The Power of Steel in the Sculptures of the Late Alf Lechner

When he died on 27 February 2017, Alf Lechner was one of the most prolific sculptors in the world. Yet he was not widely known outside his native Germany. The reason for his relatively low profile is legendary. Lechner began painting as a child. He was talented enough that the acclaimed German landscape painter Alf Bachman noticed his abilities and took him under his tutelage. Although Lechner adored making art, he was suspicious of the art business. So for money he focused on his other passion: inventing. He started a business selling his inventions, and by the time he was 38, the company was valuable enough that he sold it. The sale earned Lechner enough money that he felt he could be an artist for the rest of his life without worrying about selling his work. Nonetheless, when he began exhibiting his work five years after selling his company, the German public reacted positively and Lechner ended up enjoying a long and lucrative career as a successful artist. Over the 60 years he was professionally active, he created more than 50 distinct series of steel sculptures, each expanding on his encyclopedic knowledge of his material and expressing his belief in the forces of simplicity and resistance.

The Man of Steel

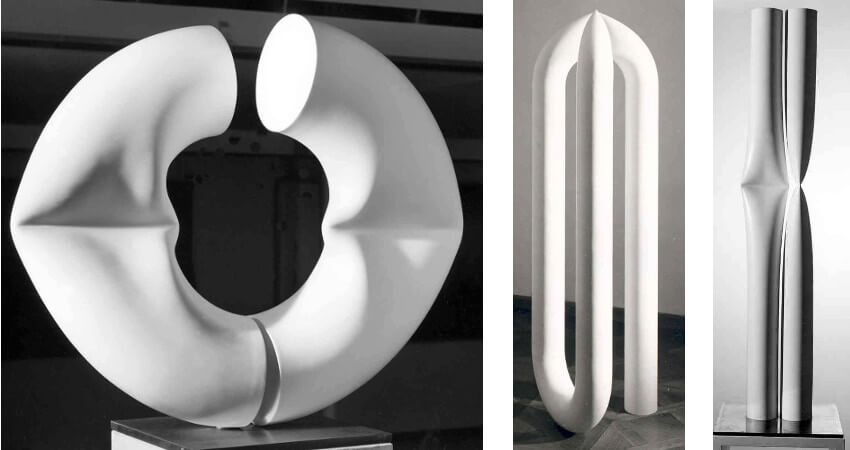

Alf Lechner held his first sculpture exhibition at Gallery Heseler in Munich in 1968, when he was 43 years old. Called Deformations, the show consisted of 17 sculptures made of steel. Lechner had first become interested in the properties of steel as an inventor, and had begun experimenting with it some years before selling his business. He was impressed by the contradictory properties of the material: that it is dense, heavy and strong, but that it can also be manipulated in an almost endless number of ways.

For the sculptures in his first exhibition, Lechner used white-coated steel tubing. Unlike solid steel bars, he could collapse the tubes easily, crushing them, bending them, and otherwise distorting their physical appearance. With each sculpture he attempted to achieve a precise and harmonious aesthetic statement of balance. All the work was done mentally ahead of time, as he imagined the guiding principles he wanted to express with each piece. The physical manipulation of the material was then conducted with minimum effort, in order to express the importance of simplicity.

Alf Lechner - Sculpture 108/1968 (left), Alf Lechner - Sculpture 102/1967 (middle), and Alf Lechner - Sculpture 111/1968 (right), as exhibited in the first Alf Lechner exhibition, © Lechner Museum

Alf Lechner - Sculpture 108/1968 (left), Alf Lechner - Sculpture 102/1967 (middle), and Alf Lechner - Sculpture 111/1968 (right), as exhibited in the first Alf Lechner exhibition, © Lechner Museum

Resistance

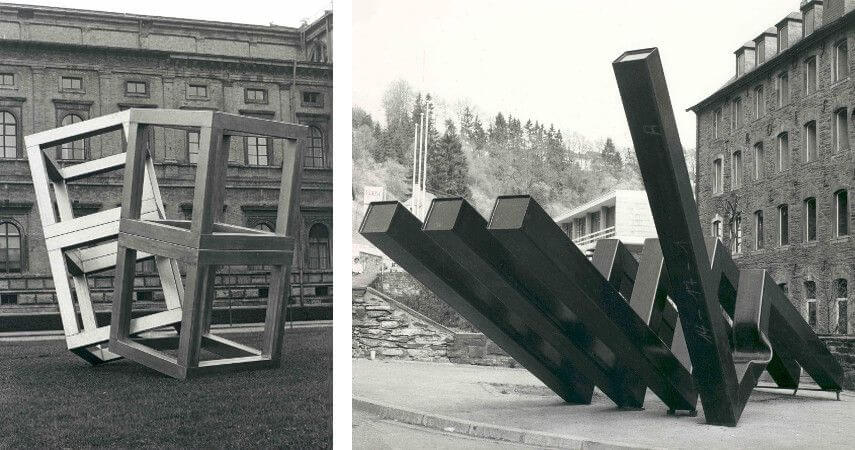

In addition to simplicity, Lechner was also concerned with the idea of resistance. He once said, “If it doesn’t show resistance, I’m not interested.” His fascination with resistance inhabited two simultaneous, yet different realms. The first is that of cooperative resistance. In that realm, the natural forces of the universe, such as magnetism or gravity, collaborate in a balanced show of harmony through their inherent tendency to resist each other. An example of how Lechner manifested this realm of resistance is his Sculpture 4/1973, which pits two steel forms against each other in such a way that they become stable through their resistance of each other.

The second realm of resistance is that of non-cooperation. This is the realm of divisiveness and incompatibility. Lechner manifested this realm of resistance through the use of visual non-conformity. For example, his public sculpture titled Mo / 184/1970, located in the western German City of Monschau, consists of three identical square steel tubes bent in an identical pattern, and a fourth tube, similar in appearance but differently deformed, which juts proudly upward from the other three. The individuality of the fourth form is a statement of resistance, in the socio-political sense of the word.

Alf Lechner - Sculpture 4/1973, Square stainless steel tube, ground (left) and Alf Lechner - Sculpture in public space Mo / 184/1970, Heavy-walled square steel tube (right), © Lechner Museum

Alf Lechner - Sculpture 4/1973, Square stainless steel tube, ground (left) and Alf Lechner - Sculpture in public space Mo / 184/1970, Heavy-walled square steel tube (right), © Lechner Museum

Material Limits

Lechner focused on geometric forms throughout most of his career. He made multiple forged-steel spheres, and worked frequently with triangles, wedges and rectangles. Most commonly he worked with squares or cubes, which he prized for their inherent objective qualities. Geometry expresses what most people consider to be the fundamental quality of steel: its stability. But as he matured in his understanding of steel, Lechner repeatedly found opportunities to express its complimentary opposite nature as well.

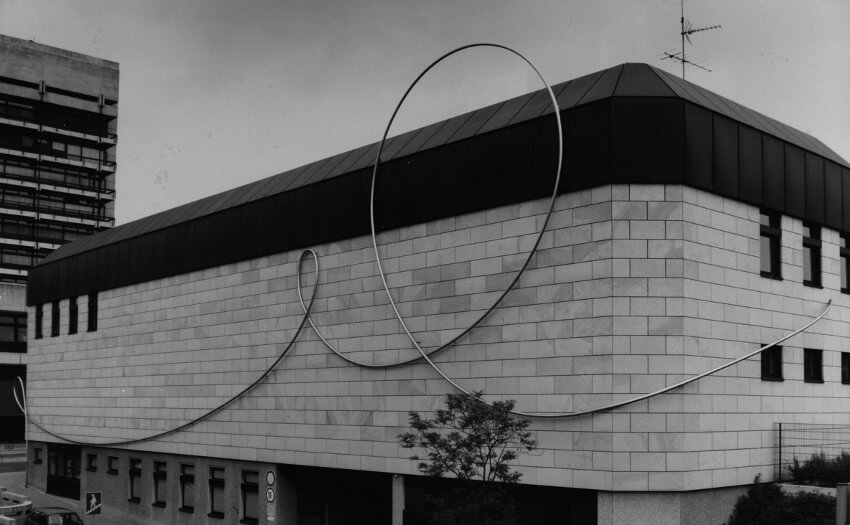

Indeed, steel is not as easy to manipulate as, say, aluminum. So most people would normally not choose steel for the construction of graceful, thin, flowing forms. But Lechner would find ways, as he said, to “undermine the limits” of his materials, pushing beyond what they were traditionally considered capable of achieving to create aesthetic statements that speak more to the least appreciated aspect of steel: its potential to yield.

Alf Lechner - Relief Relief, 1986, Federal Post Building, Bavaria, © Lechner Museum

Alf Lechner - Relief Relief, 1986, Federal Post Building, Bavaria, © Lechner Museum

The Lechner Museum

Another possible reason Lechner is not better known internationally has to do with a downside of working with solid, forged steel: it is difficult to find exhibition spaces capable of supporting the weight of the work. In the 1980s he addressed this issue in a whimsical way in a series called Sinking Bodies, which appeared to show his steel sculptures disappearing into the floor.

When it came time to construct the museum dedicated to his work, the Lechner Museum in Ingolstadt, Germany, the architects gave it the strongest gallery floors in the world, matched in their strength only by some floors in the Tate London. The floors are capable of supporting the physical weight of the monumental achievements Lechner left behind, leaving viewers the pleasure of simply enjoying the transcendent lightness of their being.

Alf Lechner - Sinking Bodies, 1984, solid forged steel, © Lechner Museum

Alf Lechner - Sinking Bodies, 1984, solid forged steel, © Lechner Museum

Featured image: Alf Lechner - Sculpture bridging, 1997, Forged steel, rolled and bent, © Lechner Museum

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio