These Artists Continue to Redefine 3D Printed Art

I heard a joke once at an art opening featuring 3D printed art. It went something like this: “How do you know you are looking a piece of 3D printed art?” Answer: “Because everybody tells you.” It made me laugh first of all because it is true, people tend to be so excited about this medium that they just cannot resist buzzing about it. And secondly I laughed because in almost every case of 3D printed art I have seen, the fact that it was made using a 3D printer seemed to me to be irrelevant. Nothing about these works seemed to demand the technology. It could all have been done using some other means. Which begs the question: What is everybody buzzing about? 3D printers are just tools, no different in their nature than, say, projectors. I have never had someone walk up to me in a gallery, point to a drawing and say, “That was made using a projector.” But then again, I have never had anyone walk up to me and say, “That was made entirely by assistants while the artist was on vacation.” The point being, it does not matter. Once the idea for an artwork is formed and steps are taken to realize it, it does not make a difference whether the actual work is carried out by this machine or that machine, or this pair of hands or that pair of hands. The fact that a 3D printer was used to make art does not in any way validate the work—it is only one aspect of the experience, and usually the least important aspect at that. This, at least, is my opinion. So when I was asked to write about artists who are redefining 3D printed art, I adopted the perspective that I should feature artists who have interesting ideas and are making work I would like to talk about regardless of how the work is getting made. So with that caveat made, here are seven artists using 3D printing technology to make their work who are, through the strength of their ideas, redefining the place of this new tool in contemporary aesthetics.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

If you have ever heard the term Relational Aesthetics, or Relational Art, you have probably heard of Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija. His work was essential to the rise in popularity of this type of art experience in the 1990s. His most famous relational art exhibition was called pad thai. For the exhibition, which was held at the Paula Allen Gallery in New York in 1990, rather than creating and showing work, the artist cooked pad thai in the space and served it to visitors to the gallery. The exhibition helped define relational aesthetics as an exploration of the idea that artists are not so much makers, but facilitator of experiences. The human relationships that emerge out of those experience are what is most important.

More recently, Tiravanija is receiving attention for his immersive installation at Art Basel Hong Kong 2017, which questioned the role of art and art history within the human experience. The piece was essentially a giant maze constructed out of traditionally tied bamboo. Visitors entered the maze, and while finding their way within it they gradually encountered five 3Dprinted bonsai trees, each one set atop a wooden pedestal inspired by the sculptural bases once created by the artist Constantin BrâncuÈ™i. The fact that the bonsai trees are 3D printed is not the most important thing. It is the fact that they are artificial that matters. The point of a bonsai tree is that it is a natural thing interfered with by human hands in such a way that the human interference is unrecognizable. In this case, the artificiality of the trees combined with the evocative notions inspired by the maze, all mixed in with the art historical references, all works together to give viewers an abstract, open-ended experience that commands social interaction in order to comprehend its potential levels of meaning.

Rirkrit Tiravanija - Untitled 2017 (no water no fire), 2017. 3D printed bonsai tree on wooden base. © Rirkrit Tiravanija, Courtesy of gallery Neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Rirkrit Tiravanija - Untitled 2017 (no water no fire), 2017. 3D printed bonsai tree on wooden base. © Rirkrit Tiravanija, Courtesy of gallery Neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Wieki Somers

The word vanitas comes from Latin, and means emptiness. It was used in the Netherlands in the 16th and 17th Century as the name for a type of still life painting. Vanitas Paintings are basically still life paintings showing collections of banal, material objects, usually along with human skulls, illustrating the meaninglessness of the pursuit of earthly things. Dutch artist and designer Wieki Somers used the visual language common to Vanitas Paintings in a series of 3D printed artworks she created in 2010, in response to a design contest that asked designers to “think about the notion of progress.” Titled Consume or Conserve, the series she created featured three still life sculptural tableaus. Each tableau consisted of banal, everyday products, such as a scale, a vacuum cleaner and a toaster, entirely 3D printed out of the ashes of human remains.

In her explanation of the work, Somers pointed out that human technology has advanced to the point that we could soon be faced with the prospect of eternal life. “But,” she asked, “what is an eternal life good for if we use it only to continue being mere consumers who strive for more and more products, regardless of the consequences? Continuing on this road of uncriticized innovation, one day we might find ourselves turned into the very products we assemble.” She followed that concept to its logical conclusion, literally creating products out of the remnants of once precious human lives.

Wieki Somers - Consume or Conserve, 2010. 3D printed human remains. © Wieki Somers

Wieki Somers - Consume or Conserve, 2010. 3D printed human remains. © Wieki Somers

Stephanie Lempert

New York based artist Stephanie Lempert makes work about communication. She hopes to draw our attention to language and the ways we use it to communicate our stories, our histories and our memories to create meaning in our lives. A multi-dimensional artist, Lempert uses a variety of media. One of her most concise bodies of work is a series called Reconstructed Reliquaries, for which she created sculptural relics that are literally built from language. These objects speak for themselves on multiple levels. Lempert created them through the use of 3D printing software. She prefers, however, to use the industry standard, but less buzz-worthy terminology, rapid prototype sculpture.

Stephanie Lempert - Reconstructed Reliquaries, In Search of Lost time, 2011. Rapid Prototype Sculpture. © Stephanie Lempert

Stephanie Lempert - Reconstructed Reliquaries, In Search of Lost time, 2011. Rapid Prototype Sculpture. © Stephanie Lempert

Theo Jansen

Dutch artist Theo Jansen first became known in the 1990s when he started creating his Strandbeests, gigantic, kinetic creatures that seem to walk around by themselves. They are, as he calls them, “self-propelling beach animals.” You may have seen footage of them crawling poetically across beaches around the world. Part designer, part engineer and part artist, Jansen once said, “The walls between art and engineering exist only in our minds.” Normally, his large creations are made from PVC tubes. But recently, he started making his creations available to almost anyone by offering miniature, 3D printed Strandbeests for sale for only €160.00. Most wonderfully, anyone who can get ahold of the plans can have one printed out. As his website states, “Theo Jansen's Strandbeests have found a way to multiply by injecting their digital DNA directly into 3D print systems.”

Theo Jansen - Miniature 3D printed Strandbeest. © Theo Jansen

Theo Jansen - Miniature 3D printed Strandbeest. © Theo Jansen

Nick Ervinck

The work of Belgian artist Nick Ervinck screams with vivid color and thrilling forms, embodying the notion that somehow an object that occupies space can also create space. His sculptures come in all sizes, from miniatures to monumental public works. By designing his own 3D printing tools and techniques, he is pushing the boundaries of this tool, utilizing it not just as an end in itself but as an idiosyncratic method of realizing his personal visionary creations.

Nick Ervinck - EGNOABER, 2015. Polyurethane and polyester. 710 x 440 x 490 cm. © Nick Ervinck

Nick Ervinck - EGNOABER, 2015. Polyurethane and polyester. 710 x 440 x 490 cm. © Nick Ervinck

Shane Hope

Brooklyn-based artist Shane Hope uses 3D printed cellular structures as one element of his abstract paintings. From afar, they appear to be painterly works piled high with impasto brushstrokes, but upon closer examination stacks of assembled nano-structures reveal themselves. That this element has been 3D printed is not obvious nor necessary to ones appreciation of the works, but consideration of the implications of the technology add layers to their potential meaning.

Shane Hope - Femtofacturin' Fluidentifried-Fleshionistas, 2012. 3D-printed PLA molecular models on acrylic substrate. © Shane Hope, courtesy of Winkleman Gallery, New York

Shane Hope - Femtofacturin' Fluidentifried-Fleshionistas, 2012. 3D-printed PLA molecular models on acrylic substrate. © Shane Hope, courtesy of Winkleman Gallery, New York

Monika Horcicova

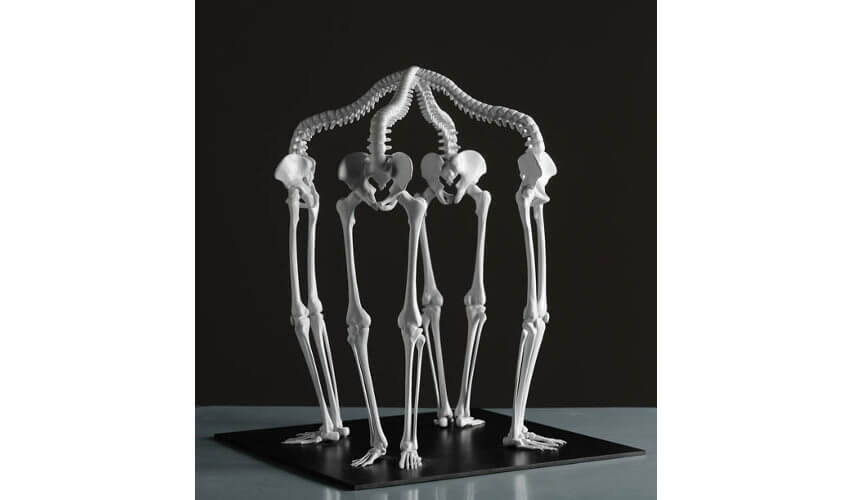

The work of Czech artist Monika Horcicova is haunting and beautiful. She returns to themes of human bones and skeletal structures, creating compositions that challenge our ideas of our own purpose and potential. Though not working exclusively in the medium, she often used 3D printing technology to create her plaster composite sculptures.

Monika Horcicova - K2, 2011. 3D printed plaster composite. © Monika Horcicova

Monika Horcicova - K2, 2011. 3D printed plaster composite. © Monika Horcicova

Featured image: Rirkrit Tiravanija - Untitled 2013 (indexical shadow no.1), 2013-2017. Stainless steel base (3 x panels), 3D printed plastic (Bonsai Tree), stainless steel cube (plinth). 35 2/5 × 35 2/5 × 35 2/5 in, 90 × 90 × 90 cm. © Rirkrit Tiravanija and Pilar Corrias Gallery, London

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio