How Paul Strand Wielded Photography into a Channel for Abstraction

It’s strange to think that some people consider photography to be a purely technical craft, and not art. An artist invented the medium after all. In the hands of photography’s most famous practitioners, people such as Cindy Sherman, Ansel Adams, Man Ray and Paul Strand, photography has been utilized to create some of the most culturally influential imagery of the past two centuries. One of those photographers, Paul Strand, even accomplished something few other photographers have, something most probably never even thought about: the creation of abstract photography.

The Birth of Photography

Since ancient times, humans have known that an image could be projected onto a surface through a hole. Way back in 400 BC, the Chinese philosopher Mo Di made reference to the use of what we would now call a pinhole camera. And about 1450 years after that, his countryman Shen Kuo became the first to write about using a device that we would now call a camera obscura, a rather elaborate box with a hole cut in it through which a detailed reverse image can be projected.

Our ancient ancestors were also aware that once projected, that image could be traced for an exact replica, which is just one tiny step away from the idea of photography. Interestingly, ancient humans also knew that some materials were light sensitive, meaning they changed visually when exposed to light. But it wasn’t until the 1800s that these two concepts came together, as European artists and scientists began contemplating how images projected through a camera obscura could be captured through the use of light sensitive materials.

Though several different people were experimenting with this idea simultaneously, the first person to successfully develop a reliable, easily reproducible photographic method was a French painter named Louis Daguerre. Prior to experimenting with photography, Daguerre was known for his realistically detailed, sensuous oil paintings, which displayed masterful technique and employed a strong sense of lightness and darkness (chiaroscuro).

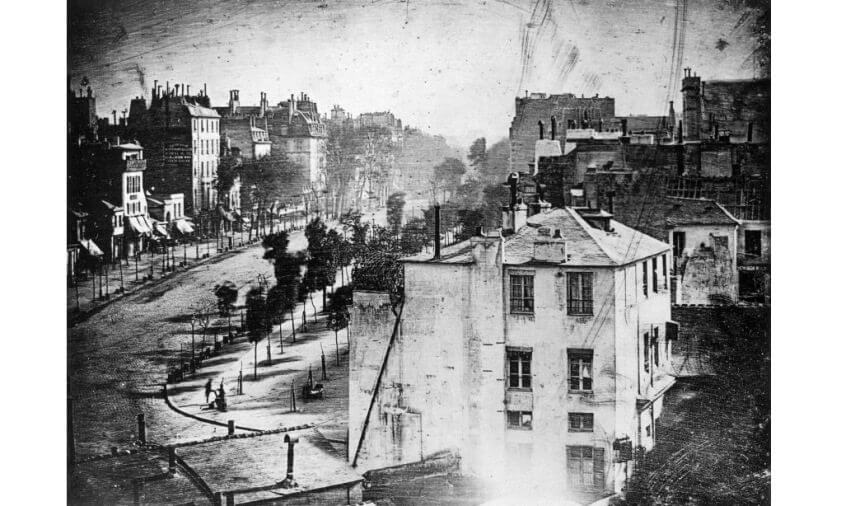

Louis Daguerre -Boulevard du Temple,1838,Daguerreotype (Photograph)

Daguerre and Niépce

Around the late 1820s, Daguerre began working with a French inventor named Joseph Niépce who had managed some successful proto-photographic experiments. Together Daguerre and Niépce developed the techniques that led to the invention of photography. Niépce unfortunately died before the process was fully realized. Daguerre ended up calling the first photographic images he made with their process “Daguerreotypes.”

Daguerre’s earliest snaps were of white sculptures. Was that choice a statement about photography as art? Or was it simply because the sculptures reflected a lot of light, and were thus adequate subjects for demonstrating the medium’s potential? We can’t say, since almost all of Daguerre’s notes and most of his early photos were destroyed in a studio fire shortly after he revealed his invention to the world in 1839.

Louis Daguerre -The Ruins of Holyrood Chapel, 1824, Oil on canvas, 83.07 x 100.98 in

Louis Daguerre -The Ruins of Holyrood Chapel, 1824, Oil on canvas, 83.07 x 100.98 in

Paul Strand, Photography and Art

By the time Paul Strand was born in 1890, photography had become ubiquitous. But somehow, even though the medium’s inventor was a professional artist, and the earliest photographs were of works of art, and countless other artists had experimented with the medium since its invention, still there was a general prejudice among academics and institutions that photographers were technicians, not artists, and that photography was not art. The photographer who changed that perception once and for all was named Alfred Stieglitz.

As a photographer, Stieglitz was a master of pictorial photography, the goal of which was to alter photographs artfully through chemistry and technique to show the photographer’s individualized perception, rather than capturing precise representational images. As a theorist, Stieglitz argued that the artistic qualities of photography should be widely accepted, and that photographs should be exhibited in museums and appreciated side by side with paintings and other forms of art. Finding that idea utterly rejected by the mainstream, in 1905 Stieglitz opened his own tiny museum, the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, at 291 5th Avenue in New York, where he spent the next 12 years promoting photography as fine art.

Shortly after it opened, Paul Strand visited Stieglitz’s gallery while still in school, and remarked upon leaving that he knew for certain that he wanted to spend his life as a photographer. Eventually Strand had the honor of exhibiting his work at Stieglitz’s gallery, becoming one of the last photographers the gallery championed before closing.

How Is Paul Strand Photography Abstract?

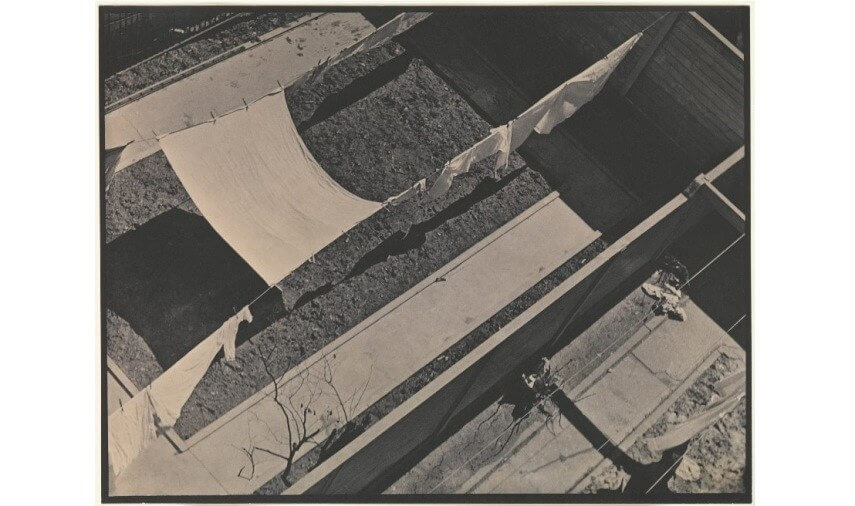

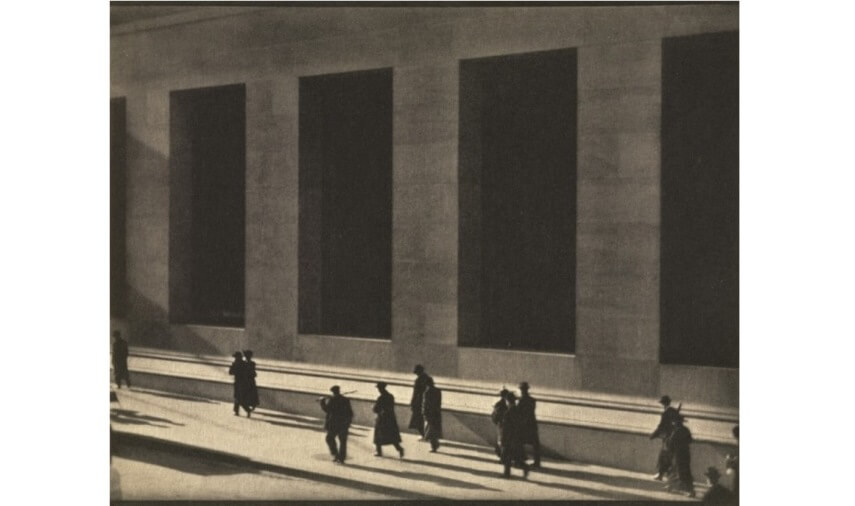

Strand’s early photographs were nothing like the work Stieglitz had been showing previously. Their sharp lines and alienated subject matter was representative less of pictorial photography, which made photography respected by the public as art, and more representative of what at the time were the current abstract trends in painting.

Paul Strand -Geometric Backyards, New York, 1917, Platinum print, 24.6 × 32.6 cm, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

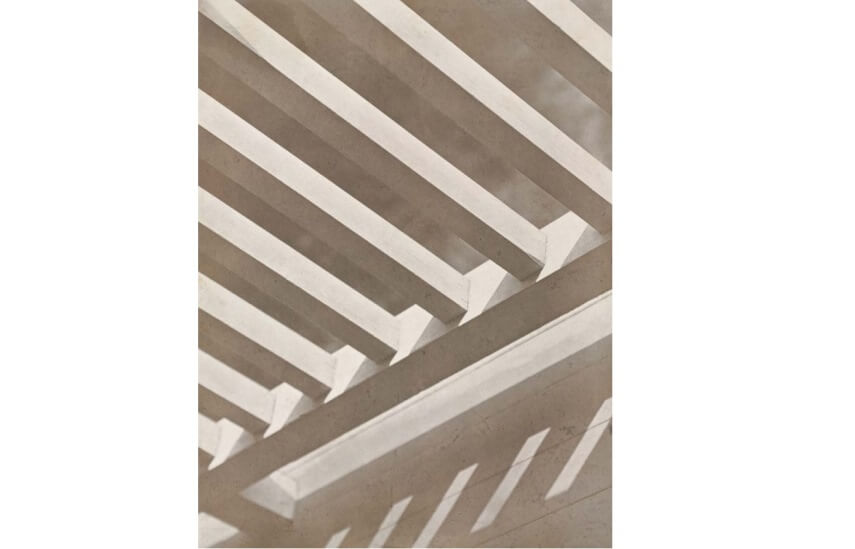

Imagine a photograph of a fence in the sunlight. The fence is real, representational; the sun is evident, the shadows obvious. In Strand’s photographs they combine to become something else. These transient things, the shadows: are they less real than the fence that caused them? Are they the subject of the picture, or is the light the subject? Is there any subject at all? Or is the photograph a study of line, form, shape, and chiaroscuro?

Strand’s photographs simplified photography. Rather than making it about the subject matter or the technique, he got people thinking about the two-dimensional products flowing from a four-dimensional process. Photography could be seen as a different kind of art, but definitely an art. Instead of building an image as a painter would, a photographer edits an image by selecting what a viewer will see. In that way a photographer is more like a sculptor than a painter, reducing mass to achieve an aesthetic result.

Like no other photographer before him, Strand achieved a fundamental objective of both photography and art: he showed the viewer more by showing less. What makes his works abstract isn’t only the composition, but also the feeling they impart, the ephemeral sense of life in a transient space. They’re uncanny. We recognize what we see in them despite it being incomplete and unclear.

Paul Strand New York, 1915, Photogravure, 13.2 × 16.4 cm, © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive

Paul Strand as Documentary Filmmaker

In addition to photography, Strand was an active documentary filmmaker. His films endeavored to show the everyday life of ordinary citizens, and how it relates to the places they inhabit. After World War II he left the United States and spent the rest of his life living in France, traveling extensively and photographing life throughout Europe and Africa. As an artist, his legacy is complex and multifaceted. A groundbreaking experimentalist early in his career, he later abandoned abstraction, choosing to explore the transformative social and political power of photography.

But throughout his practice, his work proved by its lasting relevance and continual presence in museums around the world that photography deserves equal respect among all other mediums as art. Strand’s artful eye, combined with his masterful technique and empathetic soul led to a body of work unlike that of any other artist.

Featured Image: Paul Strand - Abstraction, Bowls, Twin Lakes, Connecticut, 1916. Gelatin silver print. 33.1 × 24.4 cm. © Aperture Foundation Inc., Paul Strand Archive.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio