How Ad Reinhardt Taught Us to Look at Modern Art

What does it mean to be a purist? Is it like being close-minded? Or is the quest for purity inherently noble, like the pursuit of perfection? To the American abstract artist Ad Reinhardt, purity was essential to fine art. In his 1953 essay, “Twelve Rules for a New Academy,” Reinhardt defined fine art as “art emptied and purified of all other-than-art meanings.” He went on to explain that, “The more uses, relations and “additions” a painting has, the less pure it is. The more stuff in it, the busier the work of art, the worse it is. ‘More is less’.” This may sound like a strange statement from a painter associated with the Abstract Expressionists, artists who definitely put more onto their canvases, not less. But although Reinhardt began his career painting expressive, dynamic canvases, his quest for purity drastically altered his approach over time. He so dramatically reduced the content in his paintings over the course of his career that in the final years of his life he painted only with the color black. By the time he died in 1967, he was so confident of the purity of his efforts that he proclaimed that he had painted the last paintings that were ever needed.

Art Made Fine

The quest for purity might seem better suited for a monastery than an art studio. But Ad Reinhardt was as much a philosopher as he was an artist. And one of his best friends was in fact a monk in a monastery. Reinhardt regularly exchanged letters with him, whimsically trading viewpoints on the nature of life and art. In graduate school Reinhardt studied art history, a topic about which he knew more than perhaps any other artist of his generation. Perhaps his interest in discovering the ultimate manifestation of purity in art had as much to do with intellectual and spiritual curiosity as with his desire to define his own relevance to the continuum of art history.

When he first began exhibiting his paintings in New York in the 1940s, they were in line with the dominant emerging style of the time, Abstract Expressionism. They were painterly, gestural, full of vivid colors and alive with abstract markings. Less than a decade later he passionately disavowed all of those things, publishing a dogmatic, almost comically specific, often contradictory manifesto describing the precise method of making pure, modern paintings: paintings that incidentally were nothing like his own early works. If that seems paradoxical, it helps to remember Reinhardt’s own famous words: “Art is too serious to be taken seriously.”

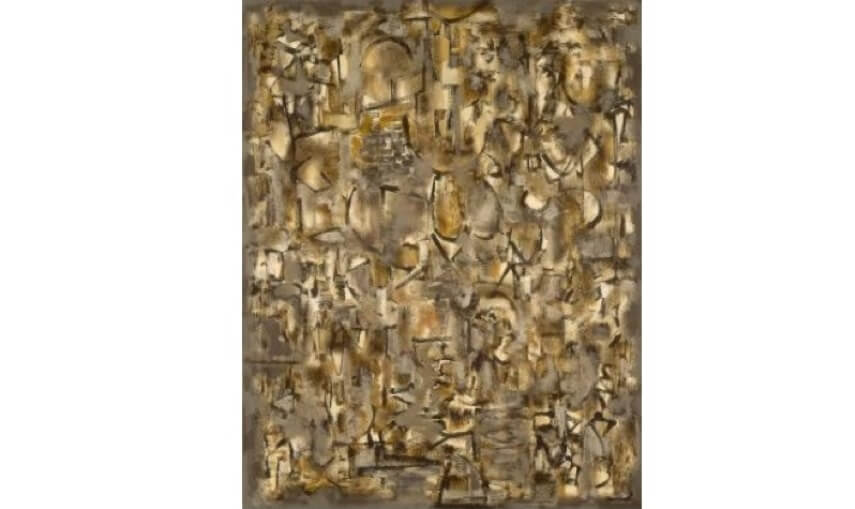

Ad Reinhardt - Abstract Painting, 1960. Oil on canvas. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Dismantling the Avant-Garde

To understand the cultural climate in which Reinhardt worked, it helps to look back at the history of Modernism. Prior to World War II, almost all avant-garde art movements originated outside of America. After World War II, America gave birth to some of the most influential Modernist movements of the Century, including Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and Post Expressionism. What happened to precipitate this change in the influence of American art? It had more to do with politics than with art.

Following the German Revolution in the aftermath of World War I, a representative government came to power in Germany called the Weimer Republic. This democratically elected government instituted wide-ranging social, political and economic reforms that led to vast cultural changes throughout Germany. Within this transformative environment German Modernism flourished. The Bauhaus was established the same year as the Weimer Republic, and in the same city, and over the next 14 years Germany evolved into a leading progressive force in the arts.

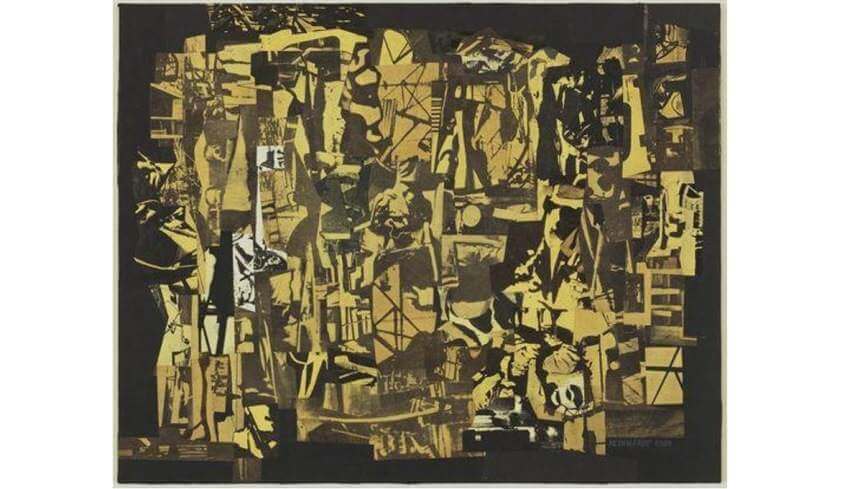

Ad Reinhardt - Newsprint Collage, 1940. Cut-and-pasted printed paper and black paper on board. 15 7/8 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Dark Side of Purism

When the stock market crashed in 1929, Germany, like most other Western countries, saw its economy collapse. The ensuing global depression caused much frustration in the lives of regular working people. When the Nazi Regime came into power in Germany in 1933, it was under the guise of restoring Germany to its historic greatness and reversing the trends of the recent past. One of the first things the Nazi Party did was exert influence over German culture. Modern art was a key target.

Led by Adolf Hitler, the Nazis developed a concept of pure German art. It included only traditional, classical art that adhered to their definition of racial and nationalistic identity. Any art outside of that definition was called degenerate. So began an exodus of avant-garde artists from Germany. And as Nazi influence widened beyond Germany, modern artists across Europe found themselves under the same persecution as well.

Ad Reinhardt - Study for a Painting, 1938. Gouache on paper. 4 x 5 in (10.2 x 12.8 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Re-Assembling the Avant-Garde

Throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, any European modern artist with the means found a way to go abroad. As one of the only global capitals not under siege by fascist powers, New York City became a beacon for avant-garde artists from around the world. Those newly arriving artists mingled with the already vibrant New York abstract art scene, which included American-born artists like Jackson Pollock as well as artists like Willem de Kooning and Arshile Gorky who had immigrated there after World War I. Out of this culture the first American Modernist art movements emerged.

Ad Reinhardt came into artistic maturity as a member of this generation of Post-World War II avant-garde New York artists. He was fully engaged with the vibrant mix of political, philosophical, social and cultural conversations that were taking place in this diverse, international community. He participated in protests and took part in the scene in every conceivable way. But he disagreed with his contemporaries in one fundamental way. While they considered their lives and their art to be intertwined as one holistic experience, Reinhardt believed that was the wrong path. As he put it: “Art is Art. Life is life.”

Ad Reinhardt - Study for a Painting, 1939. Gouache on paper. 3 7/8 x 4 7/8 in (10 x 12.5 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Search for the Invariant

As a way of evolving his artwork away from that of his contemporaries, Reinhardt formulated an idea of the “enlightened object,” a work of art that did not reference any outside thing, any outside idea, but simply existed as a singular example of its pure self. The enlightened object was a form of what a spiritualist might call the “invariant,” the grand ultimate, the unchanging substance that even in the midst of transformation does not transform. Essentially he was looking for the art version of God.

Reinhardt sought the invariant through negation, meaning that rather than defining what pure art is he defined what pure art is not. His 12 Rules For a New Academy, published in 1953, contained his list of negations, phrased as rules for how to arrive at pure art. These rules included: No realism, no impressionism, no expressionism, no sculpture, no plasticism, no collage, no architecture, no decoration, no texture, no brushwork, no sketching ideas beforehand, no forms, no design, no colors, no light, no space, no time, no size, no movement, no subject, no symbols, no images and no pleasure. He added, “Externally, keep yourself away from all relationships, and internally, have no hankerings in your heart.”

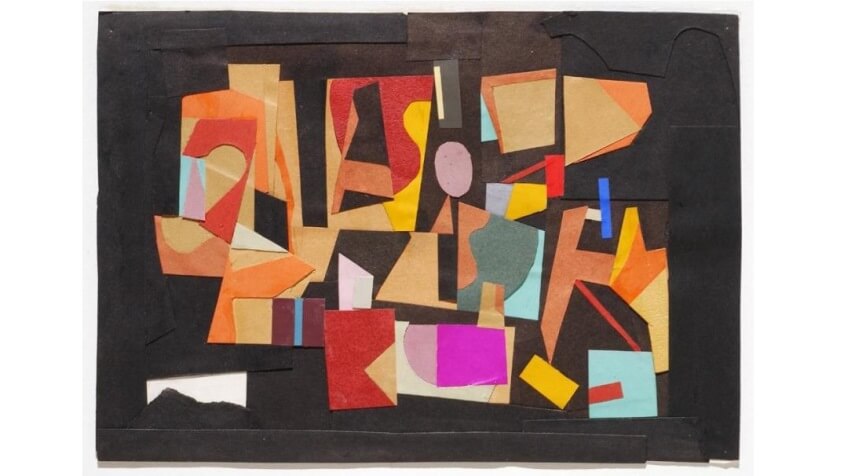

Ad Reinhardt - Paper Collage, 1939. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington DC. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Changing With Change

It is vital to keep in mind while reading 12 Rules For a New Academy that Reinhardt worked as a comedy writer in college, and also that he was a spiritual and philosophical person. He had a sharp wit and often intentionally spoke in paradoxical statements. Even if he did believe that all of his rules were possible to follow individually, he also must surely have known that to follow them all simultaneously meant some would be violated.

For example, when it came to the Black Paintings he spent the last 12 years of his life painting, he referred to them as, “A free, unmanipulated, unmanipulatable, useless, unmarketable, irreducible, unphotographable, unreproducible, inexplicable icon.” But they were not free; they were the product of an ideological, dogmatic system. And as for being unphotographable and unmarketable, they in fact quickly sold, and continue to come up for sale regularly at auction today, with fine photographs included in the catalogues. So was Reinhardt making a joke? Or was he making a more profound statement about the complexities of making and talking about abstract art ?

Ad Reinhardt - Untitled, 1947. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Changeless State

Understanding Reinhardt means understanding his culture. Reinhardt was part of an art scene dominated by passionate, emotional, personal and painterly work. His response to it was to advocate for its opposite. When artists passionately advocated for art to be re-integrated into everyday life, Reinhardt insisted that art and life are separate. He claimed to have painted the last paintings, but as an art historian he knew that the end of painting would never come, as long as there are artists willing to paint.

Some understanding of Ad Reinhardt is found in this quote from Bruce Lee: “To change with change is the changeless state.” By offering an alternative to the dominant trends of the moment, Reinhardt insured art history would continue. Like the Black Square of Kasimir Malevich, the Black Paintings of Ad Reinhardt did not end painting, but rather pushed the continuum forward. By being dogmatic he was not insisting there was only one way, he was giving a gift to the next generation: an enemy to work against: a purist to resist and an ideology to defy.

Featured Image: Ad Reinhardt - Number 6, 1946. Oil on masonite. © 2018 Estate of Ad Reinhardt / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio