How Queer Artists Used Abstraction to Express Themselves

A number of exhibitions are currently on view in consideration of Pride Month, as well as the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots—protests following a police raid of a gay bar in Greenwich Village, which sparked the modern gay rights movement. Particularly fascinating among them is Queer Abstraction, the first major exhibition in the United States devoted exclusively to the subject of queer abstract art. On view at the Des Moines Art Center in Des Moines, Iowa, the exhibition includes works by some of the most exciting names in contemporary abstraction, including Mark Bradford, Carrie Moyer, Sheila Pepe, Nicholas Hlobo and Elijah Burgher, as well as works by such legends as Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957 - 1996), Tom Burr and Harmony Hammond. The exhibition comes at a time when the category of queer abstract art is only beginning to be discussed by the larger art field. It can be a difficult category to navigate through, not only because of the difficulty in determining what exactly makes a work of contemporary art abstract—especially when it is rife with content—but also because what makes a work of art “queer” may not be as straightforward as it seems. At a recent symposium in Chicago, the artist Carl Pope offered examples of work by non-queer identifying artists that was in his opinion, “queer art.” The characteristics the works tended to relate to openness, inclusion, diversity, and an overall embrace of new structures of identification and individuation. Queer content does not necessarily have to relate to queer perspective, and vice versa. One of the things this exhibition in Des Moines achieves is it helps to make the delineation of the topic a bit more concrete, at least in one case: the artists included are all queer identifying. It pleasantly muddies the water, however, when it comes to the definition of what is, and is not, abstract.

Material as Message

Materials always come embedded with meaning, whether we realize it or not. The paint an artist uses; the surface on which they paint; the materials with which they sculpt—all of it carries a social, economic, political, and cultural message. This is one arena in which Queer Abstraction truly excels. A sculpture by Jade Yumang titled “Page 5” (2016) presents visually as an expert blending of aesthetic positions ranging from those of Jessica Stockholder to Louise Bourgeois. Upon closer examination, the mediums from which it is made reveal much more loaded content. A scanned page of gay erotica has been printed on cotton and polyurethane foam, lending the forms a distinctly sexual character; woven wool and zippers evoke an intimate human connection; pink acrylic paint blends into deep purple, suggestive of both the multi-cultural history of the artist, who was born in the Philippines and immigrated to Canada, and the transition of day into night, light into darkness, openness into hiding.

Jade Yumang - Page 5, 2016. Scanned gay erotic page printed with archival ink on cotton, polyurethane foam, woven wool, zippers, and acrylic on hemlock. 36 x 14 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist. Image courtesy of the artist.

Similarly, the work of Harmony Hammond brings materials strongly into play. Hammond first came to prominence in the 1970s, having moved to New York just months after the Stonewall Riots. She came out in 1973, and has always focused on making work that is abstract. The message of the work is embedded in the materials and the method. Using mediums like fabric, twine, paper and metal she assembles objects that clearly show the mark of their own making. Stray words or phrases may infiltrate the image-objects, sometimes directly declaring queer content, other times redirecting the subject matter. Often the work looks and feels worn and comfortable; eerily human. People often refer to her work as feminist, but its legacy lies equally in the traditions of Arte Povera, a trend in abstraction that speaks to the embedded meaning and content within the use of everyday materials in fine art. What Hammond does is an excellent example of how labels like feminist and queer are often insufficient and poorly understood.

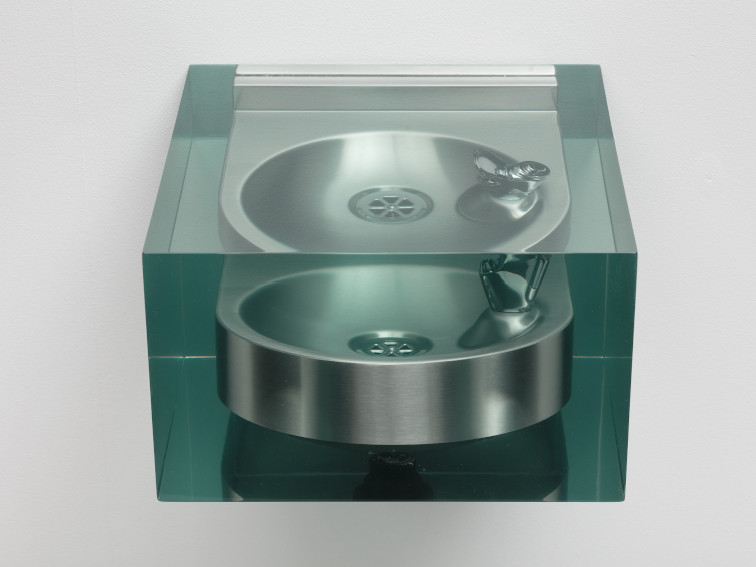

Prem Sahib - Roots, 2018. Steel drinking fountain and resin. 9 x 1 5 x 15 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Southard Reid. Photos courtesy of Lewis Ronald and Southard Reid, London. © Prem Sahib

Formal Gestures

Another vital aspect of Queer Abstraction is its recognition of queer contemporary artists who are pushing the boundaries of formal abstraction. The works of Carrie Moyer certainly lie on the forefront of this topic. Moyer has called what she does “cross wiring.” She blends a seemingly infinite number of art historical references in her work, from Surrealism to Bio-Morphism, to Hard Edge Abstraction to Minimalism and beyond. Her colorful, luminous works somehow employ the flattened languages of Modernist abstraction to open up worlds into which the viewer can enter. It is this cross blending of the past with the present, and the total innovation of a new painterly perspective, that makes Moyer one of the foremost living abstract painters. What is especially queer about her work, beyond the personal history of the artist, might relate to the spectrum of hue she employs; it might relate to the diversity it embraces; or it might relate to the emboldened bravery and experimentation that informs its creation.

Carrie Moyer - Fan Dance at the Golden Nugget, 2017. Acrylic and glitter on canvas. 66 × 90 inches. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY. Photo courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York, NY.

Works by other artists such as Edie Fake and Math Bass show how classic aesthetic positions from Modernist abstract history are being employed by queer artists in decidedly contemporary ways. Fake draws from Op Art, Hard Edge Abstraction, Geometric Abstraction, the Pattern and Decoration Movement, as well as Hindu art, Indigenous Art and other non western traditions. In addition to these formal aesthetic references, his complex compositions can be mined for symbolic and abstract content relating to non-binary and transgender culture. Bass meanwhile has developed an aesthetic position that evokes the legacy of Super Graphics, Minimalism and Geometric Abstraction. Her dynamic works speak to her history as a performance artist. They broadly mobilize two concepts that are integral to building an equitable society: movement and change. Each of these artists brings a unique perspective to two fundamental questions underlying the curation of this exhibition: what, if anything, makes an artwork abstract, and what, specifically, makes it queer. Queer Abstraction is on view at the Des Moines Art Center through 8 September 2019, and will then travel to the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art in Overland Park, Kansas, from 21 November 2019 through 8 March 2020.

Featured image: Edie Fake - The Keep, 2018. Gouache and ink on panel. 28 × 28 inches. Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections; Purchased with funds from the Keith W. Shaver Trust. Photo Credit: Rich Sanders, Des Moines.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio