Tachisme - The Abstract Art Movement of the French

Tachisme was one of the most dynamic and fascinating art movements to emerge in the mid-20th Century, yet it is widely misunderstood. Most writers and historians simply pass Tachisme off as the French version of Abstract Expressionism, because of what they see as similarities between the visual characteristics of the two movements, and because both art movements seemed to emerge, or were at least given names, around the same time, in the early 1950s. But such a superficial analyses seems to me to diminish the artists associated with Tachisme, and it also seems to fundamentally mischaracterize the intent and diversity of their work. What is Tachisme, then, if not just the French version of an American art movement? It may not be so easy to say. Paintings associated with Tachisme tend to be characterized by organic, energetic brush strokes, and their compositions tend to be lyrical and lack recognizable forms, but that is not always the case. The general lack of discernible forms in Tachisme is, however, common enough that it caused Tachisme to become associated with the larger European Post-War movement called “Art Informel.” The word informel did not mean casual; it meant lacking in form. The source of the word Tachisme is “tache,” a French word for “stain,” as in a spilled substance splattered on a surface. Some painters associated with Tachisme, such as Georges Mathieu, developed visual languages that have much in common with spilled splotches of paint, which is again one of the reasons Tachisme has been mischaracterized as the French version of Abstract Expressionism—both movements involved splatter painters. But rather than passing it off an example of Europeans copying Americans, it seems to me that it would be better to actually try to analyze Tachisme according to the tendencies and methods that are unique to it. When given its due consideration, Tachisme is a unique aesthetic position with roots firmly in Europe, that trace their way back at least to the early years of the 20th Century.

Lyrical Roots

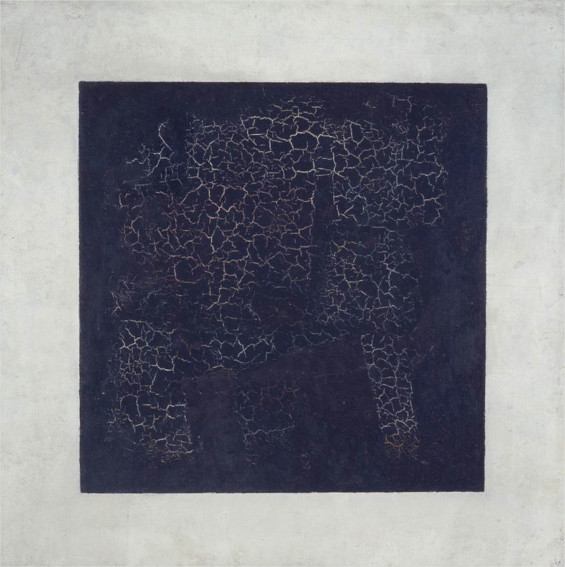

Visually speaking, in admittedly over-simplistic terms, abstract art has always tended towards two seemingly contradictory aesthetic positions: the geometric and the lyrical. “Black Square” (1915) by Kazimir Malevich is a perfect early representative of geometric abstraction. “Composition VII” (1913) by Wassily Kandinsky is a perfect representative of its lyrical opposite. Both positions have been around since the dawn of visual art, and at any given time there have always been artists exploring both types of abstraction, as well as plenty of artists whose aesthetic positions blend the two, creating a spectrum with infinite in-between points. Even when it comes to two artists who supposedly adhere to one extreme position or the other, however, things like intent, method, and medium differentiate the kind of work they make. For example, Kazimir Malevich had different reasons for making geometric art than Donald Judd or Ellsworth Kelly.

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915. Oil on linen. 79.5 x 79.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Likewise, Wassily Kandinsky made lyrical abstract work for different reasons than the artists associated with Tachisme, who we can imagine made their work for different reasons than the Abstract Expressionists. Wassily Kandinsky used lyrical abstraction as a way of finding the visual equivalent to music. Abstract Expressionists were more about channeling the subconscious mind in order to address their angst and anxiety. They were into psychotherapy, and their art extended outward from that way of thinking, and was thus extremely personal and dramatic. Tachisme shares visual qualities with both Kandinsky and Abstract Expressionism, in that it incorporates marks that are intuitive, organic and gestural, but it has nothing to do with music, and little to do with psychotherapy and personal drama. Judging by the work, it has more to do with physicality, materiality, commonalities, and the raw expression of natural energy within a visual field.

Defining Tachisme

One of the earliest artists associated with Tachisme is Hans Hartung. His signature aesthetic position is defined by long, sharply angled, linear marks. His paintings often resemble lines scratched in the sand, or the marks left behind by lashes of a whip. Hartung was making these paintings as early as the 1930s. Another artist associated with Tachisme is Karel Appel, of CoBrA group. Appel embraced a primitivist style that approximated the drawings of children. His work was instinctive, whimsical, and brut. Next we have Georges Mathieu, who I mentioned already had a style that approximated splatters of paint. But his compositions were nothing like those of Jackson Pollock, the Abstract Expressionist paint splatterer. Mathieu avoided the “all-over” style associated with Pollock, and was more methodical, and even traditional, in his compositional choices. One of the most famous artists associated with Tachisme, Pierre Soulages, is even still alive. His work from the Tachisme period is founded in exploration of gesture and brush stroke; it is calligraphic and bold, and rooted in color and line.

In addition to these I mentioned, there are dozens of other artists associated with Tachisme. They hail from all over the world, and are known for a massive range of methods and styles. If there is any hope of defining what Tachisme truly is, we therefore have to look beyond superficialities and ask what each of these diverse artists has in common, if anything. In my opinion the answer has something to do with nature. Some, like Appel, or Jean Dubuffet, thought deeply about the original, primal nature of humanity. Others, like Alberto Burri, were concerned with the forces of nature itself, and the ways nature has of organizing itself in space. Still others, like Jean-Paul Riopelle and Sam Francis, were concerned with the way they could express the powers of nature through their own actions. Meanwhile, artists like WOLS and Antoni Tàpies were most interested in confronting human nature. All of these artists channeled their interest in nature abstractly through direct, physical interventions with their mediums. To me, that means Tachisme is not even remotely the French equivalent of Abstract Expressionism. It is a unique position, which truly acts as an expression of its root word—just like a stain it is based on natural forces, like gravity and movement, and the pure materiality of paint.

Featured image: Georges Mathieu - Vaires, 1965. Huile sur toile. 97 x 195 cm (38¼ x 76¾ in.). Acquis directement auprès de l'artiste par le propriétaire actuel en 2006. Christies collection.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio