The Master of Day-Glo and Big Paintings - Peter Halley

It is tempting to talk about the work of Peter Halley solely in terms of its formal aspects—such as the Day-Glo and textured house paints he uses, the geometric language of shapes in his work, and the fact that he tends to work on a large scale. But to only talk about these elements ignores something vital—the deeper world of radical ideas from which his paintings emerge. Since the 1980s, Halley has been working with a single concept—the idea that human culture exists within prisons and cells, which are connected through conduits. Take for example our homes. An apartment building is a prison; the apartments are cells; and the utility lines are conduits. Or, for that matter, you could say each apartment is a prison; each room within the apartment is a cell; and the wires and vents between the rooms are conduits. And the analogy could continue, all the way to each of us. We are each a prison; our brains, our hearts, and each of our other organs are all cells; and the various biological networks connecting us to ourselves are just conduits.

Shapes or Ideas?

Halley expresses the concept of prisons, cells and conduits in his work with squares, rectangles and lines. He began doing this about four decades ago. At that time, he believed he was representing homes and offices being connected by phone lines and electrical lines—isolated people in isolated places in the city. Lately, the network of spaces and conduits has since grown exponentially more complex, both in reality thanks to over population and the information economy, and in his work. This is why we cannot talk about his paintings purely in formalist terms. Because he means for them to be seen as a criticism of the way we live.

As Halley says, our current social situation is “the latest incarnation of the tendency in Western culture, starting in the nineteenth century, to push us to become more and more physically isolated from one another, and to seek refuge in more and more disembodied social settings.” His paintings are attempts to get us to connect with this notion. But few people today respond directly or intuitively with that side of them. So what does that mean? So contemporary audiences simply lack interest in searching for deeper meanings in art? Are we only able to marvel at Halley as another master of the spectacle—a painter of very big geometric paintings illuminated by Day-Glo paint? Or have we have moved beyond the point of being disparaged that we live in a world of prisons, cells and conduits?

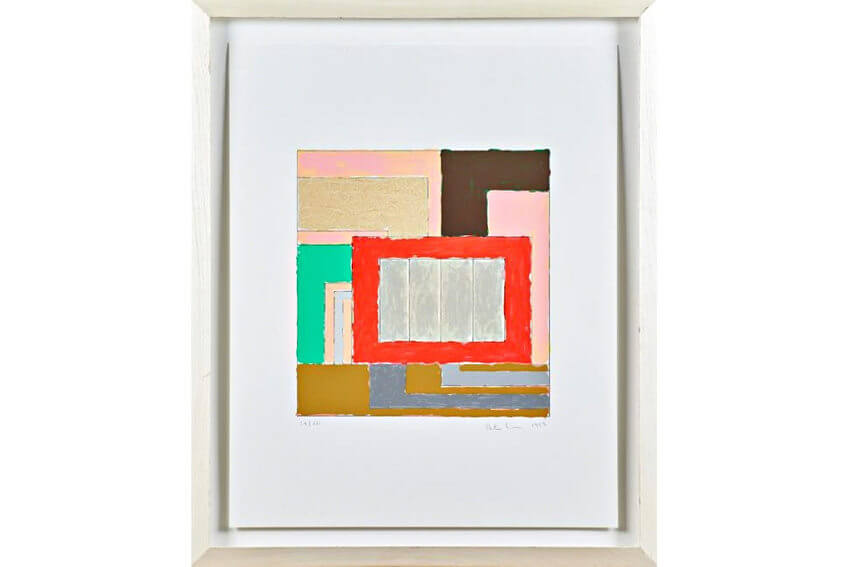

Peter Halley - Somebody, 1997, Silkscreen with Embossing on Arches Cover Paper (Framed), 19 1/2 × 15 1/10 × 1 in, 49.5 × 38.4 × 2.5 cm, Edition of 60, Alpha 137 Gallery

Peter Halley - Somebody, 1997, Silkscreen with Embossing on Arches Cover Paper (Framed), 19 1/2 × 15 1/10 × 1 in, 49.5 × 38.4 × 2.5 cm, Edition of 60, Alpha 137 Gallery

The Roots of the Concept

Halley cites two major influences in his art. The first is the Land Artist Robert Smithson. Halley is interested less in the specific value of Land Art, and more in the way Smithson talked about making art in general. As Halley says, Smithson was “completely committed to intertextuality–the mixing of disciplines and genres.” Smithson had a view of history that stretched beyond human culture, to include everything all the way back to primordial times. He believed that art could, and should, express the entirety of those concerns, not just the part that includes civilized humanity. He felt that all topics should fit together, and that no subject can be adequately discussed without interjecting elements of every other subject. This notion that all things are connected is a handy way of looking at the paintings Halley makes.

The second major influence Halley cites is The Society of the Spectacle, a work of philosophy published in 1967 by Guy Debord. About this book, Halley has said, “I emphatically believe that it is the crucial touchstone for contemporary art today.” The crux of the book is that human life is being degraded. Instead of having authentic experiences, people are gravitating toward symbolic experiences, which are then replaced by fictional experiences. Debord felt that authenticity was being replaced by a media-driven social construct based on homogenous narratives, into which people insert themselves in lieu of developing individual characteristics. The prisons and cells and conduits Halley paints relate directly to this concept. They are repetitions of a single, simple idea, which Halley believes is the most important topic of our time.

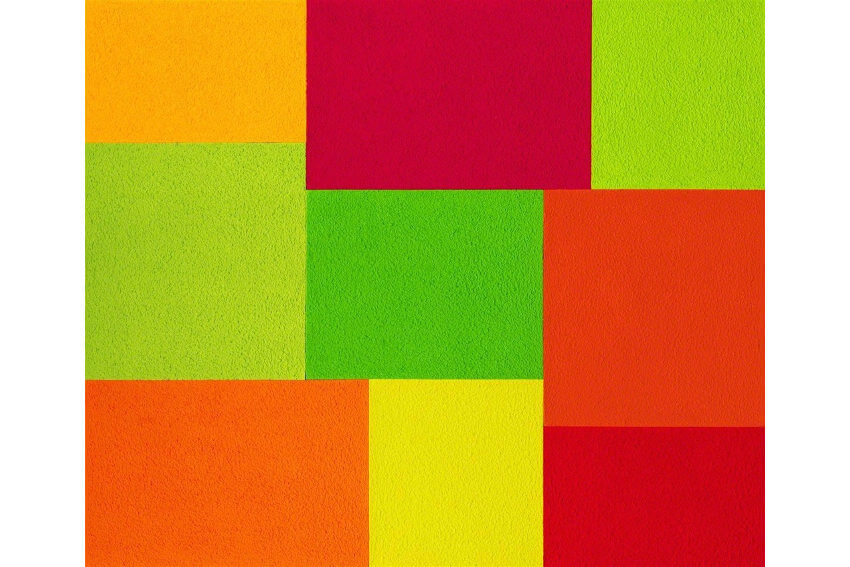

Peter Halley - Regression, 2015, Fluorescent acrylic and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, 72 × 85 4/5 × 3 9/10 in, 182.8 × 218 × 10 cm, Maruani Mercier Gallery

Peter Halley - Regression, 2015, Fluorescent acrylic and Roll-a-Tex on canvas, 72 × 85 4/5 × 3 9/10 in, 182.8 × 218 × 10 cm, Maruani Mercier Gallery

Aesthetically Speaking

Philosophically, I find Halley cynical. I believe his worldview, and that of Debord, is based on generalizations. But I love the images Halley creates. I love that humans are busy transmitting information and resources back and forth between their architectonic environments. An apartment is no more a prison to me than a brain is a prison. Both have limits, but both also have escape routes. I find the glowing luminosity of a large-scale Halley painting to be joyful. These works are like icons showing the natural way of the universe. I especially like when Halley breaks out of his mold, and makes the occasional explosion painting, or a painting in which squares and lines warp together into a psychedelic mess. These works show the end of one system and the beginning of another. They are the most optimistic, because they remind me that every structure and every process comes to an end.

I think it is especially prescient that Halley works with what he calls the “geometricization of space that pervaded the 20th century.” So many abstract artists are attracted to the language of geometry, each for different reasons. There is something about the shapes Halley presents—they are self-contained; they are precise; they are both abstract and concrete. They are starting points for contemplation, and yet they are also utile, on-the-nose things. I feel that Halley is trying to warn us about something sinister. But that vision is an illusion. Most of us do not live in boxes. We do not see our world as an amalgam of prisons, cells and conduits. I prefer to bask in the happiness I feel from these paintings—from their Day-Glo luminosity and their monumental scale. For some reason, to me, they feel alive.

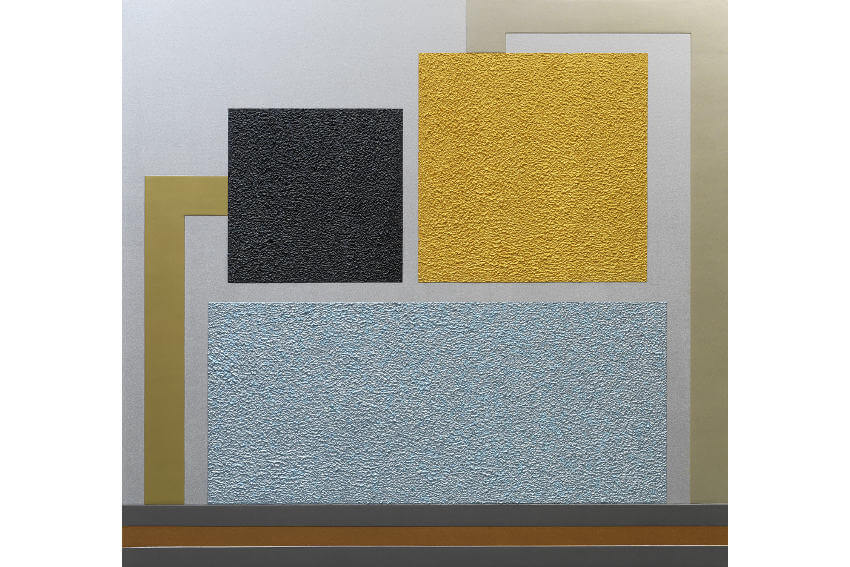

Peter Halley - Collateral Beauty, 2016, Metallic, pearlescent acrylic and roll-a-tex on canvas, 72 × 77 × 3 9/10 in, 182.88 × 195.58 × 10 cm, Maruani Mercier Gallery

Peter Halley - Collateral Beauty, 2016, Metallic, pearlescent acrylic and roll-a-tex on canvas, 72 × 77 × 3 9/10 in, 182.88 × 195.58 × 10 cm, Maruani Mercier Gallery

Featured image: Peter Halley - Friend Request, 2015 - 2016, Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, and Roll-A-Tex on canvas, 66 9/10 × 90 1/5 in, 170 × 229 cm, Galeria Senda, Barcelona

All images © Peter Halley, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio