Vladimir Tatlin and The Monument to the Third International

Intentions are vital to abstract art. Conversations about intent help viewers connect with artists and contextualize their work. Unlike in politics, business or other utilitarian fields, in abstract art intentions are sometimes even more vital than the work itself. When Vladimir Tatlin originally designed his Monument to the Third International, it was with the hopeful intention of inspiring the Russian people to joyfully rebuild their society after the carnage and destruction of revolution and war. Tatlin envisioned that his towering monument would be seen as a truly modern work of art that would help usher in a utopian future for his battered and broken homeland. His intentions were noble, and grounded in his personal beliefs about art. As the founder of Constructivism, Tatlin believed that rather than existing apart from everyday life art should be incorporated into every aspect of daily human existence in a constructive and universally beneficial way.

Revolution and Reformation

It is easily forgotten that the official actions of nations do not always reflect the will of their ordinary citizens. The list of combatant countries in World War I contains many in which outspoken and widespread movements actively, though unsuccessfully advocated not to fight. At the top of that list is Russia. Leading up to the war many ordinary Russians felt it was unjust that disagreements between bureaucrats, business leaders and royals should invite destruction upon the masses. Russian socialist revolutionaries even possessed the borderless, idealistic belief that, as Lenin put it, “workers have no country.”

But Russia, like most of the world’s other major nations, did nonetheless engage itself in World War I, and the results were devastating. The war shattered the Russian social fabric. The food supply was depleted and the public infrastructure was heavily damaged. Before the war had even ended the Russian Revolution began, and as soon as the revolution ended civil war broke out. When the fighting was finally over, the Tsarist regime that had led the country into such misery had been permanently disposed of, and the new socialist regime promised to reform and rebuild Russian society.

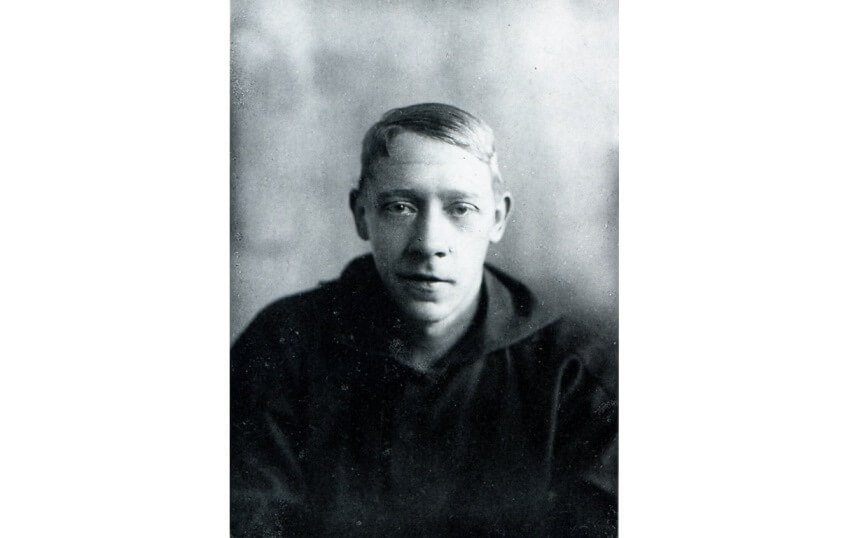

Vladimir Tatlin- portrait

Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde

Integral to the hopefulness Russians felt in the early 1920s was a sense that the creative class was going to play a direct role in evolving their more equitable society. Artists like Kazimir Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin had visions of a new, modern art that would express the coming age. When Tatlin was given the chance to propose new monuments for socialist Russia, he abandoned the historic notion of building figurative statues to heroes of war. Instead, he envisioned creating abstract public monuments that could inspire all people toward a contemplative, meaningful and thoroughly modern future.

The optimism Tatlin felt manifested most famously in his proposition for a massive tower called the Monument to the Third International. The name was a reference to the Communist International, a group that advocated for global communism. The tower was designed to be one-third taller than the Eiffel Tower, making it the tallest building in the world at the time. It would also be made of the most modern material, such as iron, steel and glass, and, being simultaneously practical and abstract, would represent the epitome of constructivist ideals.

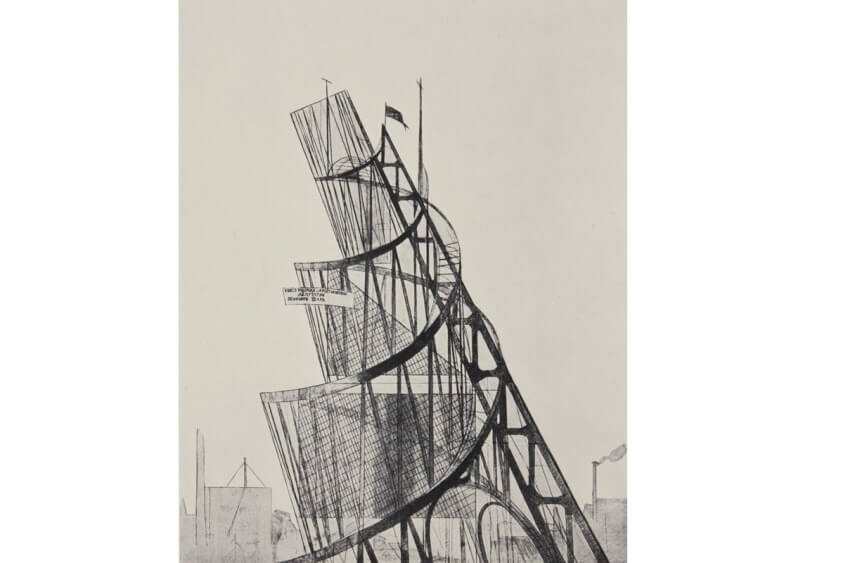

Tatlin - drawing of his Monument to the Third International

Vladimir Tatlin - The Marriage of Abstraction and Utility

Among the practical elements of Tatlin’s Tower was its double-helix frame, which supported a network of mechanical conveyances on which passengers could travel to the various functional spaces. Those spaces included four hanging, geometric structures in which official and public business would be conducted. The lowest of the four structures was intended to house the legislative branch of government and host lectures. The second structure was for the executive branch of government. The third was intended for use by the state run press. And the fourth was a communications studio for radio transmissions, telegraphs and so on. Each geometric structure was designed to rotate at a different frequency, the largest taking a year to complete a rotation and the smallest taking a day.

Perhaps more impressive than its practical elements were the abstract qualities of Tatlin’s Tower. Its four geometric architectural spaces suggested the idealistic collectivism that was supposed to define the modern socialist Russian culture. The upward spiral of its design was strikingly optimistic, and its material components spoke to the re-born nation’s pervasive longing for progress. Its rotating elements evoked a sense of forward momentum and the march of time. Its hollow frame embodied the abstract Modernist ideal of creating volume without mass. And its communication center, located at the apex, symbolized the priority of education, relationships and community. Most importantly of all, the structure was transparent, an abstract promise that unlike in the past, the new Russia would conduct its business in full public view.

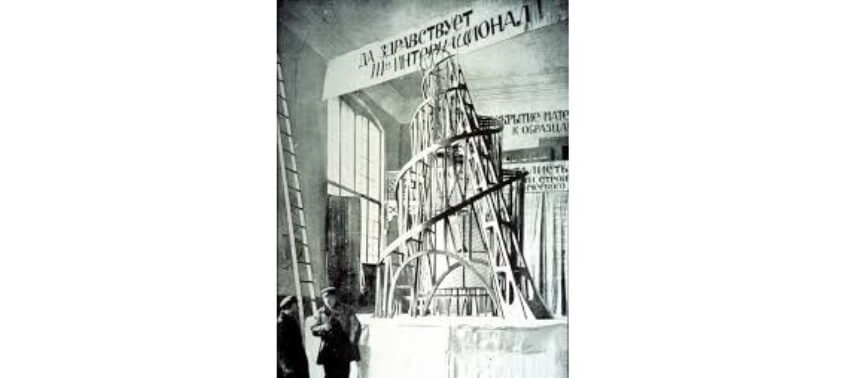

Tatlin - original scale model of the monument from the 1920s

For All Intents and Purpose

It is a disappointing irony that Tatlin’s Tower was never built. There were simply no resources left over after the war to create such a structure. And there were also no skilled Russian builders left who could have successfully engineered Tatlin’s visionary design. The death throes of the very past that Tatlin hoped his tower would transcend held back the utopian future it represented.

Thankfully, nonetheless, the story of Tatlin’s Tower has survived. It provides a powerful and endearing context for the hope and optimism contained within Constructivism. As Tatlin once wrote, “In the squares and in the streets we are placing our work convinced that art must not remain a sanctuary for the idle, a consolation for the weary, and a justification for the lazy. Art should attend us everywhere that life flows and acts.” Although his monument was never built, its promise lives on through photos and the stunning models Tatlin designed, as well as through the power of Tatlin’s intent.

Featured Image: A reconstructed model of Vladimir Tatlin's Monument to the Third International at London’s Royal Academy of Art, 2011

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio