The Versatile Photographic Practice of Ryan Foerster

May 11, 2017

Conservation is one of the core ideas of photography. Capture a vision of reality. Do not waste time by letting it slip away. Conserve a fragment of the moment so it might be experienced after the moment is gone. The compulsion to conserve is partially what makes Ryan Foerster one of the most compelling artists of his generation. Foerster demonstrates photographic conservation in the usual sense, meaning he takes photographic images and shoots films of the real world, conserving images of reality for others to see later. But he also practices conservation in other ways. He conserves materials, finding new uses for the scraps left over from his projects. He conserves the relics of his community, picking up detritus as he moves around his adopted home of Brighton Beach, New York. He conserves energy, allowing the elements of nature and time to collaborate with him in his process. And he conserves judgment, never wasting it, instead waiting until later, much later, maybe never, before deeming anything a success or a failure. After all, judgment has no enduring value to an artist. As the work of Ryan Foerster demonstrates, what seems ruined may only be in a state of transition; what seems like a waste product may only be awaiting a new purpose; what seems like a disaster may be the start of something unexpected; and what looks hideous may only need to be seen in different light.

Ryan Foerster Reuses Manhattan

Ryan Foerster was born in 1983, in the former farming and industrial town of Newmarket, Ontario, on the outskirts of Toronto. His first artistic efforts revolved around the Toronto punk rock scene in the late 1990s. He published zines with his friends, and in the process learned about writing, photography, printing, journalism and all of the other aspects of analog media production. His zines gave him access to bands, which he sometimes interviewed in exchange for admission to their shows, and brought him into the orbit of a group of creative collaborators. The experience inspired him to become an artist. In particular, he felt driven toward one specific aspect of the creative process: photography.

In 2005, Foerster moved to New York City and enrolled in classes at the International Center for Photography (ICP). Located in the heart of Midtown Manhattan, ICP bills itself as a vital, cutting edge environment, one that leads the way in avant-garde photographic pedagogy. And it may be exactly that, but it was not the right place for Foerster. As he told BOMB Magazine in 2015, “I just wanted to make things and be in New York. So I dropped out.” Instead of academic credit, Foerster devoted himself to earning artistic credibility. He was nearly broke all the time and was in a constant state of confusion about his decision to make art in New York. But the scarcity of his lifestyle led directly to his sense that everything matters, both in survival and in art. Rather than using expensive cameras and new film he worked with whatever materials he could scrounge up, a supplies list that included the loose-ends of the film rolls of other artists, damaged photo paper, discarded printing plates, and innumerable found objects such as windows, mirrors, scrap metal, rocks, shells, and even slag, the left over byproduct of the metal smelting process.

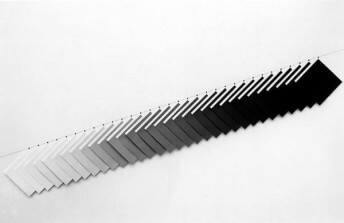

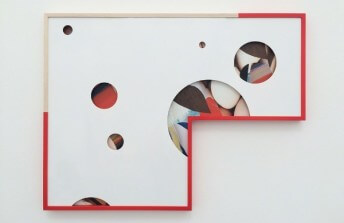

Ryan Foerster - Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, USA, 2014, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

Ryan Foerster - Installation view at C L E A R I N G, New York, USA, 2014, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

The Aesthetics of Evolution

At first, Foerster was dismayed by the harsh aesthetic qualities of the hand-me-down materials he was using. Damaged photo paper and film negatives do not result in pristine prints. But his dismay evaporated as he became more connected to the formal aesthetic qualities of the transitory state. Damaged paper has its own aesthetic position, and when it is allowed to express the inherent qualities it possesses it can lead to new discoveries and new ideas. Rather then fighting with the aesthetics of decay, Foerster embraced them as the aesthetics of rebirth. He began seeing all discarded and undervalued materials as simply materials that had outlived their intended use, but that possessed the potential to be given a new identity through artistic intervention.

The range of possibilities Foerster has since discovered for his found, inherited, and repurposed materials is vast. After hiring a printing company to print a zine on newsprint, he recovered the printing plates from the garbage and incorporated them into his work. After setting a cup of water down on a sheet of photo paper he noticed the way the water altered the color and texture of the paper and started experimenting with that process in his work. After Hurricane Sandy flooded his basement and moistened many of his photos, he was thus already prepared to embrace the aesthetic potential of water-damaged emulsion, and was able to salvage those damaged prints and redirect them into aesthetic phenomena that surpassed their original intent.

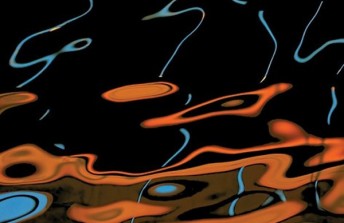

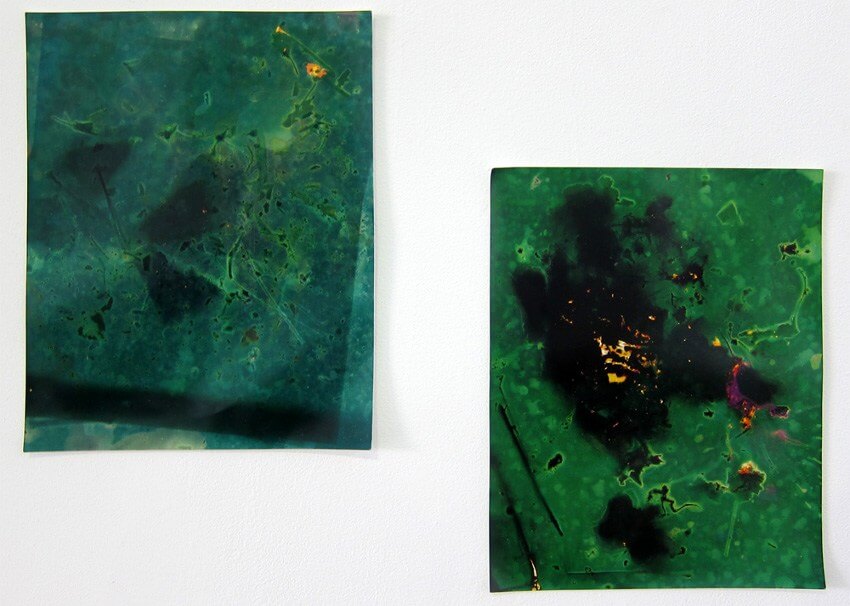

Ryan Foerster - Untitled Garden Print, 2014, Unique C-print, 61 x 51 cm, (Left) and Untitled Garden Print, 2014, Unique C-print, 61 x 51 cm, (Right), Photos by Gert Jan van Rooij, courtesy Upstream Gallery

Ryan Foerster - Untitled Garden Print, 2014, Unique C-print, 61 x 51 cm, (Left) and Untitled Garden Print, 2014, Unique C-print, 61 x 51 cm, (Right), Photos by Gert Jan van Rooij, courtesy Upstream Gallery

Natural Processes

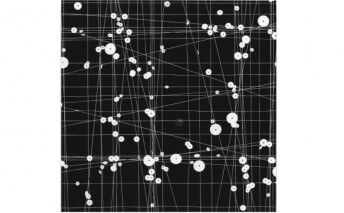

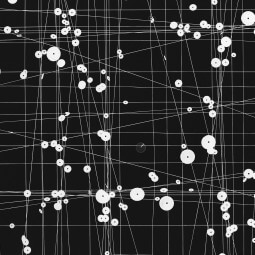

One of the most formative experiences Ryan Foerster had with the reuse of materials came about in 2009, when a photo of his was damaged in an exhibition at a gallery. Most artists would be devastated, angry, or at least eager to seek reparations, after such an event, but Foerster held true to his belief that accidents can be useful and materials can outlive their original intent: even if the material in question is an original artwork. Foerster set the damaged photograph outside on his roof and allowed rain to fall on it. The result was a new work he titled Universe/Night Swim. The image could easily be read as a picture of the night sky, full of distant stars and exploding galaxies, as seen through a telescope. But the white dots are in fact only damaged emulsion caused by falling rain.

In 2012, Foerster elaborated on this idea of allowing natural process to intervene in his work in a collaborative project he did with Shoot The Lobster gallery. For the project, Foerster took over an abandoned urban lot in Miami, Florida, and filled it with an outdoor installation of his works. The works were assembled on site in such a way that they blended in with the so-called natural environment. The aesthetic qualities of the materials Foerster used, such as scrap wood, metal, rocks, and old printing plates, spoke in perfect conversation with the visual language of abandoned urbanity. Once installed, Foerster left the work to be ravaged by whatever elements sought to interact with it, whether that be the weather, animals, or people passing by.

Ryan Foerster - Installation at C L E A R I N G, New York, USA, 2014, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

Ryan Foerster - Installation at C L E A R I N G, New York, USA, 2014, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

Relationship Advice

Ryan Foerster often compares his process to composting. Like someone gathering food scraps out of their garbage and spreading them in a backyard garden, he gathers up the waste products of society, mixes them in with the byproducts of his own activities then uses the mash to feed the germination of a new generation of ideas. Just like the crops once harvested on the bygone farms of his hometown, the so-called finished products of his process are only representatives of the next phase of another, much longer, ancient, never ending process. Formally, the work is abstract. Its language is one of vivid colors, apocalyptic textures, uncanny forms and haphazard compositions, balanced with occasional figurative elements that appear like ghosts, or memories interspersed among bursts of primal energy. But realistically, the work is never finished. It captures a moment in time, like a photograph, but the elements will never stop working on it, altering it, evolving it into something new.

Not even Foerster can ultimately say what his works will eventually become. Even as they are being installed he is still negotiating his understanding of them based on their relationships with each other and their surroundings. And somewhere in that fact lies the most important aspect of the work. It is about relationships. It expresses the relationship the artist has with materials. It interrogates the relationship culture has with consumption. It engages in passing relationships with natural processes. It investigates the relationship between the artist and the desire for control. Most compellingly, it invites viewers into new relationships with all of these elements. Of course, found art, recycled materials, and the idea of allowing the natural elements to collaborate in the creative process are nothing new. But Ryan Foerster engages with all of these ideas in a way that is undeniably contemporary. His work is humble in the sense that it admits that the ego of the artist is only one part of a larger event, and even sometimes relegates the artist to the role of editor. Such humility grants us as viewers permission to also not have all the answers, but to simply allow ourselves to be participants in something ongoing, something bigger than us, and something that may ultimately end up much different than it was intended, or than we ever imagined it would be.

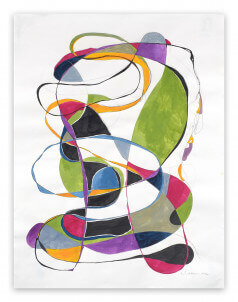

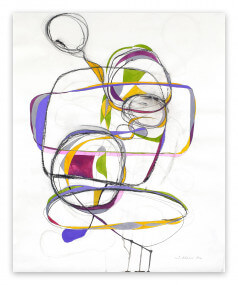

Ryan Foerster - Green Garden Prints, 2013, Unique chromogenic prints, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

Ryan Foerster - Green Garden Prints, 2013, Unique chromogenic prints, courtesy Cooper Cole Gallery

Featured image: Ryan Foerster - Untitled Garden Prints, 2014, Two unique C-prints, 61 x 51 cm each, Photo by Gert Jan van Rooij, courtesy Upstream Gallery

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Tenesh Webber

1963

(USA)Canadian

Richard Caldicott

1962

(UK)British

Seb Janiak

1966

(France)French

Paul Snell

1968

(Australia)Australian