add more circles and other organic shapes. She also developed new techniques that allowed free flowing spots to develop in the work, where loose threads could expand among the tight weaving to take on shifting, biomorphic forms. Her method was both planned and experimental; rigid and free. Some of her most complex compositions even blend a structured foundation with hints of the lyricism she learned while studying with Wassily Kandinsky at the Bauhaus.

Otti Berger - Furnishing Fabric, 1925–1930. Cellophane and cotton, double woven plain weaves. 454.5 × 126.9 cm (179 × 50 in.). Gift of George E. Danforth. © Art Institute Chicago.

Though the majority of her oeuvre belongs to the world of textile design, we nonetheless should give it its due as fine art. After all, had Berger been allowed to go beyond the world of weaving at the Bauhaus there is no telling what other mediums might have appealed to her. Seen in the context of art, the most spectacular of her designs is “Knotted Carpet” (1929). Its stunning, colorful composition suggests a coming together of multiple aesthetic positions, from the lyricism of Kandinsky, to the structure of Mondrian, to the color theories of Albers. Like so many of her Bauhaus contemporaries, Berger was a master of subtlety when it came to formal aesthetic principles. She embraced the line, the square, the grid, and the power of color relationships. She believed in simplicity, and strived towards clarity. Had her life not been cut short by tragedy, there is no telling what more she could have added to the culture and history of abstraction.

Featured image: Otti Berger - Book, 1935. Cotton. 5-1/2 x 9 inches (14 x 22.9 cm). Rogers Fund, by exchange, 1955. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio