How Sonya Rapoport Used Abstraction to Pioneer Computer Art

Sonya Rapoport is having a moment. Or more accurately, since the Berkeley, California-based artist passed away in 2015, the immense artistic legacy she left behind is having a moment. Following major group shows at SFMOMA and Hunter College Art Galleries in 2019, her work will be prominently featured this year in a solo presentation in the Frieze New York Spotlight Section, coinciding with Sonya Rapoport: Biorhythm, a partial retrospective at the San Jose Museum of Art from 7 February through 5 July 2020. Rapoport began her career as an abstract painter and sculptor. Her early work was celebrated in 1963 in what was ironically called a “mid-career” retrospective. Right after that exhibition Rapoport fundamentally changed her practice, becoming a pioneer of so-called Computer Art, a mode of expression she would continuously explore and redefine for 52 more years. Many curators and writers also like to call Rapoport one of the earliest makers of Internet Art, since she incorporated elements like personal data analyses and digital-social interactions in her installations as early as the 1970s. However, it may be more accurate to say that Rapoport herself was a sort of walking proto-Internet. Her mind was a virtual library of esoteric knowledge; she a connector who brought diverse experts together to collaborate on experimental aesthetic research; and her inspired projects cross pollinated individuals and organizations far beyond the realm of the art field. Part formalist, part shaman, part poet, part analyst, part hoarder, and part anarchist, Rapoport spawned one of the most complex artistic practices of the past century. Unraveling all of the symbols, meanings and layers in her work could take an art historian an entire lifetime, and a delightful lifetime it would be. Yet, in the rush to brand Rapoport with labels like Computer Artist and Internet Art pioneer, I wonder if we are overlooking the most essential aspect of her work: its humanity.

Digital Mudra

One of the first interactive art installations Rapoport made was Digital Mudra (1987). A mudra is a symbolic gesture or pose. The word mudra comes from Hindu, Jainist and Buddhist traditions, but every culture uses things like hand gestures as a shortcut to convey information and meaning. Digital Mudra exploited the universality of mudras by comparing drawings of ancient mudras with images of contemporary people physically acting out their feelings. Rapoport also invited other artists to compose poems based on mudra words, then re-interpreted those written poems into mudra poems that were displayed in the exhibition. Visitors to the gallery were then invited to participate by having their own gestures analyzed by a computer, which then printed out their associated mudra symbols and words, which could then be analyzed by a digitized version of Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, resulting in a personalized epigram suitable for hanging on the “mudra wall” as “temple writings.”

Sonya Rapoport - Biorhythm Calendar (detail), 1980. Multimedia collage on continuous feed computer printout vellum on found calendars 31.75 inches x 45.25 inches each. Courtesy Estate of Sonya Rapoport

Despite how seductive it is to say Digital Mudra was a computer installation, to me it seems more abstract than that. It seems more like an attempt to undermine our reliance on what can be known. Rapoport was playing with the idea that people want to believe in a power beyond their own intellect. Digital Mudra involved computers, but it also brought together mysticism, spiritual traditions, philosophy, poetry and art. Most importantly, it created a social situation in which people were encouraged to participate because of the participation of others—everyone else is coming up with their mudra words, hearing the wisdom of the sage, and hanging their mystic epigrams on the temple walls, so why not join in? No question, this installation sounds a lot like an early social media meme quiz, but more than anything else I see it as an acknowledgment that our digital overlords are no different than all of the other overlords that came before, and will come after.

Sonya Rapoport - Biorhythm Calendar (detail), 1980. Multimedia collage on continuous feed computer printout vellum on found calendars 31.75 inches x 45.25 inches each. Courtesy Estate of Sonya Rapoport

All Is One

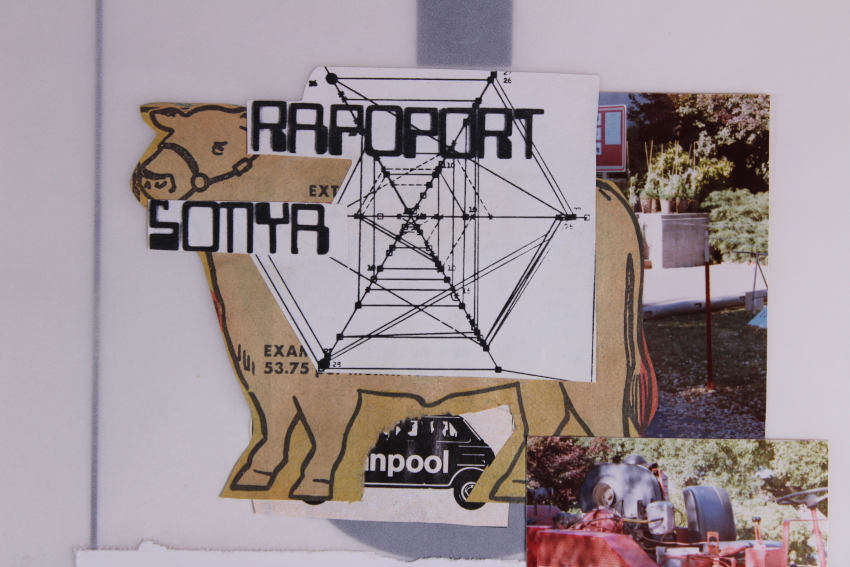

Collage was another favorite medium for Rapoport. She famously found a stack of survey maps in an old desk she bought, then used them as the background for intricate collage works, expanding their analytical context by infusing them with personal images and clippings. Later, she found reams of computer printouts in the garbage on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. She knitted the sheets together with yarn then used them as the basis for a series of works that mined her own vast wealth of feelings, dreams and influences. These works were not about computers, per se. They were more like abstract visual reactions to concrete visual proposals. As Rapoport said at the time, “my work is an aesthetic response triggered by scientific data.” Nonetheless, like someone going on an Internet deep-dive with hundreds of search tabs open at the same time, these “computer collages” overflow with innumerable interrelated snippets of whatever Rapoport was thinking about at the time. In addition to recognizable images and words, they are filled with formalist abstract imagery as well as references to her own personal “Nu Shu” language—a personal, symbolic, female script—culminating in works that are confident, strong, feminist, poetic, mysterious and endlessly intriguing.

Sonya Rapoport - Biorhythm Calendar (detail), 1980. Multimedia collage on continuous feed computer printout vellum on found calendars 31.75 inches x 45.25 inches each. Courtesy Estate of Sonya Rapoport

In the hopes that viewers would look deeper into her works, Rapoport always eagerly shared the extensive records she kept noting all of the references that inspired her. As countless new viewers are now being given the chance to encounter her legacy for the first time at art fairs and museum exhibitions, I hope curators will also take extra care to communicate that intent. One of the more annoying aspects of the digital age is that art viewers claim the entitlement to look at art quickly and superficially then swipe to the next image. Rapoport was no fan of that trend, nor of the dehumanizing limits it imposes on art and its makers. As this prescient artist finally receives her due, I encourage viewers to scratch beneath the surface of her work, and I encourage curators and writers to stop calling Rapoport a computer artist or an Internet artist—Rapoport was an artist who used technology to remind us of the innumerable ways we are still human.

Featured image: Sonya Rapoport - Koch II, 1972–74. Spray acrylic and graphite on canvas; 72 x 96 inches. Estate of Sonya Rapoport.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio