How the Works of Pat Steir Rose to the Top of the Art Market

Oct 6, 2017

Gallery representation is key for any artist intent on having a presence in the art market. But what exactly does a gallery do for an artist? And how do artists ensure they join the gallery that will give them the best representation possible? The story of Pat Steir may shed some light on the answers to these ancient questions. Steir has been a prominent figure on the American painting scene for decades. Her work is idiosyncratic, conceptually brilliant, and aesthetically stunning. But she has long been on the low end of sales numbers among other artists of her stature. But she was no late comer to the art market. The powers that be instantaneously recognized her abilities. The same year she graduated with her BFA from the Pratt Institute, she had her first group show—not at a gallery, but at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, arguably the most important art museum in the Southeastern United States. The following year she had group shows at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and MoMA in New York. Ever since, there has not been a year when Steir has faltered. Her work has consistently stunned viewers with its presence, its power, and its complexity. And she has even found time to teach at some of the most influential educational institutions in America, namely Princeton, Parsons, and Cal Arts. So the question is, why has Pat Reid not been rewarded financially for her success in a manner consistent with her importance as an artist? The answer, it seems, has to do with representation.

The First Gallery

Pat Steir was born in 1940. By 1964 her work had been included in three museum exhibitions, and she was offered her first solo exhibition in New York City, at the Terry Dintenfass Gallery. Terry Dintenfass was a native of Atlantic City, New Jersey. That is where she opened up her first art gallery, D Contemporary, in the lobby of what was then a premier seaside resort, the Traymore Hotel. But as Atlantic City experienced a decline in popularity, Dintenfass decided to shutter D Contemporary and move to Manhattan to open a new gallery. By doing so she became part of a growing wave of female gallerists in New York. She was among the most progressive, representing artists who were otherwise under-represented due to the pervasive social or political biases of the time.

The work that Pat Steir showed at Terry Dintenfass was not much in line with the prevailing aesthetic trends of the time. It tended toward figuration when minimal work was more in fashion. Not surprisingly, the exhibition did not generate enough sales to free her from her day job as an art director at the publishing company Harper & Row. For the rest of the decade Steir continued to exhibit her work in New York, but financial rewards continued to elude her. That was not the point for her, of course. Steir was in pursuit of something more important than money. She was establishing her own voice as a painter, and seeking to achieve something true as an artist.

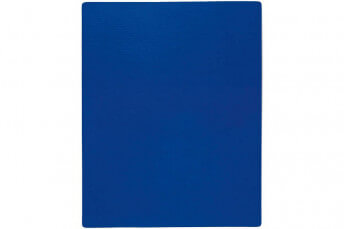

Pat Steir - Blue, 2007, Oil on canvas, 36 × 36 in, 91.4 × 91.4 cm, photo credits Bentley Gallery, Phoenix

Pat Steir - Blue, 2007, Oil on canvas, 36 × 36 in, 91.4 × 91.4 cm, photo credits Bentley Gallery, Phoenix

The Sea Change

In the early 1970s, Steir made a trip to New Mexico where she spent time with Agnes Martin. Conversations with Martin reinforced to Steir the importance of connecting with the spiritual aspects of what she was trying to do. She began to study the philosophies and artistic traditions of Eastern Asia. She connected their lessons with her own aesthetic tendencies, which were in line with the automatism and loss of ego inherentto Abstract Expressionist techniques. These influences culminated in a sort of new clarity for Steir, and in the early 1970s she created what became her first iconic series of works: her so-called rose paintings, abstract paintings containing forms suggestive of roses that were then crossed out. In describing what she was hoping to achieve in this body of work, Steir explained “I wanted to destroy images as symbols...no imagery, but at the same time endless imagery.”

Over the course of the next decade, this philosophical process Steir had begun led her to her most well-known body of work: her waterfall paintings. These works are the perfect conceptual demonstrations of giving up control, and yet also perfect expressions of planning and nuance. Visually, they look like paint poured down the front of a canvas, just like a waterfall. To make them, Steir hangs an unstretched canvas on the wall then climbs up a ladder to pour paint carefully down the surface. Gravity and time take over once she releases the paint. She commands the process. She chooses when, where, and how much paint to pour. She chooses the colors. She chooses the viscosity and whether to add additional brush marks or splatters. It is a simple, profound expression of humanity collaborating with nature. The process is harmonious, and so are the paintings.

Pat Steir - Mountain in Rain, 2012, Color direct gravure printed on gampi paper chine colle, 31 × 39 in, 78.7 × 99.1 cm, photo credits Crown Point Press, San Francisco

Pat Steir - Mountain in Rain, 2012, Color direct gravure printed on gampi paper chine colle, 31 × 39 in, 78.7 × 99.1 cm, photo credits Crown Point Press, San Francisco

Cheim & Read

By the end of the 1990s, Steir achieved mastery as a painter, and was offered representation by a major gallery: Cheim & Read, one of the most influential contemporary art dealers in New York. Located in the Chelsea neighborhood, Cheim & Read has been a fixture on the global contemporary art scene since they were founded in 1997. Any artist would see the chance to be represented by such a gallery as an incredible opportunity. But for Pat Steir, the opportunity did not pay off as hoped. That is not to say her works did not sell. They did, for tens of thousands of dollars. But many of her contemporaries were fetching ten times those amounts. Again, not that profit was her motivation. But in America, sales numbers profoundly affect whether an artist is accepted into the canon of important artists that regularly get featured in museums and biennials, and get added to the curriculums of art history classes.

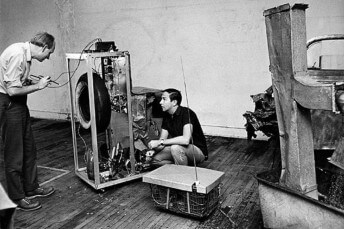

Enter Swiss-born art dealer Dominique Lévy. Lévy was born three years after Pat Steir had her first solo exhibition. She earned her Masters Degree from the University of Geneva in the fascinating subject of Sociology of Art. In the late 1980s and throughout the 90s she worked for Christie’s auction house, Sotheby’s auction house, and then once again Christie’s. Then in 2003, she opened her own art advisory service, called Dominique Lévy Fine Art.Two years later she opened L&M Arts with Robert Mnuchin, the father of the current Secretary of the Treasury for the United States. Then in 2013, she opened Dominique Lévy Gallery in Manhattan and London. There, she represented the estate of , and Yves Klein artists like Frank Stella and Pierre Soulages. And in 2016, she signed Pat Steir.

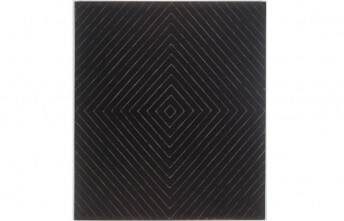

Pat Steir - Moment, 1974, Oil on canvas, 84 × 84 in, 213.4 × 213.4 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Pat Steir - Moment, 1974, Oil on canvas, 84 × 84 in, 213.4 × 213.4 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

What Is In a Name

Right after signing Pat Steir, Dominique Lévy partnered with British art dealer Brett Gorvy to form a new gallery: Lévy Gorvy, with offices in London, New York and Geneva. Lévy Gorvy is now who represents pat Steir. And since that merger, in the span of less than two years, prices for works by Steir have skyrocketed. In just the past six months, three of her works at auction have shattered their estimates. Sotheby’s sold Four Yellow Red Negative Waterfall (1993) for £680,750 after an estimate of £200,000, and both Misty Mountain Waterfall (1991) and Silver Moon Beam (2006) for £299,400 each after estimates of £113,250 each. In addition, Lévy Gorvy is selling new works by Steir for well over half a million each, a price point reached at Chicago EXPO where an untitled Steir painting from 2004 sold for $550,000.

So what happened? If Steir was capable of fetching these prices, why did Cheim & Read not make it happen? The answer could come down to connections. Every gallerist has a network. Maybe Lévy and Gorvy simply know different people. Or it could be timing. Perhaps this was bound to happen regardless of who represented Steir. Or it might come down to trust. Maybe Lévy and Gorvy have a track record that major buyers are betting on. But after looking over the gallery pages for Pat Steir on both the Cheim & Read and Lévy Gorvy websites, I think the difference might be one of understanding. The marketing materials Lévy Gorvy has put together are not only more modern and more comprehensive. The story they tell is also more sympathetic. It is my opinion that the number one determining factor in whether an artist has found the right gallery is whether the people who work at that gallery understandthe work. It is impossible to trick someone into buying art. But if a gallerist truly believes in the work they are selling, it becomesnot sales, but a matter of connecting people with art that matters to them, a feat that becomes possible because the buyer, the gallerist, the artist and the work, for whatever reason, speak the same language of the heart.

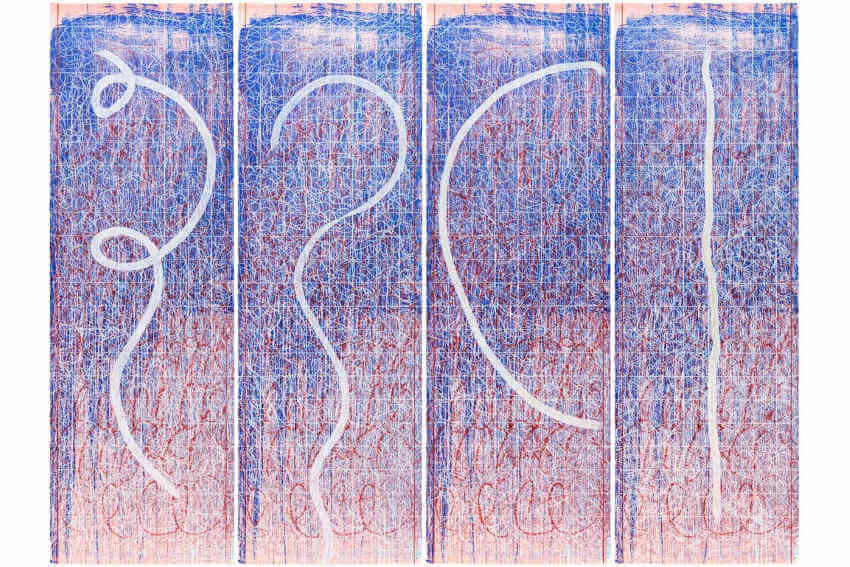

Pat Steir - Set of Four Lines, 2015, A set of four screenprints with hand-painting, 72 × 96 in, 182.9 × 243.8 cm, Unique

Pat Steir - Set of Four Lines, 2015, A set of four screenprints with hand-painting, 72 × 96 in, 182.9 × 243.8 cm, Unique

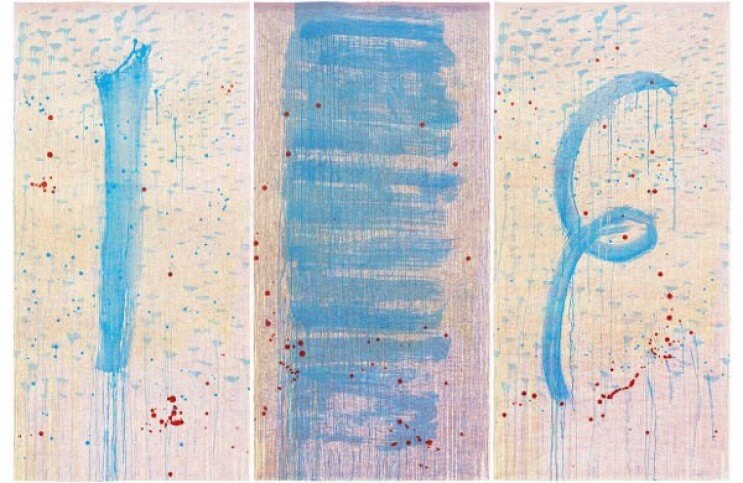

Featured image: Pat Steir - A set of three screenprints with hand-painting, 72 × 108 in, 182.9 × 274.3 cm, Unique, photo credits Pace Prints

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio