Cubism of Sonia Delaunay and the Exploration of Color

Much could be, and has been written about the professional accomplishments of Sonia Delaunay. She was one of the most influential artists of the 20th Century. In her 20s, her visionary approach to abstraction led her to become one of the first Modernist artists. In her 30s, she transformed her studio practice into the manifestation of a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, demonstrating the Bauhaus ideal two years before the Bauhaus existed. She created a unique and influential body of paintings over the course of her life, working continuously until just shortly before her death at 94. And in addition to painting she also worked in fashion, theater, film, publishing and engaged in all manner of design activities. At age 79, she became only the second living artist ever to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre, and the first female artist to achieve that milestone. It could even easily be argued that Sonia Delaunay was the first artist to effectively turn her persona into a brand, in the contemporary context of the word. Except to focus exclusively on these external accomplishments would imply that it was her goal all along to achieve such things. But in fact, Delaunay intended no such thing. Her only goals were in earnest, to explore colour, form and composition, and to reveal to the rest of the world through her art the unknown essence of whatever it was that she sought within herself.

Becoming Sonia Delaunay

The story of the early life of Sonia Delaunay might resonate with any parent. How easy it is to create, or fail to seize an opportunity, and how the smallest change in circumstances can profoundly affect the chances of a child to succeed. Sonia Delaunay was born Sarah Ilinitchna Stern to a working class family in what is now Ukraine. Her opportunities in her hometown were severely limited, but she had a wealthy uncle and aunt in St. Petersburg named Henri and Anna Terk. The Terks could have no children of their own, and they asked to adopt Sarah from her struggling parents. Her mother initially resisted. But when Sarah was five years old her mother finally relented, and allowed her to move to St. Petersburg for good to live with her uncle and aunt.

Once she arrived in St. Petersburg, Sarah changed her name to Sonia Terk. Along with her new name came a new set of experiences and far more diverse possibilities. Life with her aunt and uncle included world travel, the finest education, and regular visits to museums and libraries. She was able to peruse books of art at home and to engage in intellectual discussions on a variety of topics. By age 16 she had developed an interest in becoming an artist. The Terks encouraged her interest, and at age 18 sent her to Germany to study art. Two years later, in 1905, she moved again, this time to Paris, the epicenter of avant-garde art in Europe.

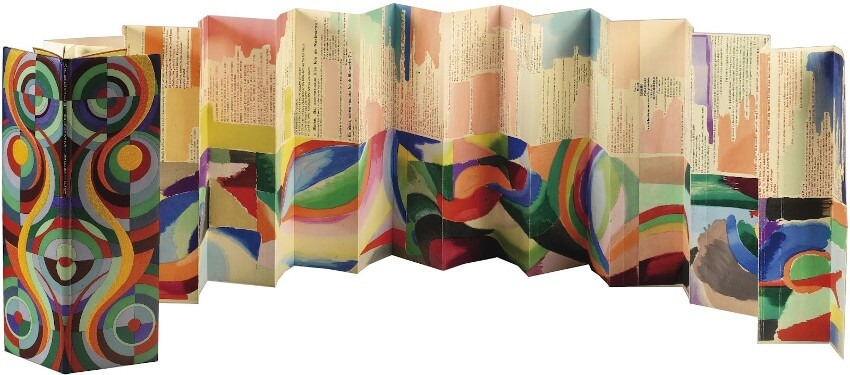

A book by the Modernist poet Blaise Cendrars, bound and illustrated by Sonia Delaunay in 1913

A book by the Modernist poet Blaise Cendrars, bound and illustrated by Sonia Delaunay in 1913

Discovering Colour

In Paris, Sonia Delaunay continued to study art in school, but the experience she had with her teachers was too academic and formal for her disposition. She found that she received much more inspiration in the galleries, which showed work by experimental European artists such as the Post-Impressionists. She had come to Paris at the perfect time. She found herself in the heart of the avant-garde community at the dawn of Cubism, when geometric planes were first adopted in an effort to convey four-dimensional reality. And she was there when the Futurist Manifesto was first printed in the French papers, bringing the idea of movement to the forefront of the artistic conversation. And the Fauvists, who were at the height of their influence when she arrived in the city, profoundly inspired her. She was viscerally moved by the way her eyes perceived, and her emotions experienced, the relationships between their brilliant and luminous colors.

The early paintings Sonia Delaunay was making after arriving in Paris explored many of the ideas of these other movements in a figurative way. But she was searching for something else. Specifically, she wanted a way of exploring the element of colour for its own merit. But she also wanted to be intuitive and free. She had little interest in the academic theories being exchanged by her contemporaries, which she thought were, “Too sophisticated. I’m closer to nature and to life,” she explained once, near the end of her life. “I was searching for something within myself and little by little it became abstract painting.”

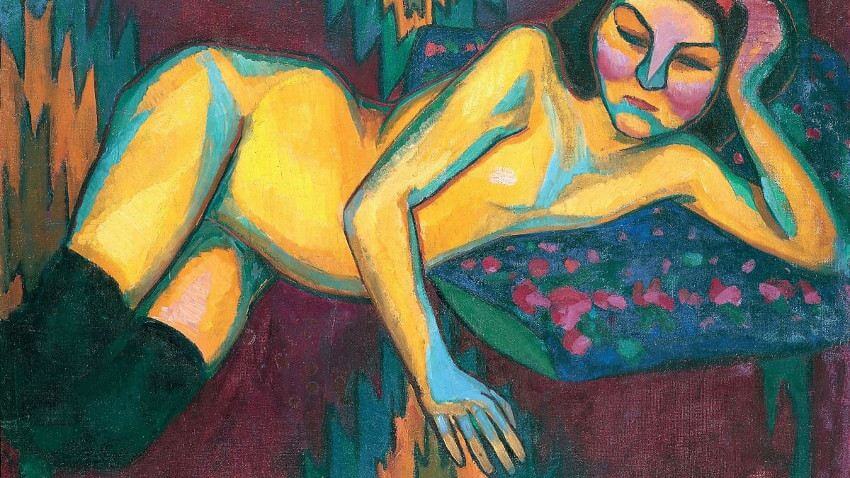

Sonia Delaunay - Yellow Nude, 1908. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, Nantes. © Pracusa 2014083

Sonia Delaunay - Yellow Nude, 1908. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, Nantes. © Pracusa 2014083

Finding Abstraction

The breakthrough that finally led Sonia Delaunay to fully embrace non-objective painting came in a most unexpected way. Like her departure from her hometown for St. Petersburg, it arose from a bold choice she made to create her own fate. When she had first arrived in Paris, she had befriended a gallery owner and writer named Wilhelm Uhde, who showed the leading avant-garde artists. She and he were kindred spirits, as she said, “both searching for something abstract.” They got married, not out of a romantic attraction, but because the arrangement provided practical benefits for both of them. For Sonia, it freed her from the pressure she was receiving from her birth mother to give up her career as an artist.

Then one night in the gallery less than a year later, Sonia met an opinionated, passionate young artist named Robert Delaunay. The two had an immediate connection and they fell in love. Sonia asked Uhde for a divorce, which he amicably granted, and the next year married Robert. When the two had their first child, Sonia handmade the baby a quilt using techniques based on Russian folk art traditions from her home. When the quilt was complete, she saw in it the inspiration she had been seeking. The shapes reminded her of Cubist planes, but the color relationships between the forms brought the entire composition to life. That quilt that Sonia Delaunay made from instinct for her child became the basis of all of her future abstract work.

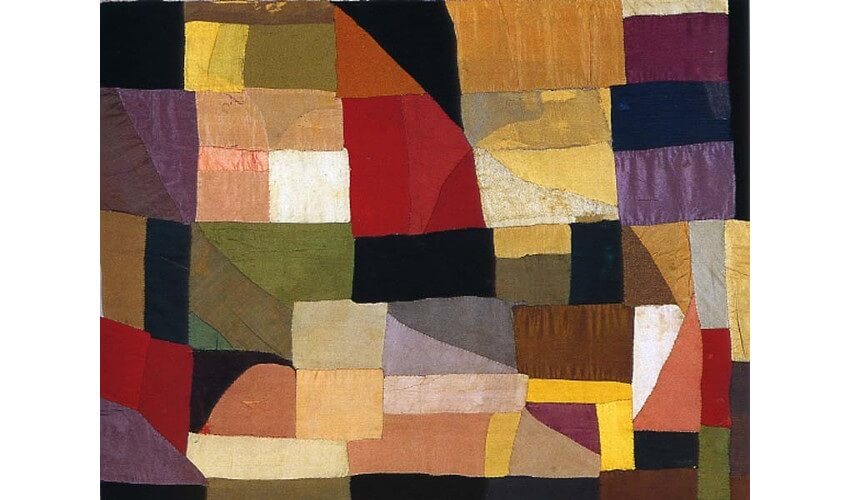

The quilt Sonia Delaunay made for her baby in 1911, now part of the collection at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, France

The quilt Sonia Delaunay made for her baby in 1911, now part of the collection at the National Museum of Modern Art in Paris, France

Orphic Cubism

In the evenings in Paris, Sonia Delaunay and her husband Robert Delaunay would walk together through the city and talk about art. On their walks they would marvel at the electric lights that were just then beginning to be installed. They would discuss the ways the colors of the city were affected by the synthetic light, and delight at the forms and patterns the light created. When they returned home from their walks, each would endeavor to capture on canvas their experience, using the language of abstract color and form inspired by the quilt Sonia had made.

They called their unique visual approach simultanéisme. The word was a reference to the relationship between colours and forms, and the simultaneous existence of multiple realities in their compositions. When Sonia and Robert exhibited these paintings, their friend, art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, dubbed their new style Orphic Cubism, or Orphism. Though the reference was never made perfectly clear, the term relates to the mythic Greek musician and poet Orpheus, whose legendary music was supposed to have had the ability to charm all creatures and things.

Sonia Delaunay - Rythme, 1938. Oil on canvas. 182 x 149 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Paris, France

Sonia Delaunay - Rythme, 1938. Oil on canvas. 182 x 149 cm. National Museum of Modern Art, Paris, France

The Poetry of Colours

Although the reference to Orpheus seems appropriate to the work of Sonia Delaunay, the comparison to Cubism is amiss. Cubism was as academic as it was aesthetic. While Robert Delaunay was an avid theorist and analyst, Sonia preferred to work intuitively and to put the emphasis on exploration and experimentation. About that dichotomy, she once said, “He talked, but I realized.” Even though Sonia used a language of forms similar to that of the Cubists, she had no intellectual goals in common with them. Her forms were only vessels for color. “If there are geometric forms,” she explained once, speaking at the Sorbonne, “it is because these simple and manageable elements have appeared suitable for the distribution of colors whose relations constitute the real object of our search.”

Sonia often compared painting to poetry. Sonia Delaunay saw herself as seeking out combinations of colors that could evoke a multitude of possible interpretations, and create simultaneous meanings. It was only natural for her to expand her artistic activities into the world of design since, as she experienced it, there was no separation between art and life. Whether her compositions resided on the side of a car, on a fur coat, on a costume for a play or on the surface of a canvas, she saw no difference. She believed that, “colors are words, their relations rhythms,” and that in whatever capacity she chose to bring them together they became, through her effort, “a completed poem.”

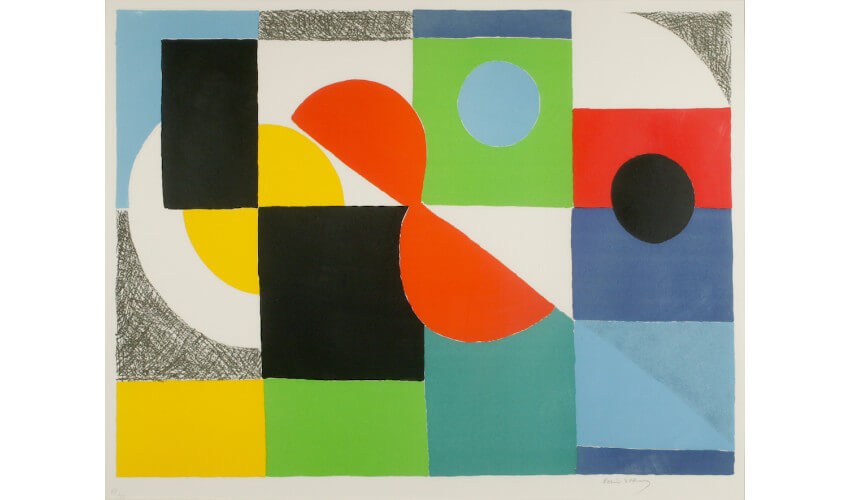

Sonia Delaunay - Grande Helice Rouge, ca. 1970. Lithograph. 72.5 x 88.5 cm. (28.5 x 34.8 in.)

Sonia Delaunay - Grande Helice Rouge, ca. 1970. Lithograph. 72.5 x 88.5 cm. (28.5 x 34.8 in.)

Featured image: Sonia Delaunay - Syncopated rhythm, so-called The Black Snake (detail), 1967

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio