Umberto Boccioni and the Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

Early Modernist artists were fascinated with movement. Cubists showed movement by painting subjects from multiple simultaneous perspectives. Orphists focused on color’s vibrational qualities. Dynamists depicted movement through repetition. Futurists expressed movement by aestheticizing speed. Umberto Boccioni was the father of Futurist sculpture. Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, a sculpture depicting an abstracted, quasi-human form in motion, was considered at the time of its making to represent the height of achievement when it came to depicting movement through the plastic arts. As Futurism’s leading art theorist, Boccioni considered the work of other Modernist artists to be mired in what he called “analytical discontinuity,” meaning their attempts to show life disproved themselves through their lack of vitality. With his own work, Umberto Boccioni strove to achieve the elusive aesthetic goal of “synthetic continuity.” Rather than trying to imitate or mimic motion, he intuitively sought to convey the truth of motion through abstract means.

Umberto Boccioni the Painter

Before becoming interested in three-dimensional work, Boccioni was already a highly accomplished painter. He showed little interest in art until he was in his late teenage years, but once art found him he demonstrated raw talent and quickly learned the fundamental classical skills. By the time he joined the Futurists in his late 20s, Boccioni was one of the most skilled painters in the movement. Even by just judging his self-portraits we can see Umberto Boccioni demonstrated a mature grasp of representational drawing skills, paint handling, composition and a mastery of a range of styles from Divisionism to Impressionism to Post-Impressionism.

By 1909, Boccioni had committed himself to deconstructing his style, focusing on the elements that would eventually define the Futurist aesthetic. He elaborated on the emotive power of luminous, vibrant colors, the ability of line to convey light, the manipulation of form to convey motion and the use of the implements, actions and architecture of the industrial age as appropriate modern subject matter. All of those elements are visible in his painting The Morning, from 1909. And less than a year after painting that painting, Boccioni took those elements into the realm of abstraction, painting what many consider to be the first truly Futurist painting, The City Rises.

Umberto Boccioni - three self-portraits, from 1905 (left), 1905 (middle) and 1908 (right)

Futurist Sculpture and Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

Boccioni’s eagerness to experiment is evident in his rapid growth as a painter. It’s no surprise then that once he realized the dynamic possibilities of sculpture he was attracted to the opportunity to revive what he called “that mummified art.” In 1912 he wrote the seminal document defining Futurist sculptural concerns, called The Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture. In it, despite the title he did not limit the discourse to technicalities, but rather demonstrated the full depth of passion and emotion Boccioni was known for in his work. For example, the manifesto begins by calling the existing body of sculpture being exhibited in Europe “so lamentable a spectacle of barbarism and lumpishness that my Futurist eye withdraws from it in horror and disgust.”

Over the course of the year following the creation of this document, Boccioni created a dozen sculptures. He cast them only in plaster, evidently demonstrating the classic Futurist mentality, being concerned more with ideals than with making something that will last through the ages. His sculptures were primarily concerned with the idea of conveying what he called “succession,” or a series of events. He called artists “stupid” who believed that succession could be achieved through visual tricks, such as repetition (as in Dynamism) or painting from multiple perspectives (as in Cubism). He believed that succession should be conveyed by a single abstracted composition, through an “intuitive search for the unique form which gives continuity in space.” Umberto Boccioni used that phrase as the title of one of those first dozen sculptures, which he believed embodied the idea’s essence. The multiple bronze castings of that piece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, that exist in museums around the world today were all made after Boccioni died. The original plaster piece can be found in São Paulo, Brazil, at the Museu de Arte Contemporânea.

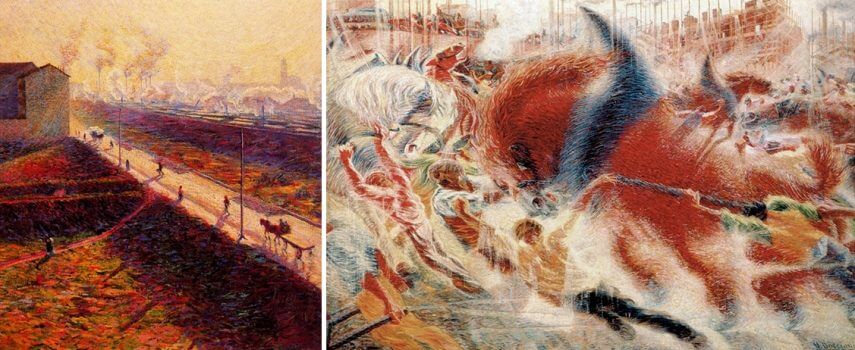

Umberto Boccioni - The Morning (left), painted in 1909, and The City Rises (right), painted in 1910

Development of a Bottle in Space

One of Boccioni’s most intriguing Futurist sculptures is called Development of a Bottle in Space. Without knowing its title, a viewer could easily read the piece as an abstract assortment of geometric forms lumped in a sort of mountain. Or it could be seen as a vision of a futuristic, high-rise cityscape. Even after reading the title the piece could be considered Cubist, as it seems to convey a bottle from multiple simultaneous spatial planes. But according to Boccioni it’s none of those things. It depicts the motion of a manufactured industrial product in the process of assembling itself in physical space.

Unlike the quasi-human Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, there’s no obvious theoretical justification for a bottle to be in motion. That Boccioni chose an inanimate object to demonstrate animation is telling. The piece offers a foreboding clue to the Futurist’s adoration of the mechanized world to which they were reacting. It’s a vision of a self-sustaining industrialized future that has in many ways come to pass, in which products assemble themselves and mechanized movement occurs on its own, free from human interaction.

Umberto Boccioni - Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, Front and side view

The Contemporary Search for Succession

Something that often goes unnoticed about Boccioni and the rest of the Futurists is that there was an inherent contradiction in their ideas. They were supposedly revolting against the burden of history, and embracing the age of the machine. And yet they were doing so through the plastic arts. The first motion picture camera was invented more than a decade before the Futurist Manifesto was published. Why attempt to capture motion in a painting, when it could literally be captured on film?

It’s endearing that these artists, while rejecting the artists of the past, did not entirely reject art itself. They could have replaced their ancient practices entirely with the fast, beautiful, machine-powered worlds of photography and cinema. But instead they chose to confront the modern age with ancient techniques. Knowing that perfect representation was available to them through photography and cinema, they willfully chose abstraction, perhaps for the same reasons so many others, like Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich did. It’s a way not only to show us what is visible to the eye, but also to arrive at something that resides beyond the eye, in the mind, in the heart, or in the spirit. As essential as speed, machines and the industrial age were to the Futurists, the fact that they painted and sculpted reveals that they believed somewhere in their hearts that something ancient, like humanity, was even more important.

Featured Image: Umberto Boccioni - Development of a Bottle in Space, made in 1913, cast in 1950

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio