Robert Delaunay and His Approach to Color

What does it mean to say a painting is “realistic?” Reality is a contested subject. It is purely subjective, after all. What one considers real is based on a combination of what one perceives, what one understands and what one can imagine. In 1912, the painter Robert Delaunay published an essay in the German periodical Der Sturm titled, “Notes On the Construction of Reality in Pure Painting.” The essay was an attempt to summarize the previous 60 years of artistic research, since the beginning of Impressionism, into the subject of how best to portray reality in art. Delaunay described the work of his predecessors as being scientific and analytical, breaking down painting into its components in order to arrive at the essentials of painted reality. He wrote how artists should only strive to create what is beautiful and that reality is the only truly beautiful thing. But reality, according to Delaunay, did not mean mimicry. Rather, he surmised that reality’s most basic and beautiful element was color, for nature, via light, conveyed the beauty of the world through color to our eyes, and that “it is our eyes that transmit the sensations perceived in nature to our soul.”

Color is Reality

One of the things Robert Delaunay was fond of saying about himself is that before him painters just used color for coloring. He believed he was the first painter to use color as a subject in itself. He gave credit to the Impressionists, because they were the ones who identified the importance of light. But they still only used the qualities of light to copy images of the objectively visible world. But at least they recognized that an image is made up of many different parts, and that it is the perception of those parts that creates a sense of what reality is. Perception happens not on the canvas, but in the brain.

Pointillism was the first, and most profound painting styles to really examine the fact that perception happens in the brain. Also known as Divisionism, it utilized small blocks of color placed next to each other on a canvas to convey the sense of a mixed color rather than mixing the colors together first. The brain would then combine the colors in order to complete the image. That realization, that the eyes and brain could complete an otherwise incomplete picture, became a founding principal of the late 19th Century and early 20th Century avant-garde. It inspired Futurist painting, Cubism, Orphism and innumerable other styles and movements since.

Color as Subject

Robert Delaunay was captivated by Divisionist thinking. It inspired him to think about the relationship colors have to each other when placed next to each other on the canvas, independently of what image they were being used to create. He enlarged the blocks of color beyond what the Pointillists had done, creating much more pronounced and abstracted visual effects. He used this technique to make a series of portraits of his friend and fellow abstract painter Jean Metzinger.

In Delaunay’s Metzinger paintings, we can see blocks of color creating depth and a sense of movement in addition to just forming an image. Through his Divisionist paintings, Delaunay realized that color could convey form, depth, light and even emotion. Independent of the figurative elements of an image, color could, on its own, convey any truth or any reality a painter hoped to express.

Robert Delaunay Rythme n°1, décoration pour le Salon des Tuileries, 1938, oil on canvas, 529 x 592 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Robert Delaunay Rythme n°1, décoration pour le Salon des Tuileries, 1938, oil on canvas, 529 x 592 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Color and Plane

While Delaunay was making his own discoveries about painted reality, the Cubists, led by Pablo Picasso, were also experimenting in a similar realm. They were attempting to convey four-dimensional reality and the passing of time. Their method was to divide the world up into spatial planes and then use those planes to express a multitude of simultaneous points of view on a single subject.

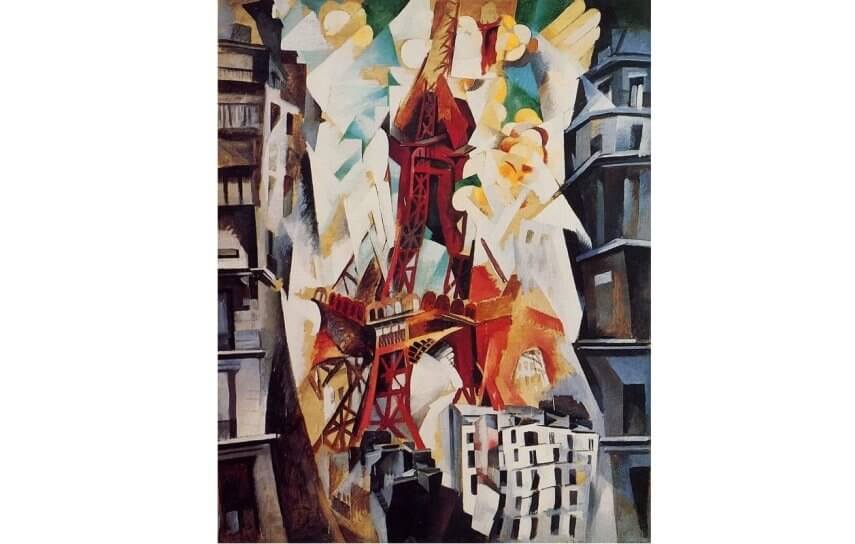

Delaunay was not interested in perspective. He believed that through color alone movement, or any other phenomena, could be expressed. But Delaunay was nonetheless intrigued by the Cubist idea of spatial planes. He had noticed that when light hits things, the various hues that appear are determined by the geometry of their spatial planes. Since planes and geometry have such a direct effect on color, he borrowed the aesthetic language of the broken plane from the Cubists and applied it to his paintings, creating a new abstract aesthetic approach that was part Divisionist and part Cubist. He most famously used this style in a series of paintings portraying what he believed was the ultimate symbol of the modern age: the Eiffel Tower.

Robert Delaunay - Eiffel Tower, 1911 (dated 1910 by the artist). Oil on canvas. 79 1/2 x 54 1/2 inches (202 x 138.4 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By gift. 37.463

Robert Delaunay - Eiffel Tower, 1911 (dated 1910 by the artist). Oil on canvas. 79 1/2 x 54 1/2 inches (202 x 138.4 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By gift. 37.463

Color and Contrast

One of the next discoveries Delaunay made had to do with contrast. He realized that colors could complement each other in a way that could create emotional reactions in the viewer’s mind. He began eliminating subject, depth, light and all other factors, focusing purely on color contrast for its own worth. He learned that different contrasting colors created different emotional effects. Some colors contrasted in a way that felt lighthearted or joyful. Others contrasted in a way that felt heavy or melancholy.

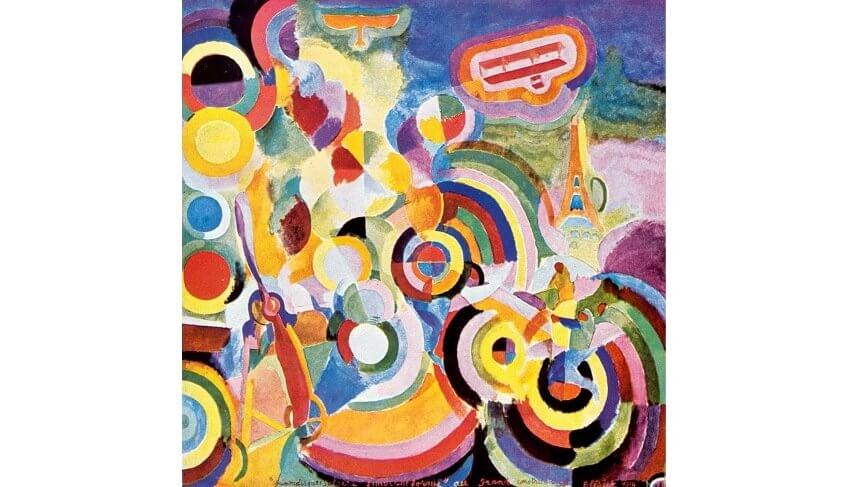

He also discovered that some colors when placed next to each other actually created a sense of movement. Viewers perceived them to jitter, vibrate, or even change hues the longer they looked at them. Delaunay called this sensation Simultaneity. In his 1914 painting Homage to Bleriot, he used the theory of Simultaneity in order to convey what he believed was the essential state of modernity, movement, represented almost entirely by color and purely abstracted form.

Robert Delaunay - Homage to Bleriot, 1914, Oil on canvas, 6 ft 4 1/2 x 4 ft 2 1/2 in. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Robert Delaunay - Homage to Bleriot, 1914, Oil on canvas, 6 ft 4 1/2 x 4 ft 2 1/2 in. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland

Robert Delaunay’s Legacy

History was important for Delaunay, and according to those who knew him he was quite aware of his place in it. He was particular fond of pointing out who, or what, was first. He wrote that, “The first paintings were simply a line encircling the shadow of a man made by the sun on the surface of the earth.” He praised the painter Seurat, founder of Pointillism, for first showing the importance of complementary colors. But he then went on to criticize Seurat for his incomplete accomplishment, stating that Pointillism was “only a technique.” Delaunay asserted that it was he himself who first used the theory of complementary colors to arrive at a pure expression of beauty.

Indeed, after reading Delaunay’s writings on color it’s plain that he is responsible for much original thinking about painting’s formal qualities. He and his wife Sonia are credited with inventing Orphism, one of the most influential abstract styles to emerge prior to World War I. But without taking anything away from Delaunay, having so much attention paid to color does beg a question: Can color truly be nature’s purest expression of reality? Can it be the only way to transfer beauty to our souls? It must be disheartening for blind person, or a colorblind person, to hear such news. Perhaps Delaunay’s thinking about color wasn’t the end of the story. Maybe what’s most important about his work is that he asked the questions many lovers of abstract art still ask today: What is reality? What is beauty? What is the best way to communicate them so that they connect with the human soul?

Featured Image: Robert Delaunay - Portrait de Jean Metzinger, 1906, Oil on canvas, 55 x 43 cm. Private collection

By Phillip Barcio