When Romare Bearden Went Abstract

Mar 25, 2020

If, like a lot of people, you missed out on seeing Abstract Romare Bearden at DC Moore Gallery in New York this winter thanks to the appearance of COVID-19, fear not: an even larger exhibition, titled Romare Bearden: Abstraction, will begin touring the United States in the fall (assuming the virus has run its course by then). Both of these exhibitions deserve praise for going beyond the widely known figurative works for which Bearden was known, and offering a deep dive into an underappreciated aspect of the career of one of the most influential, and introspective, artists of the 20th century—his large-scale, expressive abstractions. Bearden first came to prominence in the early part of the century as a social realist artist. His early works took as their subject matter the plight of Black Americans within a culture bound and determined to marginalize them because of the color of their skin. Considering the profound impact his figurative work had on the culture, it shocks some people today to learn that Bearden also delved deeply into the realm of abstraction. Yet, to Bearden, this was not truly a departure at all. He perceived all types of art—figurative, abstract, conceptual, whatever—as part of a unified effort humanity has always made to understand itself and its existence better. He thought of art as something that flows, but is distinct from real experience, and is thus not bound by rules that say it has to mirror what we actually see. “Art,” Bearden once said, “is artifice, or a creative undertaking, the primary function of which is to add to our existing conception of reality.” His abstract works elucidate this concept sublimely, and offer a fresh insight into the potential for abstraction to help us see ourselves and our world in new ways.

Metaphors and Myths

Bearden began his art career drawing illustrations and political cartoons for radical newspapers and magazines during the Great Depression. Even if we look beyond their shrewd, critical social content and look at them purely as studies of the bodies, faces and fashions of his fellow humans, we can see in those drawings what a critical eye for detail Bearden had. His particular gift was to simultaneously present scenes specific enough to be personal, yet general enough to be relatable to a broad segment of the public. He also used that eye for detail in his painting practice. His early paintings showed everyday Black Americans in familiar scenes, such as working in cotton fields and factories, or socializing in cities. Though instantly recognizable to his contemporaries, these paintings also possess a humanity that is still relatable today. Bearden also frequently brought religious scenes to life in his paintings, using them not so much as depictions of stories, per se, but as expressions of the timeless mythological gravitas of the human condition.

Romare Bearden - River Mist, 1962. Oil on unprimed linen, and oil, casein, and colored pencil on canvas, cut, torn, and mounted on painted board. 54 1/4 x 40 7/8 inches. DC Moore Gallery

Though his early style was somewhat modern, and even then hinted at an awareness of the communicative potential of abstraction, it was also somewhat like that of the many regionalist painters America was producing at the time. Bearden wanted more than for his work to be pigeonholed as regional, or even figurative. He wanted to endow his paintings with metaphor, to bridge the individual experience with a collective understanding. After finishing his Army service in World War II, he returned to Europe to visit the studios of European Modernists. When he returned to New York, he explored the techniques he learned from them, and also flirted with Abstract Expressionism and various other contemporary positions, in search of his authentic voice. Essential to his evolution was his belief in social activism, and his daily participation in the struggle for Civil Rights. At times, his artistic searching even seemed to come into conflict with his political beliefs. At one such point, Bearden famously stated, “The Negro artist must come to think of himself not primarily as a Negro artist, but as an artist.” He later challenged that statement himself, realizing the futility of any creative person removing personal circumstances and experiences from their work.

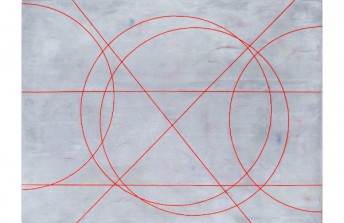

Romare Bearden - Old and New, 1961. Oil on canvas. 50 x 60 1/16 inches. DC Moore Gallery

Romare Bearden - Old and New, 1961. Oil on canvas. 50 x 60 1/16 inches. DC Moore Gallery

Collage as Social Action

Bearden arrived at what could be called pure abstraction around the late 1950s. About four years after Helen Frankenthaler started using the “soak-stain” technique, Bearden independently arrived at a similar method. Inspired by work he was doing with a Chinese calligrapher, he started diluting his oil paints and pouring them onto raw canvas, allowing them to mix together to create colorful, cosmic compositions. As with his figurative works, Bearden perceived these abstractions as expressions of something essential about the human condition. Some of his mediums did not mix, causing vivid separations to occur on the surface of a painting; other mediums swirled together to create something more complex and layered than what either could have achieved alone; some areas of his abstract canvases were left raw, acting as moments of revelation; some areas seem free and fluid, while others look tightly controlled and mapped out. Within these expressive realities, Bearden expressed the ideas, emotions, and associations of his everyday human existence.

Romare Bearden - White Mountain, c. 196. Oil and casein on canvas, cut and mounted on painted board with graphite. 50 x 34 3/4 inches. DC Moore Gallery

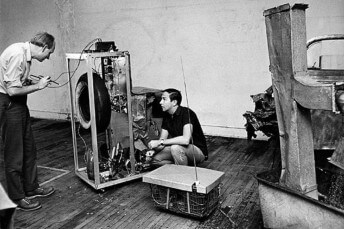

Some of his most distinctive abstract compositions make use of the collage technique, which Bearden began using around 1963. More than a year before the Canadian writer Marshall McLuhan coined the phrase “the medium is the message,” Bearden demonstrated a profound grasp of that same idea by demonstrating how the medium of collage expresses the message of collective action. His abstract collages do not only portray a unified composition of colors, shapes and textures—they also show how diverse elements can be combined to create something unified, powerful, and clear. Their cobbled together appearance and obvious artifice, in fact, “adds to our existing conception of reality” in a profound and beautiful way.

Romare Bearden: Abstraction, featuring a large selection of abstract collages and paintings by Bearden, will open at the University of Michigan Museum of Art in Ann Arbor, Michigan on 10 October 2020; at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Washington on 13 February 2021; and at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina on 15 October 2021.

Featured image: Romare Bearden - Feast, 1969. Collage of various papers on wood panel. 21 x 25 inches. DC Moore Gallery.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio