The Dark, Abstract Art of Adolph Gottlieb

Adolph Gottlieb was one of the key figures in mid-20th Century abstraction. His paintings are emotive, sparse, and primitive, and many people consider them to be dark. But Gottlieb saw himself as the opposite of dark. He felt he was energetic, complex, passionately modern, and someone who was shining a light, leading the way with his art toward something better for humanity. Born in New York City at the beginning of one of the most tumultuous times in human history, Gottlieb definitely came to maturity in a dark: a time of social, political and economic distress, when the future of society was in question in a real, concrete sense. It is clear not only from his art but from his writings that the anxieties and ambiguities of World War I, the Great Depression and World War II absolutely contributed to the development of his aesthetic vision. But that aesthetic vision was not only one of sadness or doom, as so many critics have suggested. It was in fact one through which Gottlieb simply strove to communicate the truth about the human heart and mind, in a hopeful way. Perhaps it is unavoidable that such truth as Gottlieb perceived it must include some degree of madness and chaos. But the extensive body of work Gottlieb left behind when died in 1974 also included the beautiful, the serene, the peaceful, and the sublime. Those paradoxical complexities, which defined his sometimes controversial world view, ultimately led Adolph Gottlieb to redefine abstract art, and resulted in the creation of an oeuvre that is only now beginning to be recognized for its true brilliance and light.

An Artist at Heart

Adolph Gottlieb was born into a working class, immigrant family in New York in 1904. Compared to many of the other kids growing up on the Lower East Side at the time he was offered a tremendous start in life, as his parents built a successful stationary business and hoped to hand it down to him one day. But quite young he knew for certain that all he wanted to be was an artist. He was so certain of that fact that he dropped out of school at age 15 to commit himself fully to his art. He attended lectures at the Art Students League, an artist-run institution where many artists who eventually become part of the Abstract Expressionist movement attended classes. And then, at just age 17, Gottlieb left for Europe, earning his passage by working aboard a ship heading to France.

His youthful belief in his abilities paid off overseas, as he quickly became acquainted with the world of European Modernism. In contrast to American art in the 1920s, European art at the time was fantastically inventive. He was exposed to Fauvism, Cubism, Suprematism, Futurism and Geometric Abstraction. He frequented museums and attended whatever free art classes he could find. And when his visa ran out, he spent nearly another year traveling throughout Europe. Along the way, he became convinced that European artists were connected to something important. In particular he became fascinated with the spreading influence of tribal art, a trend that inspired him to reject the colloquialism of figurative American art in lieu of seeking universalities within ancient symbols and centuries old visual traditions.

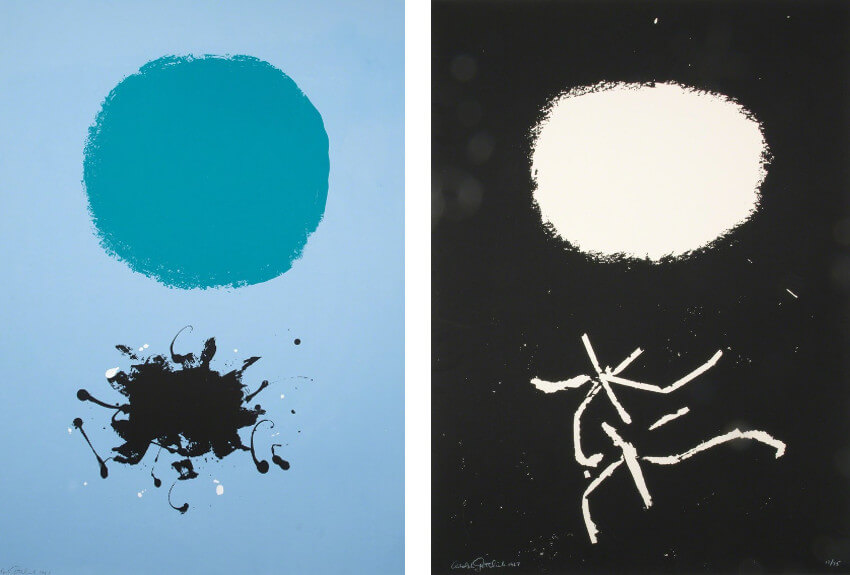

Adolph Gottlieb - Black Splash, 1967, Color silkscreen, 31 1/8 × 23 1/8 in, 79.1 × 58.7 cm (Left) and Flying Lines, 1967, Color silkscreen, 30 × 22 in, 76.2 × 55.9 cm, photo credits Marlborough Gallery

Adolph Gottlieb - Black Splash, 1967, Color silkscreen, 31 1/8 × 23 1/8 in, 79.1 × 58.7 cm (Left) and Flying Lines, 1967, Color silkscreen, 30 × 22 in, 76.2 × 55.9 cm, photo credits Marlborough Gallery

The Philosopher Artist

When Gottlieb returned to New York in 1922, he brought back a sense of his own responsibility as an artist. He saw himself as a modernizing force for his culture, and embraced the notion that artists should be philosophers and agents of social change. He finished his art schooling, and over the next several years became friends with a cadre of other artist/philosophers, such as Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, David Smith and Milton Avery, some of whom would eventually become the most famous American artists of their generation. Gottlieb and his compadres were anomalies. They were abstract artists, or at least artists who made art that was interpreted as being abstract, but they were also eager to talk publicly about the meaning of their work.

At that time avant-garde artists, and especially abstract artists, were not understood in the United States, and were definitely not widely respected—not even in New York. Many had difficulty advocating for themselves and their worth, and especially for the value of Modernist aesthetic ideals. But Gottlieb was a natural advocate and a born communicator. He was politically and socially engaged, and was quick to speak up in favor of what he saw as important. In 1935, Gottlieb and his friend Mark Rothko (then known as Marcus Rothkowitz) put their beliefs into action by forming a group called The Ten. It includedLou Schanker, Ilya Bolotowsky, Ben-Zion, Joe Solomon, Nahum Tschacbasov, Lou Harris, Ralph Rosenborg and Yankel Kufeld. In open protest of the prevailing trends in the New York curatorial scene, The Ten exhibited their abstract work together, rejecting what they called “the reputed equivalence of American painting and literal painting.”

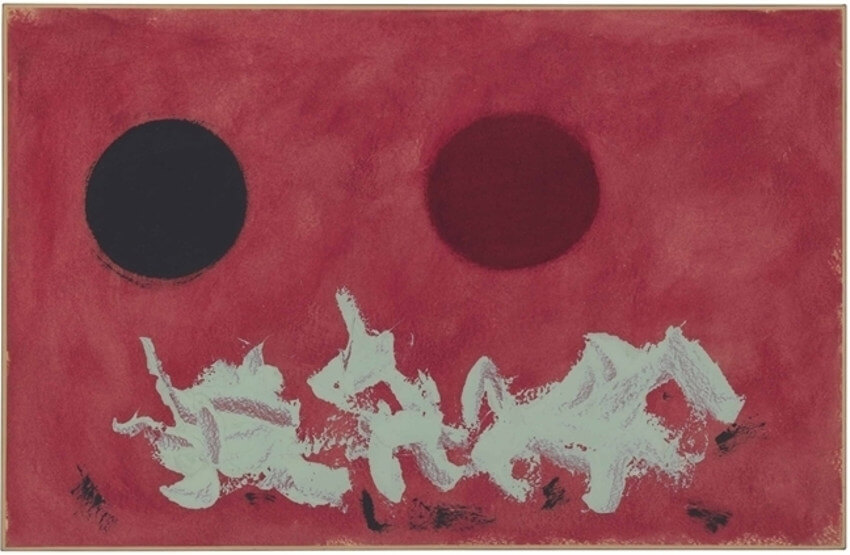

Adolph Gottlieb - Red Ground, Oil on paper mounted on canvas

Adolph Gottlieb - Red Ground, Oil on paper mounted on canvas

The Pictographs

One of the first advancements toward the mature abstract style Gottlieb eventually developed came in the early 1940s, in the form of his Pictograph paintings. These works were essentially attempts at creating a new symbolic language of images that could communicate universal emotions and feelings. Gottlieb conceptualized his Pictographpaintings in such a way that their surface was flattened, eliminating depth and any sense of illusion that could be associated with their figurative elements. He also democratized all areas of the canvas in a prescient reference to what would soon be called “all-over” painting. HisPictographs employed a rawness reminiscent of childlike markings, and evoked the aesthetic tendencies of tribal societies.

In a sense, Gottlieb was trying to create a new image alphabet in the tradition of hieroglyphics or Chinese kanji. But instead of attempting to communicate specific narratives, he was attempting to distill his statements down to the bare essentials. Rather than spelling out the myths he was referencing, he attempted to communicate the collective human feelings that inhabit their core. To achieve this goal he carefully created images that were totally original and free from outside associations, hoping their universal nature would transcend the petty cultural differences that kept people apart.

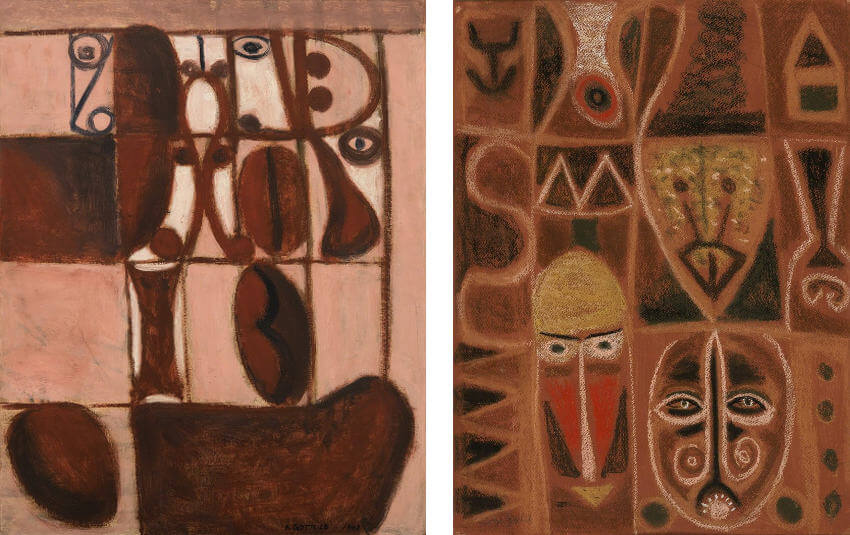

Adolph Gottlieb - Pictograph, 1942, Oil on artists board, 29 1/4 × 23 1/4 in, 74.3 × 59.1 cm, photo credits Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York (Left) and Untitled, 1949, Pastel on paper, 24 × 18 in, 61 × 45.7 cm, photo credits Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco (Right)

Adolph Gottlieb - Pictograph, 1942, Oil on artists board, 29 1/4 × 23 1/4 in, 74.3 × 59.1 cm, photo credits Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York (Left) and Untitled, 1949, Pastel on paper, 24 × 18 in, 61 × 45.7 cm, photo credits Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco (Right)

Imaginary Landscapes

As Gottlieb developed his Pictographs, he engaged in a process of simplification. Through that process he arrived at a series of works he called Imaginary Landscapes. Unlike the Pictographs, which placed no clear emphasis on any one part of the image, Gottlieb separated the picture plane in these paintings into two distinct areas through the introduction of a horizon line. Below the line, Gottlieb added pictographic scrawls. Above the line, he added colored geometric shapes. The Imaginary Landscapes suggested a hierarchical relationship between the two types of images. Depicted as subservient is a scrawling, emotional, complicated expression of human angst. Hovering above is a simple, direct expression of universal purity.

The Imaginary Landscape then became further simplified into what Gottlieb called Burst paintings. In these works he eliminated the horizon line, but retained the scrawl at the bottom and the unified shape at the top. The Bursts made use of large fields of color, and unified the element of color with that of shape. They invited contemplation on an almost sacred level, and seemed to communicate the concept of a symbiotic relationship between some higher and lower consciousness.

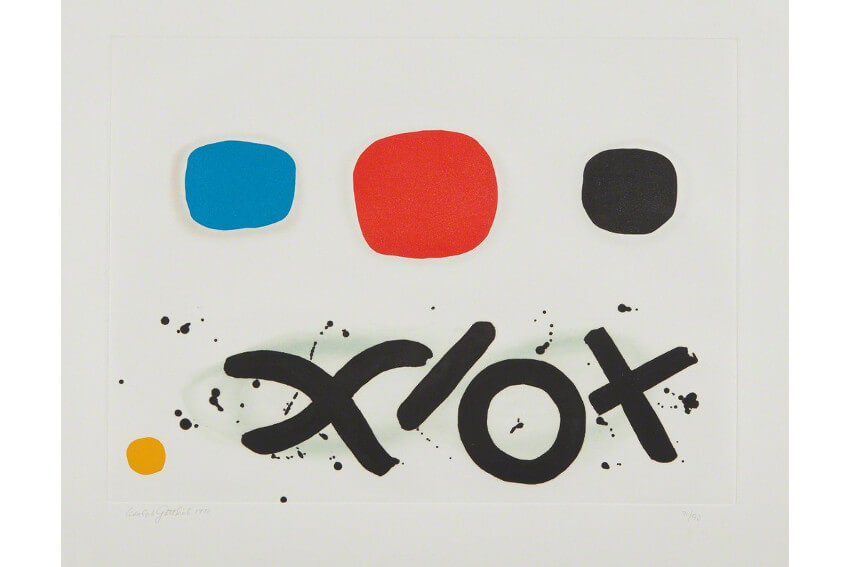

Adolph Gottlieb - Imaginary Landscape, 1971, Aquatint in colors, on Fabriano paper, with full margins, 26 3/10 × 32 1/2 in, 66.7 × 82.6 cm

Adolph Gottlieb - Imaginary Landscape, 1971, Aquatint in colors, on Fabriano paper, with full margins, 26 3/10 × 32 1/2 in, 66.7 × 82.6 cm

The Legacy of Adolph Gottlieb

In 1970, Gottlieb had a stroke and lost the use of the left side of his body. He continued making work nonetheless, creating some of the most profound and extreme expressions of his Burst series just one year before he died. By the time his life ended, he was known not only for the unique body of work he created, but also for his influence on the work of others. His philosophies were integral to the ideas of the Abstract Expressionists. And his aesthetic vision is considered to have been influential in the rise of Color Field Painting and Minimalism.

But equally important to the aesthetic legacy of the paintings, sculptures and prints that Adolph Gottlieb created in the course of his 70 years is the contribution he made to the larger artistic community to which he belonged—that which transcends formal advancements, generations and movements. Gottlieb had a vision of the artist as someone not separate from the rest of society, but intricately connected with it. He believed in the potential for art to transform civilization, and that it was important to discuss aesthetic ideas openly and in plain language so that it could be understood by all. He perceived that artists are essential to the ability a culture has to understand itself, and through his work he demonstrated the responsibility all artists have to express the madness, the chaos, the brilliance, the beauty, the darkness and the light of their time.

Featured image: Adolph Gottlieb -

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio