Synthetic Cubism Explained - Planes, Shapes and Vantage Points

Pablo Picasso, the father of Cubism, was famous for his eagerness to evolve. After inventing Analytic Cubism in 1907, he easily could have just kept painting in that style for decades and still gotten rich and famous. But instead he kept experimenting, helping invent what became known as Synthetic Cubism in 1911 by adding to Analytic Cubism an expanded color palette, new textures, simpler shapes, new materials and by simplifying the use of viewpoint and plane. From the time of its invention until around 1920, Synthetic Cubism was considered the height of the avant-garde. It expanded the range of ways painters could explore reality and contributed to the rise of the Dadaists, the Surrealists, and even Pop Art.

Synthetic Cubism in 200 Words

Synthetic Cubism resulted from a departure from those very techniques, in an attempt to create something even more real. Picasso, Braque and the painter Juan Gris added a vibrant range of colors back into their works, reintroduced depth, and diminished the number of simultaneous perspectives and planes in their imagery. Most importantly, in order to give the ultimate sense of reality to their paintings, they started adding paper, cloth, newsprint, text, and even sand and dirt to their works, attempting to bring a total sense of their subject’s essence into play.

Pablo Picasso - Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912, Oil on oil-cloth over canvas edged with rope, 29 × 37 cm, Musée National Picasso, Paris, © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

New Materials and Techniques

In 1912, Picasso created the work of art that’s considered to be the first example of collage, and a defining example of Synthetic Cubism: Still Life with Chair-Caning. The work is a Cubist representation of a café table with a selection of food items, a newspaper and a drink. In addition to traditional mediums, Picasso added to the surface of the painting a section of the wicker chair-caning that was traditionally found on café chairs. This seemingly trivial addition had tremendous consequences for Modern Art. Rather than painting a chair, part of a chair was actually put onto the painting. Rather than showing something from multiple perspectives in order for it to seem real, Picasso just put the actual thing, or at least part of it, directly onto the work.

Picasso also added text to this piece, writing the letters “JOU” across part of the surface. This word “Jou” literally could be translated as “game” in French, a fact which has contributed to the sense many people have that Picasso intended Synthetic Cubism to add a sense of frivolity back into art after the academic seriousness of Analytic Cubism. However, “JOU” could also easily have been intended as the first part of the French term for daily newspaper, or journal, a reference to the fragment of newspaper seen in the picture.

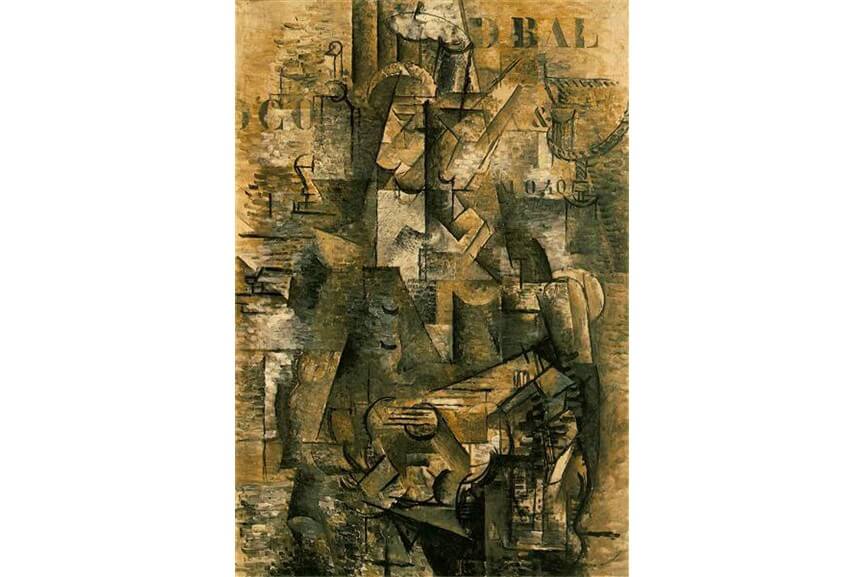

Though he achieved a first by adding that bit of chair-caning to his piece, Picasso wasn’t the first Cubist to add text to a painting. In 1911, Georges Braque had created a work called The Portuguese, which was the first Cubist work to introduce lettering. Evident in both Picasso’s first collage and Braque’s first textual piece is a shift away from the serious and overly complex nature of some of their later Analytic Cubist works. There’s a whimsical simplicity to the imagery on these artworks. The perspectives are simplified and the images are becoming almost playful, similar to the anthropomorphic images in advertising pictures.

Georges Braques - The Portuguese, 1911, Oil on canvas, 116.7 × 81.5 cm, Musée National Picasso, Paris, © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

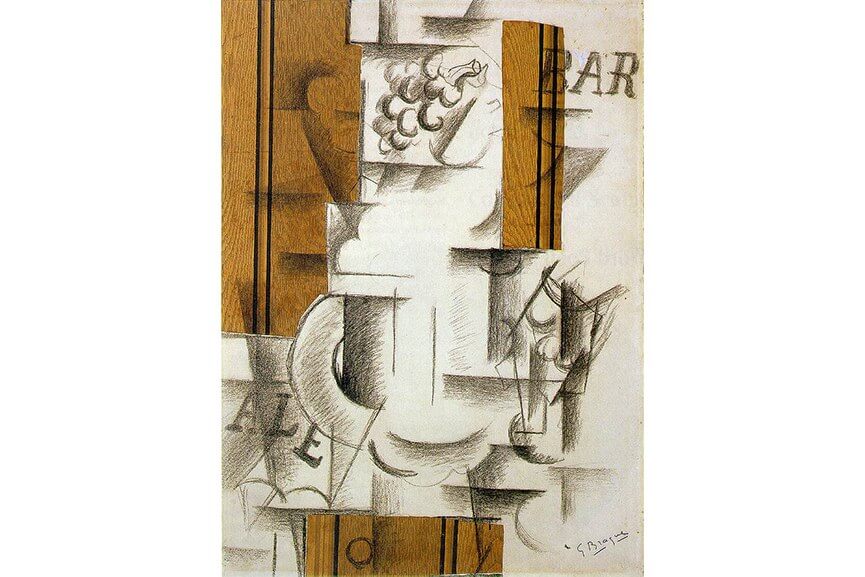

In 1912, Braque would break new ground at least two more times. That year he became the first Cubist painter to add sand to a painting in order to add levels of texture and depth to the work, and he also became the first to incorporate the technique known as papier colles, which refers to the pasting of cutout pieces of paper onto a surface. Both of these techniques were used in his work titled Fruit Dish and Glass. In this painting he applied cut out pieces of wallpaper directly to the surface and then shaded the piece using paint filled with sand, adding depth and texture to the image.

Braque also included text in this piece, using the clearly defined and easily readable words “Ale” and “Bar.” These words challenge to the lines separating advertising imagery and so-called high art. The combination of all three of these techniques would eventually prove to be a major influence on the Dadaists, who relied heavily on collage and text to confuse and obfuscate the apparent meanings in their works and to challenge Bourgeois notions of art.

Georges Braque - Fruit Dish and Glass, 1912, 62.9 × 45.7 cm, © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Planes, Shapes, Vantage Points and Colors

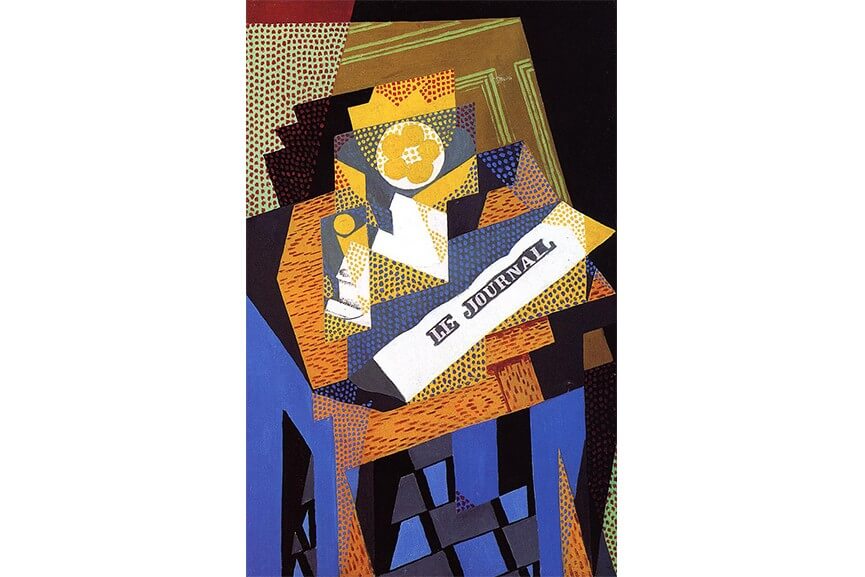

The artist most responsible for bringing vibrant colors into Synthetic Cubism was the Spanish Cubist painter Juan Gris. Gris also utilized a substantially simplified visual language that superbly demonstrates the reduced number of vantage points and the simplified use of forms and planes that defines Synthetic Cubism. In Gris’ work Newspaper and Fruit Dish, we see all of these elements in play. We can also see in this same painting many of the reasons that Synthetic Cubism is often seen as the pre-curser to Pop Art.

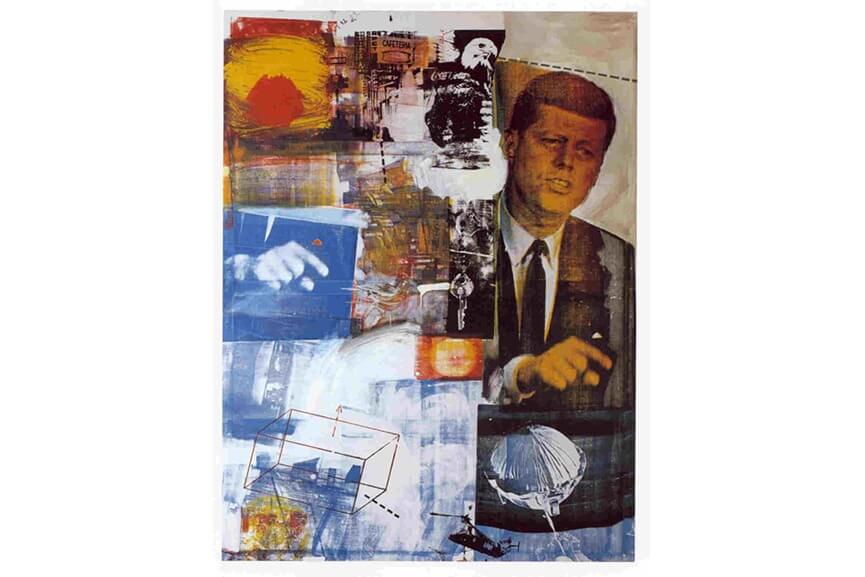

It’s not only that the Synthetic Cubists played with notions of the blurred line between low and high art, and art and advertising. This painting also amazingly evokes the Ben-Day dots of Roy Lichtenstein, and appears to almost identically foreshadow the repetition, image placement and color palette of Robert Rauschenberg’s buffalo II.

Robert Rauschenberg - Buffalo II, 1964, Oil and silkscreen ink on canvas. 96 x 72 in (243.8 x 183.8 cm). © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

The earlier Analytical Cubist paintings had incorporated so many different points of view that the complexity of the images became almost impossible to unravel. Their subject matter seemed abstracted to the point of being unrecognizable: each point of view was represented by separate geometric shapes on a separate plane and each plane seemed stacked atop the others and then flattened again. And the geometric shapes utilized in Analytical Cubist paintings seemed almost transparent at times. They were painted in a way that demonstrated speed, vibration and movement. They represented different times of day, different lighting and different viewpoints.

Juan Gris - Newspaper and Fruit Dish, 1916, Oil on canvas. 93.5 x 61 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

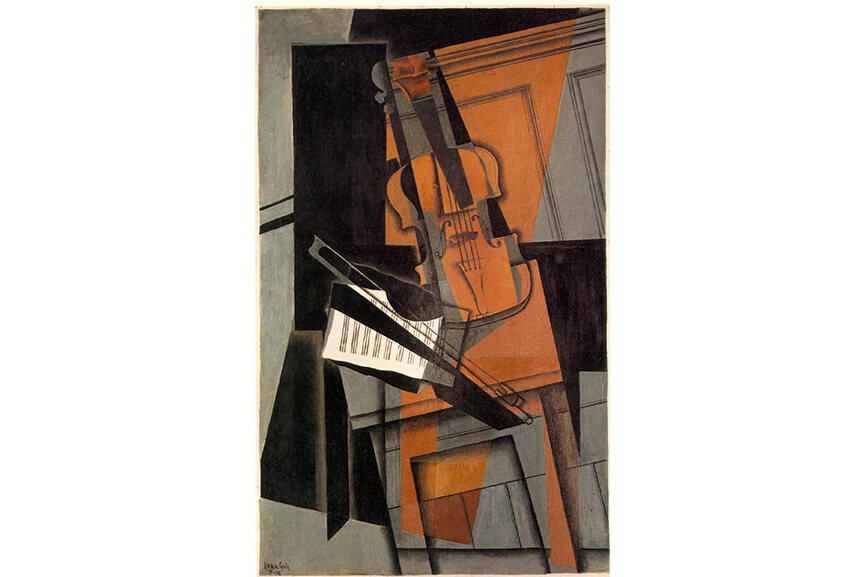

By adding a vibrant color palette back into Cubist pictures, Juan Gris gave the style a sense of playfulness and excitement that was lacking from those earlier Cubist works. And Gris’ simplified visual vocabulary presented the notion that Cubism could accomplish its goals in a straightforward, simplified, and aesthetically pleasing way. In Gris’ painting The Violin, he accomplishes the absolute bare minimum number of vantage points, shapes and planes in order to still be considered a Cubist work. The resulting image seems more like an example of the suggestion of Cubism than the rigorous definition of it.

Juan Gris - The Violin, 1916, Oil on three-ply panel, 116.5 x 73 cm, Kunstmuseum, Basel

Synthetic: Another Word For Fake?

By adding writing and bits and pieces of everyday objects into their paintings, Picasso, Braque and Gris were striving to connect with an enlarged sense of the realness of their subjects. But by adding those artificial elements to their works they were also creating something that was patently unreal, and unlike any of the Cubist works of art that came before. Sometimes they even painted forms that looked like collage, intermingling mimicked collage elements with real collage elements in the same work. This new style was named Synthetic Cubism precisely for that reason, because of the artificial nature of the techniques being used relative to the seriousness of the Cubist work that had come before.

Synthetic Cubism was more symbolic than Analytical Cubism. It did not strive to achieve a heightened view of four-dimensional reality. Rather it strived to achieve a hint at reality, but in a distorted way. It was a transformation that contributed immensely to the theories and investigations surrounding Surrealism.

Synthetic Cubism also challenged the differences between paintingand sculpture. Instead of breaking the image apart and then reassembling it from a number of different perspectives, Synthetic Cubism assembled the image, building it up from a flat surface into a multi-layered object, like a three-dimensional object resting on a two-dimensional surface. In all these ways, Synthetic Cubism approached its accomplishments by way of a clear and intentional paradox: By making work that was ever more false they achieved something ever more real.

Featured image: Pablo Picasso - Three Musicians, 1921, © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio