Mystical and Metaphysical - The Art of Shirazeh Houshiary

Aug 21, 2017

It is not always a delight to think about the nature of existence: we are so obviously frail, and this life is so obviously temporary. But I, for one, nonetheless see it as a priority to confront the nature of what I am. Thankfully there are artists like Shirazeh Houshiary, who help me out by finding aesthetically interesting ways to confront the biggest questions, such as: what is real; what is imaginary; what does it mean to exist; what does it mean not to exist; and does existence ever truly end? Houshiary creates objects that, as a writer at the UMASS Amherst Fine Arts Center put it, “bear the tension between being and thought.” Her work is called mystical, a term that suggests mystery and hints that something spiritual is in play. And I would agree with that descriptor. The longer one stares at her works, the more theytake on the characteristics of ferrymen, entities with one foot in this world and one foot in the next, who are prepared to help you cross over to the other side. But the workHoushiary makes is also, quite often, called metaphysical. That is a term I am not as quick to embrace, although it is a source of fascination for me. But I am stuck in my own head asking, “How can something physical also be metaphysical?” Is not physics is the branch of human knowledge through which we quantify the observable, measurable universe? Are artworks not defined by their observable, measurable properties?The word metaphysics comes from the ancient Greek ta meta ta phusika, meaning the things after physics. It explicitly suggests there is more to our existence than whatever is observable or measurable. It refers to the unseen, the intangible, the ever changing, and the limitless. I sometimes think it is magical thinking to suggest an object, such as a painting, a sculpture or a video, can by metaphysical. But then again, perhaps not. There may be a limit to what we can know, whether we are studying the far reaches of space or the minute reaches of our own bodies and minds. Or maybe whatever is after physics is also part of physics, we just do not yet know how to see it, how to measure it, how to express it, or what it means. Regardless, it is a topic well worth delving deeper into, and one that is at the art of everything Shirazeh Houshiary makes.

Seek Revelation

The first work by Shirazeh Houshiary that I ever saw was a painting at the Tate called Veil. The piece attracted me because it seemed to be completely black. I tend to be drawn to monochromatic works because I like to get close to them to see what they are made of, and to try to guess how they were made. The complete lack of narrative or formal content allows me to appreciate other things, such as texture, glean, and finish. It also allows me to just really freak out on color. But the longer I looked at Veil, the more I realized that I was not looking at a monochromatic painting. Within the aesthetic arena of the painting there indeed gradually seemed to be some kind of content. A square emerged in the upper center of the picture, and within that square other forms emerged: other squares perhaps, a circle, or maybe a cross pattern. Depth began to manifest from the push-pull of the lightness and darkness. Soon I was pulled into something that was far more complex than I had first realized, or had hoped.

Veil was the perfect introduction to the work of Houshiary, because that work, at least for me, is entirely about perception. I had an existing agenda already in my mind when I approached the painting, which was to fetishize the surface qualities of a monochromatic work. I had my own tastes, my own opinions, and my own so-called sophistication, all of which longed to be validated. But without any resistance whatsoever, I willingly and pleasurably let all of that go. Contemplating the experience now, after the fact, I see the simple, and yet profound lesson I learned: it is possible that everything I think I know is wrong, or at the very least incomplete. Of course, the title, Veil, is the perfect reference to this lesson. A veil is something that only allows a person to see a partial view of the world. Ironically, the painting in this case was not the veil. It is what helped lift the veil, allowing me, the viewer, to see beyond what was visible before.

Avoid Exactitude

But despite the fact that Veil helped me, in my opinion, to see more and in theory know more, Houshiary has called that painting “a protest against knowing.” That way of describing it is apt, though, because it addresses the idea of mystery. It touches on my own questions about whether anything such as metaphysics can exist. It is statement of openness, and an admission that science is still grappling with the existence of the unknown. And that is something that is essential to what Houshiary is trying to achieve with her work. As she said in an interview with the Tate Modern, “What I’m trying to do is not be advertising. Advertising tells you exactly what it is. What art does, it has ambiguity, it leads you to discover. It has possibility. It is multidimensional. I want to see an art that...makes me think about my own evolution in the world...and my place in this space and time of this universe. When people give you fact in advertising, it basically kills your imagination.”

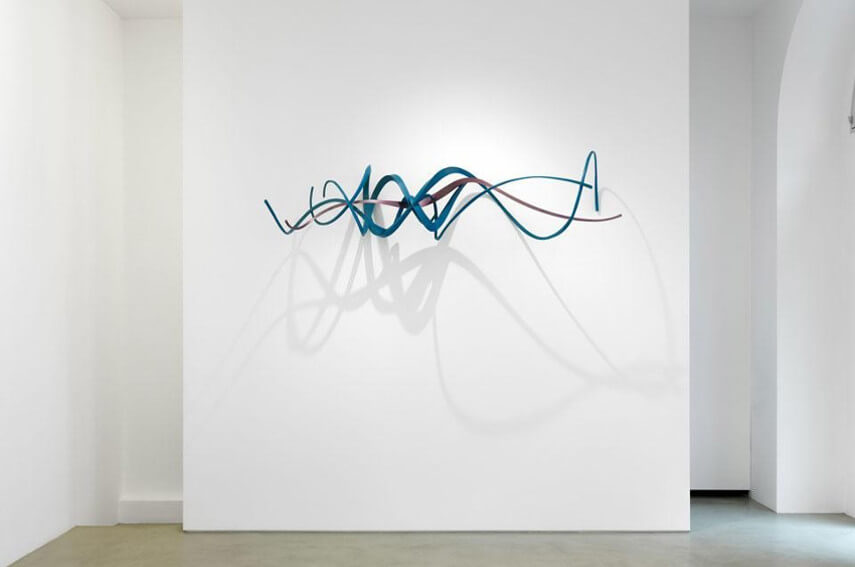

An excellent example of the multidimensional ambiguity of which Houshiary speaks is her 2011 sculpture Lacuna. This piece is designed to hang on a wall. As an object, it is an expression of line, movement and color. But when lights hit it, shadows expand dramatically outward in all directions. The resulting phenomenon recalls the simple, pared down, yet powerful gesture Richard Tuttle achieved when he first hung delicate wire pieces from the walls of galleries in the early 1970s. The presence of this physical thing is doubled, tripled, perhaps enlarged indefinitely by the reach of its ethereal, yet plainly visible shadow. And yet the colors are not extended into space, nor is the hardness. Some things must be essential to the nature of physical objects. Lacuna is part physics and part metaphysics. It is easily describable, yet not easily definable. It is three-dimensional, yet it changes with light, striving toward the fourth dimension: time. Its nature is determined as much by the materials from which it is composed as it is determined by the empty space within it and around it, and by the conditions of its environment.

Shirazeh Houshiary - Lacuna, 2011, cast stainless steel, 80 x 220 x 80 cm, © Shirazeh Houshiary

Shirazeh Houshiary - Lacuna, 2011, cast stainless steel, 80 x 220 x 80 cm, © Shirazeh Houshiary

Disintegration and Unification

One of the most common elements Houshiary incorporates into her work is breath. But perhaps it is too simple to call it just that. She is more interested in confronting the questions of what exactly breath is. Obviously, breath is just the name we give to the air that flows in and out of our lungs allowing us to stay alive. But breath is also representative of so much more than that. It is a process that begins with our beings inviting the outside universe in and then unifying temporarily with it, and ends with our beings disintegrating that union, expelling what is part of us outward, back into the abyss from whence it came. Breath is a rising and a falling, a shortening and a lengthening, a circular expression of the grand ultimate nature of all things that live and die.

Houshiary aesthetically manifests the process of breathing in her towers. Their solid elements are in themselves rigid and immovable, and yet the curvilinear forms demonstrate the inherent flexibility and fluctuation of all physical things. The fact that both states of existence—the solid and the fluid—exist simultaneously in one structure is what matters most. As Houshiary told Elizabeth Fullerton, a reporter for Reuters who covered her in an article for ARTNEWS in 2013, “It is as if the same object is constructed and collapsed simultaneously. The universe is in a process of disintegration, everything is in a state of erosion, and yet we try to stabilize it. This tension fascinates me and it’s at the core of my work.”

Shirazeh Houshiary - Stretch, 2011, Anodised Aluminium (Violet), Width 85, Length 85, Height 123.5 cm, © Shirazeh Houshiary and Lisson Gallery

Shirazeh Houshiary - Stretch, 2011, Anodised Aluminium (Violet), Width 85, Length 85, Height 123.5 cm, © Shirazeh Houshiary and Lisson Gallery

Featured image: Shirazeh Houshiary - Pencil, pigment on black Aquacryl on canvas, and aluminium, 47 1/5 × 47 1/5 in, 120 × 120 cm, © Shirazeh Houshiary and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio