Why the Grid Paintings of Stanley Whitney Matter

Feb 22, 2017

The recent paintings by American abstract painter Stanley Whitney have a distinct grid-like quality. They are architectonic stacks of colors, evocative of Neo-Plasticist television color bars. And his recent drawings lay even barer his attraction to the grid, comprising simple compositions of thick black lines resembling a rudimentary checkerboard or fishnet. But Whitney was not always a grid painter. The grid was something toward which it took him decades to gravitate. In fact, when looking over the past five decades worth of his paintings one cannot help but attach a sort of progressive narrative to the work, one that has extended far beyond its origins, and become both more simple and more profound along the way. This is ironic because Whitney once said on the Modern Art News Podcast that the reason he adopted an abstract visual language was because, “I didn’t really want to be a storyteller.” But his aesthetic evolution does tell a story. It is not a typical, heroic, beginning-middle-end type of story. It is rather more like a chronology, or a series of news reports from the front lines of an ongoing battle. That battle, which Stanley Whitney has been waging since even before turning to abstraction in the late 1960s, is with the mediums of painting and drawing, and their role in the expression of color and space.

A Colorful Youth

It is no surprise that Stanley Whitney has become known for his examination of color. Now in his 70s, he tells a lovely story about being a ten-year old child attending his first painting class at a neighborhood school in his hometown of Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. The teacher instructed the kids in the class to paint self-portraits. While the other students made attempts to capture their various realistic visages, Whitney felt drawn more to color than to representational subject matter.

Instead of trying to mix a color palette that related to his actual appearance, he made a self-portrait that included every color he could come up with. Whitney says that the teacher liked the painting, but his parents did not understand it. They never sent him back to the class. But that did not stop Whitney from being drawn to the possibilities of painting and of color. In fact, it is no stretch to say that ever since that day as a ten-year old in his first painting class, Stanley Whitney has remained committed to searching for the ideal way to make color his subject.

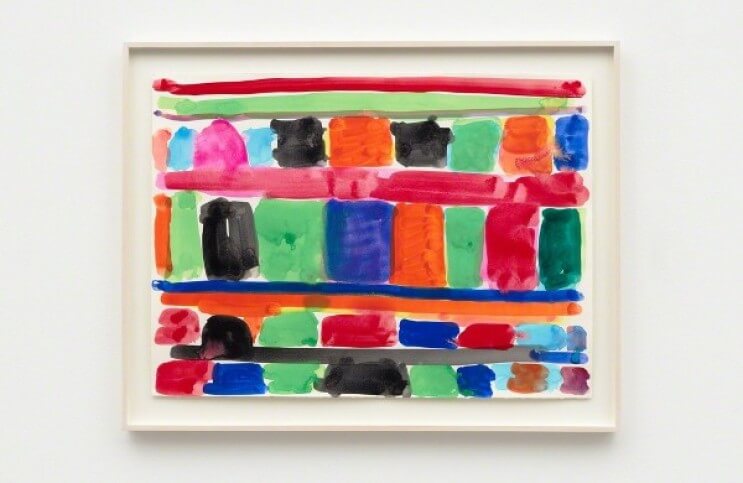

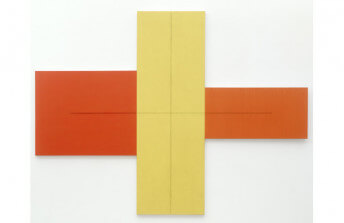

Stanley Whitney - Champagne and Lion, 2010, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Stanley Whitney - Champagne and Lion, 2010, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Finding Space

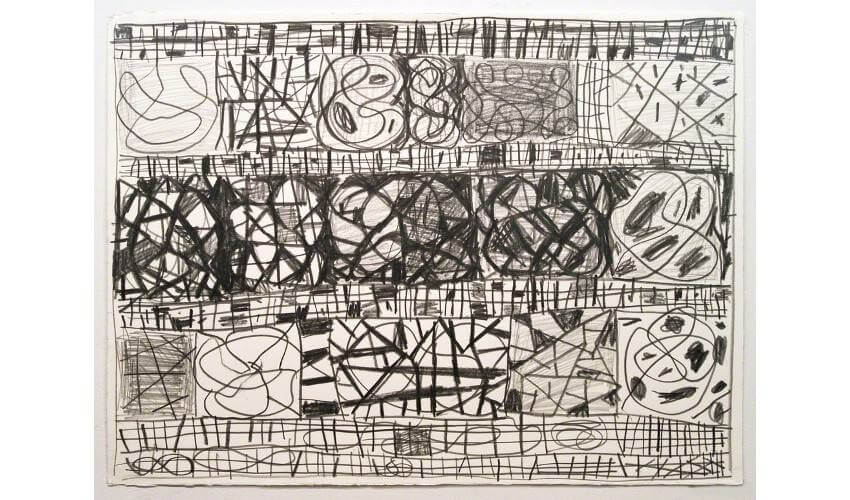

In addition to his attraction to color, Stanley Whitney was also drawn as a youth to the process of drawing. His black and white drawings seemed at first to be unrelated to his love of color, but there was a subtle connection between the two that it took him many years to realize. The connection has something to do with space. When making his black and white drawings, he found that the distribution of space could occur in innumerable ways as the lines negotiate their relationship to the white space in the composition. As he became more adept at painting, however, he was baffled by how to achieve that same negotiation of space with color.

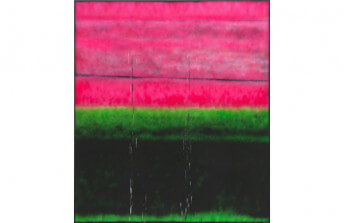

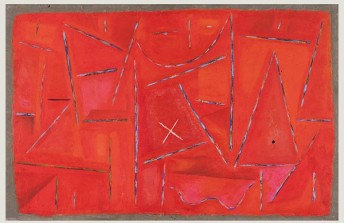

In his early figurative works, the colors feel claustrophobic and tight. In his first forays into abstraction, which were riffs on Color Field Painting with added gestural markings, the colors feel too loose. He said, “I want a lot of air in the work. I want a lot of space in the work.” But he seemed bogged down by exactly how to create airiness on top of the space of the canvas. His revelation came in the 1970s on a trip to the Mediterranean. While visiting Egypt and Rome he saw the answer in architecture and light. The Ancient architecture expressed structure, control, and the democratic potential of stacked elements. The Mediterranean shadows and light showed him that color and light are the same, and that cool and hot colors, like cool and hot light, express space. That unlocked a mystery of painting that, as he says, “The air and the space could be in the color, not that the color was on the space.”

Stanley Whitney - Untitled, 2013, graphite on paper, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Stanley Whitney - Untitled, 2013, graphite on paper, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

A Methodical Process

“That was the beginning of things coming together,” Whitney says. From that point forward he has been evolving slowly toward the grid paintings he makes today. He has explored using graffiti-like gestures to determine how color can be expressed by line, similar to the work of Mondrian. He has examined ways of approaching the grid, from stacked shapes to rows of dots and bands of colors. He knew he wanted a skeletal framework to contain his colors in an equitable way, but that he also did not want the rule of the grid to force his pieces in a particular direction. He wanted to find the perfect mix of structure and freedom, like Jazz.

Stanley Whitney - Lush Life, 2014, oil on linen, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Stanley Whitney - Lush Life, 2014, oil on linen, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

The mature grid works that Stanley Whitney now makes are pure and stable. They even seem at first to lack some of the grit and angst that made his earlier efforts feel so alive. But upon closer examination the painterly marks of the human hand are evident, and the complexity of the compositions reveal the depth with which Whitney still wrestles with his conundrum. He has found a way to make color his subject. He has discovered the secret that color and light are the same, and are both manifestations of space. And through these discoveries, he has made a body of work that is rich and undeniably full of meaning. But despite his discoveries, he has remained on the edge of the razor, never revealing, or perhaps never knowing or caring to know, precisely what that meaning is.

Stanley Whitney - Manhattan, 2015, oil on canvas, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Stanley Whitney - Manhattan, 2015, oil on canvas, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

Featured image: Stanley Whitney - Untitled, 2016, oil on linen, photo credits of Galerie Nordenhake

All images © the artist and Galerie Nordenhake;

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio