How Photogram Introduced the Non-Representational to Photography

A photogram is a cameraless photograph: an image burned onto a photosensitive surface without the use of a machine. Photograms predate photographs. The earliest photographic images of reality captured with a camera were called Daguerreotypes. Named for their inventor, Louis Daguerre, they were first revealed to the world in 1839. Daguerreotypes were made by inserting a sheet of sensitized, silver-plated copper into a dark box then opening an aperture in the box and exposing the copper sheet to light. The image burned onto the copper was a precise rendering of whatever was in front of the aperture. At the time, Daguerre was one of a multitude of inventors experimenting with techniques for creating photographic images. Few ever arrived at something we would today call photographic. The method most of them discovered was simply to set an object directly on top of a photosensitive surface then expose the surface to light. The area not covered by the object would darken, while the area covered by the object would remain white, or grey correlating to the relative transparency of the object. Thus was born the photogram. Though the process does not result in a photorealistic image, it was nonetheless useful to 19th Century scientists like Anna Atkins, who, in 1843 used a photogram process called cyanotype to make botanical images for her book British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. And that same process also became helpful for the inexpensive reproduction of technical drawings, called blueprints. But it was not until the early 20th Century, when photographers began seeking ways to expand into the realm of abstraction, that the photogram became relevant as an artistic medium of its own, as a method of using light to create photographic images that stretch beyond the bounds of the representational world.

Rediscovering the Photogram

The artist most commonly credited with introducing the photogram to 20th Century art is Emmanuel Radnitzky, better known as Man Ray. Born in Philadelphia in 1890 then raised in New York City, Man Ray was a member of the crowd that hung out at the 291 Gallery, the Manhattan hub of new art owned by the early Modernist photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Through his associations at 291 Gallery, Man Ray became energized, and developed a particular attraction to the medium of photography.

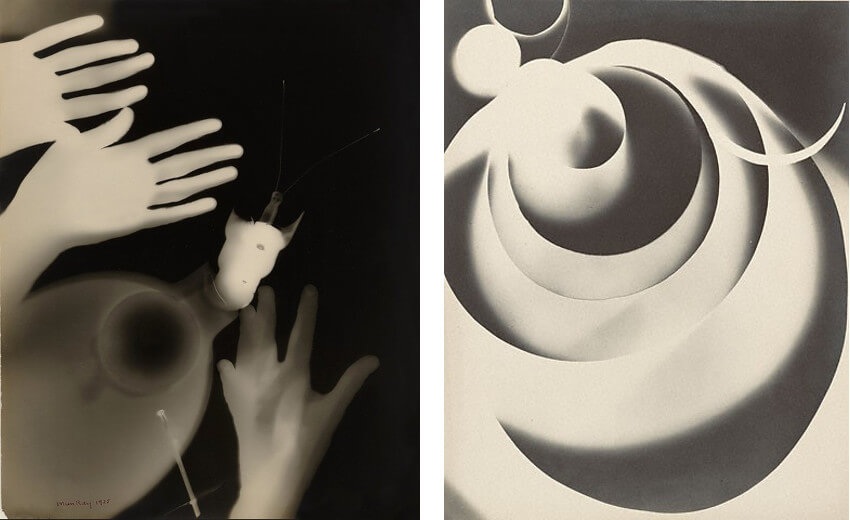

It was also at 291 Gallery that Man Ray made the acquaintance of Marcel Duchamp, the so-called “one man art movement,” with whom he collaborated to start the New York Dada movement. But after finding New York unreceptive to their ideas, Man Ray decided to leave America and move to Paris, saying, “All New York is dada, and will not tolerate a rival.” The move ended up being essential, for it was in Paris that his research led Man Ray to rediscover the lost technique of the photogram. By placing objects directly onto photographic paper then making multiple exposures with new arrangements of objects, he created layered ghostly, dreamlike images, which in his own honor he dubbed Rayographs.

Man Ray - Rayograph, 1925, Photogram (left) and Untitled Rayograph, 1922 (right), © Man Ray Trust ADAGP

Man Ray - Rayograph, 1925, Photogram (left) and Untitled Rayograph, 1922 (right), © Man Ray Trust ADAGP

The New Vision

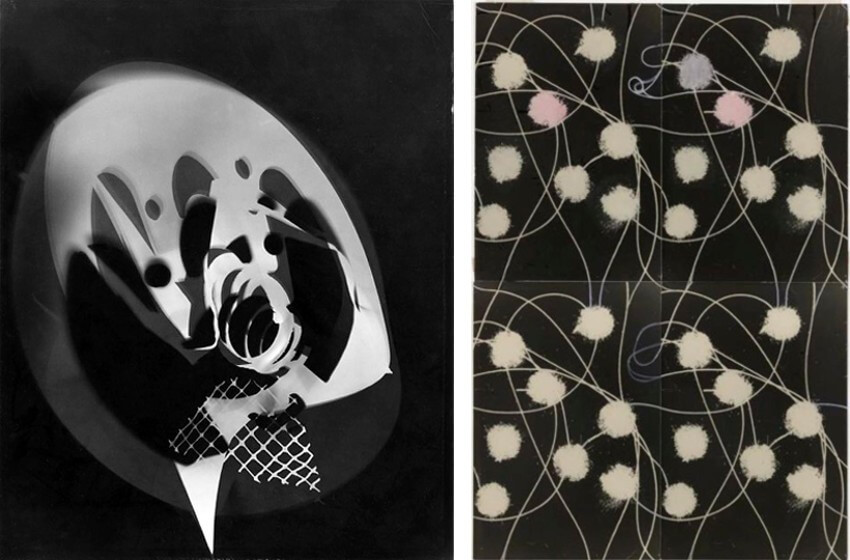

Meanwhile in Germany, photography was a major concern for many of the artists associated with the Bauhaus. It was seen as a thoroughly modern medium, and one intimately related to everyday life. It is no surprise then that several artists associated with the Bauhaus also embraced the idea of the photogram once they encountered it. The influential Bauhaus teacher László Moholy-Nagy experimented with the photogram using everyday objects as subject matter and taking multiple exposures to create abstract compositions.

In 1929, Moholy-Nagy helped stage the famous Film und Foto (FiFo) exhibition and included the photogram process as a prominent example of his Modernist agenda the Neues Sehen, or New Vision. He believed the process represented the unique aesthetic rules that applied only to photography. A student of Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus named Elsa Thiemann then expanded on his ideas when she used the photogram process to create wallpaper, something that in the spirit of the school used an aesthetic process to create a total work of art applicable to everyday life.

László Moholy-Nagy - Untitled Photogram, 1938, © 2018 The Moholy-Nagy Foundation (left) and Elsa Thiemann - Photogram Wallpaper Design, 1930, © Elsa Thiemann (right)

László Moholy-Nagy - Untitled Photogram, 1938, © 2018 The Moholy-Nagy Foundation (left) and Elsa Thiemann - Photogram Wallpaper Design, 1930, © Elsa Thiemann (right)

Contemporary Photogram Abstraction

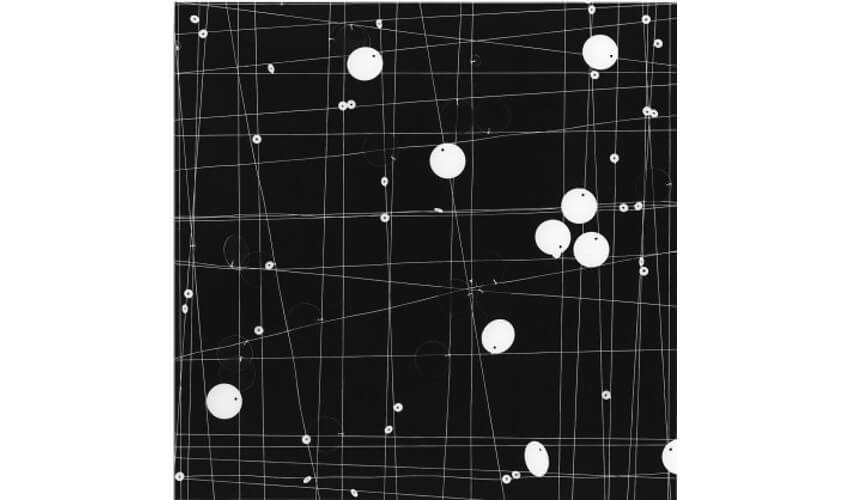

Today several contemporary abstract artists are pushing the boundaries of the photogram process. Brooklyn-based Canadian abstract artist Tenesh Webber takes the concept into new territory by deconstructing it to its most basic elements of surface and light. Webber uses the simplicity of the process to create her layered abstract compositions. She begins by placing thread across a two-dimensional, transparent surface, sometimes stretching it taut, and other times letting it fall into an organic state. She creates multiple surfaces, or plates, eventually stacking them to create a layered black and white photogram that blends a universe of organic and geometric propositions.

Tenesh Webber - Mid Point I, Black and white photogram, 2015

Tenesh Webber - Mid Point I, Black and white photogram, 2015

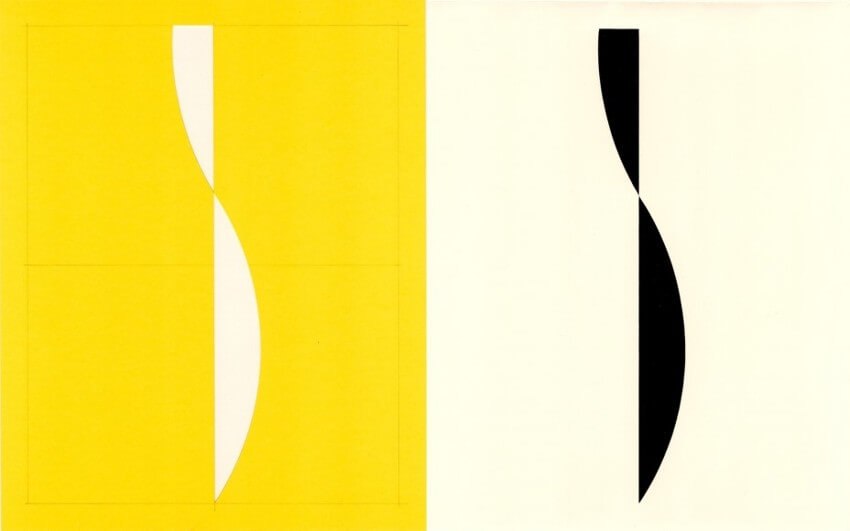

British artist Richard Caldicott uses photograms as one part of his ongoing examination of structure and geometry. Caldicott has explored photography from a number of different perspectives. He earned acclaim for his geometric abstract images of Tupperware, which eliminated the subject matter of the content, wholly objectifying the forms. And his Chromogenic color prints, or C-Prints, are the result of an innovative process of layering color negatives to create a refined expression of color, geometry and space. Caldicott makes photograms by cutting shapes out of paper and using the cut paper as a rudimentary negative. To further demonstrate his concept he also creates diptychs that consist of the paper negative on one side and the resulting photogram on the other.

Richard Caldicott - B/W photogram and paper negative (43), 2013 (right), © Richard Caldicott c/o Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

Richard Caldicott - B/W photogram and paper negative (43), 2013 (right), © Richard Caldicott c/o Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

Featured image: © Susanna Celeste Castelli, DensityDesign Research Lab, Polytechnic University of Milan

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio