Otto Freundlich - A Revelation of Abstraction

The year was 1912. At age 34, the still relatively young Otto Freundlich, who had only recently committed himself to becoming an artist, had reason to celebrate. He had just sold a major new work to a private collector: a large, plaster sculpture, titled “Large Head,” evocative of the ancient, stone Moai of Easter island, but updated with distinctive, Modernist lines. The piece showed evidence of the influence Freundlich had received since leaving his Prussian homeland four years earlier, and relocating to the Montmartre neighborhood of Paris, where he had befriended many other young artists who lived there at the end of the Belle Époque, such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Amedeo Modigliani, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “Large Head” typified the interest those artists had in the indigenous art of Africa, Polynesia, and the Caribbean. Two years later their interests would shift radically, as World War I brought the Beautiful Epoch to an end. Freundlich carved out a unique position amongst his contemporaries, unabashedly advocating for abstraction as a constructive, spiritual tool for the betterment of humankind. In 1930, that collector back in Hamburg tried to cement the Freundlich legacy by donating “Large Head” to the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts. Yet, fortunes soon changed for both Freundlich and his art. The Nazis came into power, and in 1937 staged the so-called Degenerate Art, or Entartete Kunst, exhibition, which mocked all art forms which contradicted Nazi aesthetic tastes. “Large Head,” renamed by the Nazis “Der Neue Mensch (The New Man),” was featured on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. After touring with the exhibition, the piece was evidently destroyed, along with many other Freundlich works. In 1943, the Nazis also succeeded in destroying Freundlich, himself, who was Jewish, murdering him in the Sobibor extermination camp in Poland. However, as the monographic survey, Otto Freundlich (1878-1943), the revelation of abstraction, currently on view at The Montmartre Museum near where Freundlich once lived, proves, the beautiful legacy Freundlich created does indeed live on.

Utopian Views

It is a common occurrence these days to hear skeptics question the value of abstract art during troubled political times. To artists like Freundlich, such talk would have sounded absurd. In addition to being an avowed abstractionist, he was also a member of several of the most influential political art collectives of his generation. He was part of the November Group, so-named for the month of the German Revolution that ushered in the liberal Weimar Republic. Along with Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, he was also a member of the Workers Council for Art, which advocated for new ideas in the arts, as well as being a member of Abstraction-Création, a collective of abstract artists dedicated to undermining the influence of the mostly-representational Surrealists. Freundlich was not only politically active, he was able to hold many seemingly contradictory ideas in his head simultaneously, such as being an avowed communist, while also being totally convinced of the inherent spiritual condition of humankind.

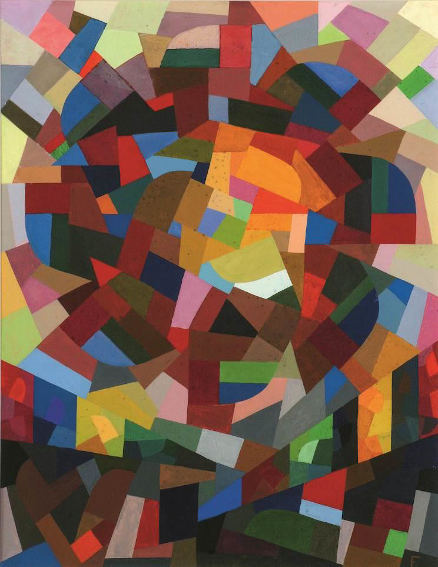

Otto Freundlich - Composition, 1930. Oil on canvas mounted on plywood, 147 x 113 cm. Donation Freundlich – Musée de Pontoise.

The value Freundlich cherished most was that of human freedom. Representational art, he suggested, establishes a cultural system in which society starts to feel it owns the images artists create, by virtue of everyone being able to recognize the images in the same way. This can create a foundation for societies and institutions believing they own other things, like citizens, or for citizens believing they own each other. Abstract art confounds this system of cultural ownership by remaining open to interpretation. If art is free, so are its viewers, and by extension their society. Certain formal strategies Freundlich used in his paintings reiterate his socialist beliefs: his compositions defy boundaries, extending beyond the edge of the canvas; his forms are not separated by lines, but rather meld into each other in liminal, blurred zones of color; and his shapes, forms, and color fields layer densely atop each other, creating a sense that unseen forces pulsate below the surface, supporting the images from underneath.

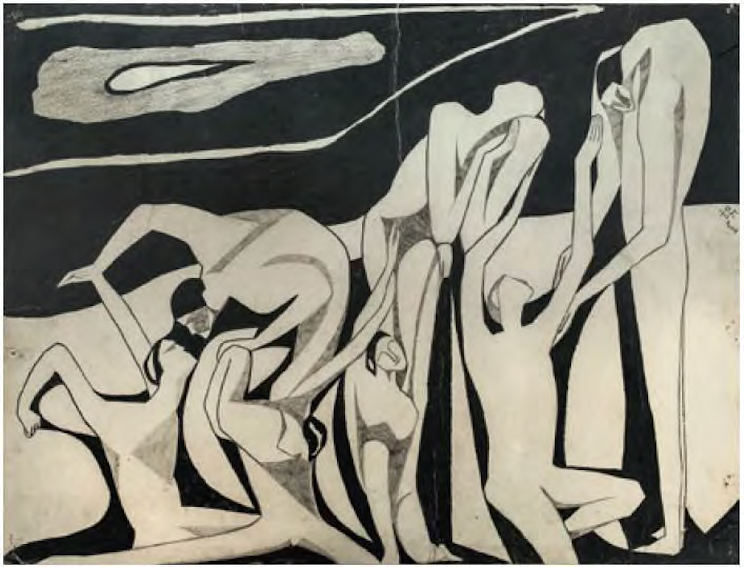

Otto Freundlich - Groupe, 1911. Black pencil on paper, 48 × 62,5 cm. Musée d’Art moderne de Paris.

The Unified Image

In addition to painting and sculpture, Freundlich was accomplished in the medium of stained glass. His admiration for the form can be traced to 1914, when he first visited the Chartres Cathedral, which possesses an unparalleled collection of preserved medieval stained glass windows. The translucent qualities of the glass helped Freundlich understand the potential for a two-dimensional, flat plane to express lightness and depth. The transcendent power of the cobalt blue, meanwhile, filled Freundlich with a belief in the spiritual power of art. Over the course of his career, he created several stained glass works. Three of those works are on view in the current Musée de Montmartre exhibition, with two more on display in the nearby Basilique du Sacré Coeur. The title of one of these pieces, “Tribute to People of All Colors,” points again to the pride Freundlich took in marrying his methods to meaning, as multitudes of forms and colors come together to collectively create a unified vision of beauty and light.

Otto Freundlich - Rosace II, 1941. Gouache on cardboard, 65 x 50 cm. Donation Freundlich – Musée de Pontoise.

In 1940, Freundlich wrote, “The truth which is the basis of all our artistic endeavors is eternal, and will continue to be of great importance for the future of mankind.” He wrote this after he was already aware that his works were being destroyed by the Nazis, and that his legacy, and his life, were in mortal danger. Few artists have the tenacity and grace to be able to make such unselfish statements while their own efforts are literally being erased. The 80 works that are on view in the current Musée de Montmartre exhibition are a reminder not only of the accomplishments of this artist, but also of the fact the evil that sought to hide those accomplishments from us is sadly still quite present in the world today. Is abstract art political? Of course it is. Especially when, like Freundlich, we have the courage to build on its universal, humanist ideas.

Featured image: Otto Freundlich - Composition, 1911. Oil on canvas, 200 x 200 cm. Musée d'Art moderne de Paris.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio