The Lyrical in the Art of WOLS

Whenever we think of lyrical abstraction in painting, we think first of the German artist Wols. Strangely, we do not think of Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, the German citizen who, after his name was mangled in a telegram, changed it permanently to the mistake. We think of Wols, the new being created by that accident. The part of Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze that eventually manifested as Wols existed long before the telegraph mistake, of course. Alfred was already an artist, an outsider: a stranger in the world. The adoption of the name Wols was a form of liberation, an act that freed him to determine for himself what his identity would become. Various theories claim that the choice to adopt the name Wols was only a joke to Alfred, or a ruse to evade German authorities during wartime. Even if that is so, the choice to become Wols nonetheless expresses a poetic truth: that artists are always of two minds. In this case, the mind called Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze knew it must survive, and somehow had to work within the known world. But the mind we call Wols wanted only to explore and express the depths of the unknown.

Becoming Wols

Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze was born in Berlin in 1913. Just 38 years later he would die. But in his short life he would manage to make a remarkable transformation as an artist, from realist photographer to lyrical abstract pioneer. His first artistic medium was photography perhaps only because he received a camera as a gift at age 11. The photographs he took range from simple portraits to grotesque, seemingly absurd compositions of everyday objects. Many of his photographs contain corpses of butchered animals along with mundane items such as buttons and eggs. Others are run of the mill nudes. All reveal an eye for capturing the fleeting, uncanny oddness of real life, as perceived by someone decidedly outside the norm.

Sometime in his youth, Alfred also began to draw, a fact known from the diary his mother kept. He also briefly studied art at the Bauhaus, where he befriended László Moholy-Nagy, who recommended to Alfred in 1932, as the Weimar Republic was failing and the tide in Germany was turning once again toward a war footing, that he leave Germany and go to Paris. Alfred did leave, traveling Europe for years while awaiting a French visa. After briefly being jailed in Spain, and working many odd jobs, finally in 1936, he was able to move legally to Paris.

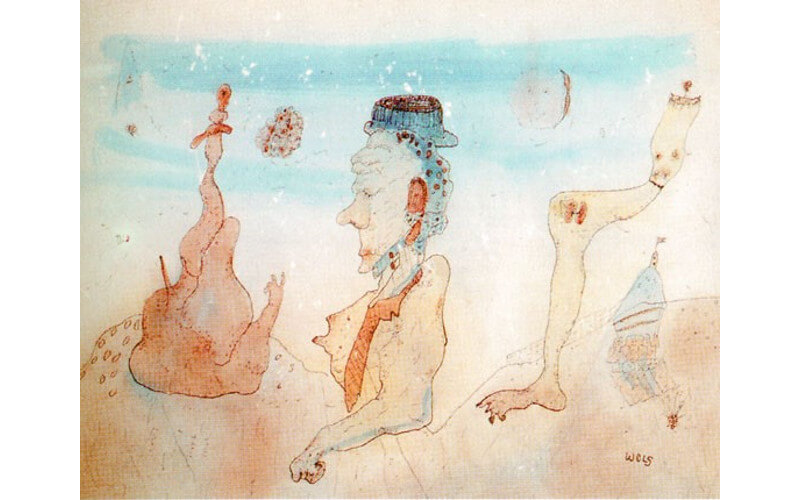

Wols - L'homme terrifie, 1940. Watercolor and India ink on paper. 23.6 x 31.5 cm. © Wols

Wols - L'homme terrifie, 1940. Watercolor and India ink on paper. 23.6 x 31.5 cm. © Wols

Always On the Run

In Paris, in 1937, he received his fateful, garbled telegram, which game him his new alias. He began showing his photographs in galleries, and received positive attention. But just as he was beginning to gain a reputation, war broke out and he was locked up in a French internment camp as a citizen of a combatant country. While in the internment camp, Wols turned seriously to painting, working in watercolor and ink on paper. Most of his works dating from this time are figurative and reflect the artists who influenced him, such as Joan Miró and the Surrealists. Though he had not yet fully transitioned into abstraction, his watercolors reveal his intuitive gestural technique, and his poetic, lyrical grasp of the inherent emotion and drama of human existence. His surrealist watercolors are disturbing, but also ethereal, the products of a mind caught in one reality but searching for another.

During the war, Wols managed to escape from his internment camp and hide out in the countryside, where he continued to paint. When war finally ended he was able to return to Paris. He exhibited his surrealist watercolors, and they were well received by the public as well as by other artists. But having lived more than a decade as a transient, a prisoner, an escapee and a stranger he found himself ever more drawn inward. Despite receiving attention for what he was doing, his instinct was nonetheless to gravitate toward something new.

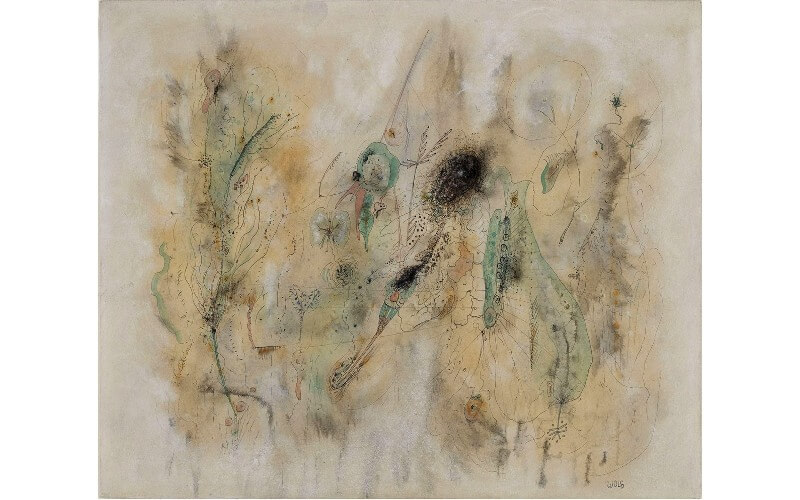

Wols - Untitled (Green Composition), 1942. Pen and ink, watercolor, white zinc and scraping on paper. 23.3 x 27 cm. © Wols

Wols - Untitled (Green Composition), 1942. Pen and ink, watercolor, white zinc and scraping on paper. 23.3 x 27 cm. © Wols

Wols and Lyrical Abstraction

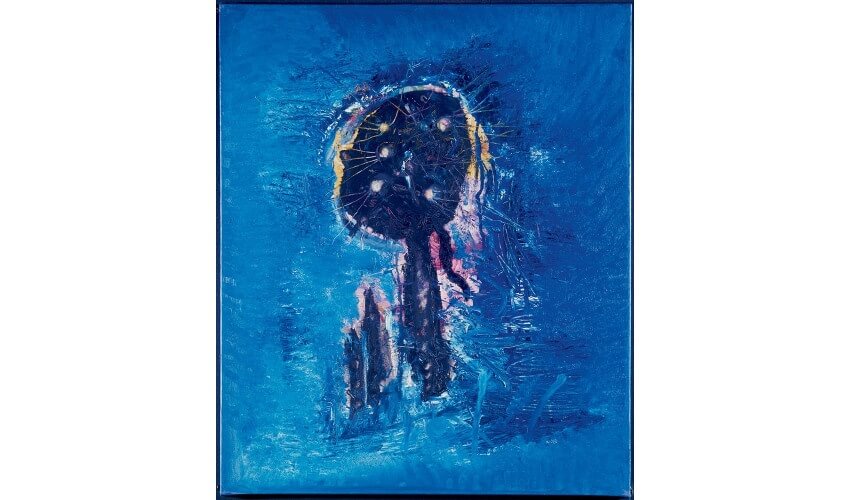

In the late 1940s, Wols began painting with oils. He developed a radical, highly personal, abstract style that incorporated staining the canvas, rubbing and scratching the paint in with his hand, dripping paint in controlled ways and energetic, gestural marks. The intense, expressive, primitive aspects of these paintings placed him foremost among post-World War II painter making what the French art critic Michel Tapié called Art Autre, or art of another kind. Writing in 1952 about the abstract style of these artists, Tapié wrote, “an entire system of certainty has collapsed.”

To describe this new generation of abstract artists, Tapié coined the term lyrical abstraction. The paintings of Wols epitomize what Tapié called a “fertile and intoxicating anarchy,” “an invitation to adventure,” and a feeling of “going into the unknown.” Wols was lyrical in the classic sense. He abandoned objectivity in favor of pure, subjective emotion. His bold colors expressed anger, passion, isolation and fear. His stained and rubbed surfaces expressed the ambiguous border between reality and possibility. His scrawled, scratched and quickly brushed lines expressed the anxiety of his time.

Wols - Untitled (Painting), Painting, 1946-47. Oil on canvas. 81 x 81.1 cm. © Wols (Left) / Wols - Its All Over The City, 1947. Oil on canvas. 81 x 81 cm. © Wols (Right)

Wols - Untitled (Painting), Painting, 1946-47. Oil on canvas. 81 x 81.1 cm. © Wols (Left) / Wols - Its All Over The City, 1947. Oil on canvas. 81 x 81 cm. © Wols (Right)

The Present Eternity

It has been reported that throughout World War II, Wols had been trying to acquire the proper permission to move to America. He is said to have been chronically depressed by his inability to do so, which apparently contributed to his well-whispered-about alcoholism. Maybe these things are true. Or maybe they are only the snippets of fact that spill out of a person trying to improvise a life, and then get passed on by people who want to attribute specificity to what is ambiguous.

If we take the time to open ourselves up to them completely, the lyrical visual poetry contained in the abstract paintings Wols made in the half-decade before he died liberate us from any need to point to the direct causes of his suffering, his anxiety, his love or his joy. They speak for themselves with something timeless and universal. But if we still need something more solid to grasp onto while considering his work, we can also look to his book. Wols collected quotes and thoughts about art and life and published them in a book called Aphorisms in 1944. In one poetic passage in the book he gives us all the guidance we need to understand his art. “Nothing can be explained,” he writes, “all we know is the appearances…The Abstract that permeates all things is ungraspable. In every moment, in every thing, eternity is present.”

Wols - Blue Phantom, 1951. Oil on canvas. 73 x 60 cm. © Wols

Wols - Blue Phantom, 1951. Oil on canvas. 73 x 60 cm. © Wols

Featured image: Wols - Light Focus (detail), 1950. Gouache and pen and ink on wove paper. 15.9 x 14 cm. © Wols

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio