In Memory of Trevor Bell, A Look Back at the St Ives School of Painting

Nov 17, 2017

The passing of the great British painter Trevor Bell is being mourned as the end of an era. Bell is widely regarded as the last of the St. Ives School Modernists. The town of St. Ives is a historic fishing village in Cornwall, a peninsular county on the southwestern coast of England. Its rolling hills, rocky shores, quaint homes, sandy beaches and clear waters have attracted rugged dreamers at least as far back as 1312 when The Sloop Inn, the first local pub, opened for business. In addition to good surfing and excellent fishing, there has always been something extraordinary about the light in St. Ives. That is what began attracting painters to the area in the 1800s, when Impressionism and plein air painting were the rage. And in 1877, when the Great Western Railway extended to St. Ives, it became an even simple matter to travel there, so many more artists started to come. They painted replications of the cliffs, the sea, the boats, the village, and the hard working villagers bathed in that mysterious, glowing, St. Ives light. But when people in the art world talk about the St. Ives School, they are not referring to those early arrivals. Nor are they referring to the actual St. Ives School of Painting, the brick and mortar art school in the town. Rather, they are referring to a time in the mid-20th Century, when, for a couple of decades, this sleepy fishing village of St. Ives joined Paris, New York, and the other world capitals to become a global epicenter of Modern and abstract art.

The St. Ives School of Painting

Since the beginning of civilization, art and religion seem to have gone hand in hand. It is no different in St. Ives. But the connection between art and the church in St. Ives is not exactly what one might expect. The connection revolves around a gothic chapel begun in 1904, but never completed. The chapel was intended to support the Anglican community of St. Ives. But the space, which was built to accommodate more than 300 parishioners, proved far too large and grandiose for the fewer than 100 practicing Anglicans in the community. Soon after the church was begun, the supply of a small type of herring known as a pilchard, one of the key targets of St. Ives fishermen, dried up, causing an economic crash in the area. Just a few years after the pilchard collapse, World War I broke out. Within the next couple of decades the church gradually became neglected, and nearly abandoned.

But the seemingly doomed church was yet to have its heyday, thanks to an officer who fought on the front lines in World War I and who happened to also be an artist. Robert Borlase Smith was born in Kingsbridge, Devon, another southern, British, seaside community about 100 miles from St. Ives. He served in the Artists Rifles, an honored British regimen, in the war. After the war, he moved to St. Ives with his wife and dedicated himself to painting. His dramatic, figurative paintings of the crashing St. Ives surf established his reputation as a leading landscape artist in the 1920s. He and the other painters who were working in St. Ives at the time developed such a strong reputation that the area became internationally known as an artist colony. In response to its fame, Smith opened the St. Ives School of Painting in 1938, “To assist the many resident and visiting students in attaining the requisite proficiency to enable them to express themselves adequately in various mediums; especially to enable them to combine their studies in landscape with figure and portrait work, carried on simultaneously.”

Robert Borlase Smart - Morning Light St Ives, © Royal Institution of Cornwall

Robert Borlase Smart - Morning Light St Ives, © Royal Institution of Cornwall

The St. Ives Society of Artists

About ten years before opening the school of painting, Smith and several other figurative artists formed an official group that began exhibiting work together. They called themselves the St. Ives Society of Artists. They were staunchly traditional, espousing realistic painting and classical technique. And it was their academic point of view that dominated the classes at the St. Ives School of Painting, giving rise to a new generation of landscape painters who would even further cement the reputation the town had as a beautiful, light-filled, seaside artistic paradise. But the St. Ives Society of Artists had no official gallery to call their own. So in 1945, after World War II ended, Smith and his cohorts acquired that neglected, crumbling, gothic Anglican church and turned it into a gallery in which the St. Ives Society of Artist and the students from their school could exhibit their work.

Around that same time period, another type of artist starting arriving in St. Ives—Modernists who were more interested in abstraction than still lifes, portraits, and landscapes. Headed by British painter Ben Nicholson, British sculptor Barbara Hepworth, Russian sculptor and kinetic artist Naum Gabo, and Cornish abstract painter Peter Lanyon, these new arrivals to St. Ives signified a dramatic shift away from the local aesthetic traditions. The traditionalists did not mind at first. They embraced these painters in their school and even offered them the crypt of their church as a gallery space. But rapidly the newcomers sensed an innate prejudice against Modernist ideas, and especially against the validity of abstract art. In response to these biases, they started calling themselves The Crypt Group after their gallery space. Then in 1948, they completely separated themselves from the St. Ives Society of Artists, calling themselves instead the Penworth Society of Art. As a final gesture to set themselves apart, the Penworth artists named the art critic Herbert Read, a staunch and well-respected advocate of Modernism, as their president.

Barbara Hepworth - Large and Small Form, 1934, White alabaster, 9 4/5 × 17 7/10 × 9 2/5 in, 25 × 45 × 24 cm, ©Bowness

Barbara Hepworth - Large and Small Form, 1934, White alabaster, 9 4/5 × 17 7/10 × 9 2/5 in, 25 × 45 × 24 cm, ©Bowness

Enter Trevor Bell

Despite the drama that developed between the two opposing schools of arts in St. Ives, not all artists remained hardened in their thinking. One of the most famous turncoats was Terry Frost, who exhibited with the St. Ives Society for three years before switching sides in 1950 to join the Penworth Society. Frost would eventually go on to become one of the most famous and beloved British abstract artists of the 20th Century. And it was Frost who first recommended to Trevor Bell that he move to St. Ives. Bell graduated from the Leeds School of Art in 1952, and encouraged by Frost moved to St. Ives in 1955. Bell excelled there, earning his first solo exhibition in London in 1958, and winning the prize for painting at the inaugural Paris Biennale in 1959.

But he only stayed around St. Ives for about five years, leaving in 1960 to take an academic position back in his hometown, at the University of Leeds. Then in 1976, he moved to the United States to take a position teaching painting in the Masters department at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. But the legacy of color, light, and innovation that defined the St. Ives School remained always part of his work. That legacy expressed itself in the iconic large, colorful, abstract shaped canvases for which he is now mostly known. And despite staying away for as long as he did, Bell did eventually return to the St. ives area. He moved back in 1996, and maintained close ties to the community of artists and gallerists there until he died.

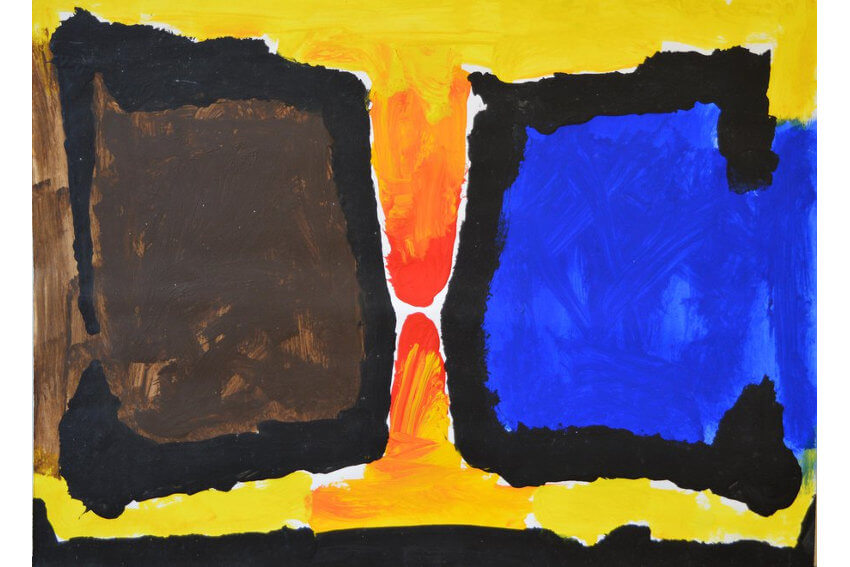

Trevor Bell - Meeting, 1980, Acrylic on paper, 22 x 30 in, © Waterhouse & Dodd, New York and London and the artist

Trevor Bell - Meeting, 1980, Acrylic on paper, 22 x 30 in, © Waterhouse & Dodd, New York and London and the artist

The St. Ives School Legacy

The accomplishments of St. Ives School abstract artists like Trevor Bell, Barbara Hepworth, Terry Frost, Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson have become so legendary over the years that in 1993, the Tate opened up a St. Ives location overlooking Porthmeor Beach, the popular local surfing destination. Tate St. Ives is dedicated to preserving the legacy of St. Ives Modernism. And in addition to running its own gallery, the Tate St. Ives is also the custodian of the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Gardens. When Hepworth died, she left instructions that her work should be shared freely with the public. The Tate maintains the grounds and facilities at the lush, spacious home and studio where Hepworth used to live and work.

Acting as both a collecting and exhibiting institution, the Tate St. Ives showcases work from the most renowned period of St. Ives Modernism, from the 1940s through the 1960s. But it also explores related works and artists, including those representing other generations including up to the present moment. Though the term St. Ives School is most often used to reference something in the past, this rugged, seaside town is still as active as ever as an artist colony, and is today as vibrant as it has ever been. Though Trevor Bell might have been the last of the St. Ives Modernists, his legacy and that of his contemporaries lives on in this special place, which was once the center of British abstract art, and may yet be again one day.

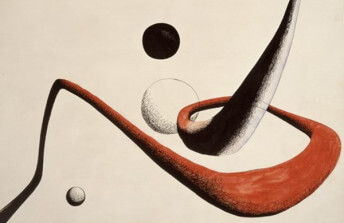

Trevor Bell - Notched forms with a wedge, 1984, Acrylic on paper, 22 x 30 in, © Waterhouse & Dodd, New York and London and the artist

Trevor Bell - Notched forms with a wedge, 1984, Acrylic on paper, 22 x 30 in, © Waterhouse & Dodd, New York and London and the artist

Featured image: Trevor Bell - Blue Radial, 1985, Acrylic on canvas, 96 x 140 in, © Waterhouse & Dodd, New York and London and the artist

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio