On a Journey with Antoni Tàpies

When Antoni Tàpies died in 2012, he left a massive hole in the Spanish culture. He was easily the most influential Spanish visual artist of his generation, and in many respects it is hard to imagine the Post World War II Spanish avant-garde without him. In fact, it is even safe to say that without Tàpies, 20th Century art would have been quite different all across the globe. At a critical time in the history of his nation, Tàpies walked away from his comfortable bourgeois destiny and dedicated himself instead to forging an uncertain life as an artist. He was one of the six founders of Dau al Set, a tremendously influential avant-garde art collective that was active between 1948 and 1956. After leaving the group in 1952, Tàpies went on to create a visual language that bridged the most radical elements of Surrealism and Dada, with the fundamentals of formal abstraction and emergent global trends in informalism. Out of the roots of mysticism and metaphysics, he formed a universal aesthetic philosophy based on an appreciation for natural materials, and a connection to the Earth and its elements. His work culminated in what has come to be known as his “Matter Paintings”—artworks formed from, consisting of, and celebratory of the everyday found materials with which he found himself surrounded. Leaving behind a large collection of essays and lectures, he was eventually known as much for his philosophical outlook on art as for his work itself. He summed up his fundamental outlook on art and life in the statement, “Perfection cannot come simply from noble ideas, but should go together with a relationship to the earth.”

The Seventh Side

When the Spanish Civil War ended in 1939, the country transferred firmly into the hands of a Fascist, Nationalist regime. Led by General Francisco Franco, the regime preached that all elements of Spanish culture should be directed towards spreading and sustaining the political power of the government. Among other agendas, Franco advocated that all art be done in the style of fascist realism. He also outlawed the use of the Catalan language. This was agonizing to the generation of young artists who had grown up idolizing Spanish avant-garde giants like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and Salvador Dali. Fear quickly spread amongst young artists that modern Spanish culture was doomed. But at least six cultural revolutionaries had other plans. The Catalan poet Joan Brossa organized with Tàpies, Joan Ponç, Modest Cuixart, philosopher Arnau Puig, and an independent publisher named Joan-Josep Tharrats in 1948 to start a group that was intent on subverting the Nationalist agenda. They hoped to plant the seeds for a new, counter-Fascist avant-garde culture. In homage to their heroes the Surrealists and Dadaists, they named themselves Dau al Set—a term for the non-existent seven-side of a six-sided die.

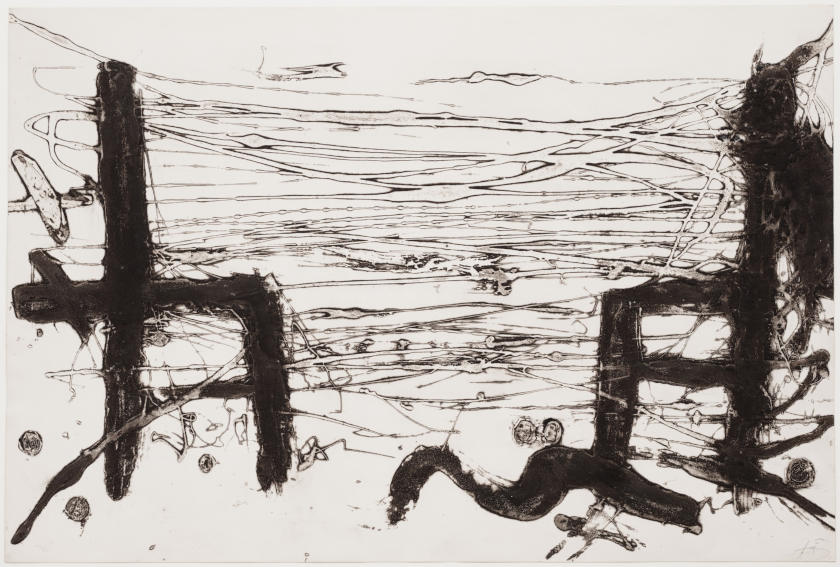

Antoni Tàpies - Chaises (Chairs), 1981. Carborundum. Composition: 36 1/4 x 54 3/4" (92 x 139 cm); Sheet: 36 5/8 x 54 3/4" (93 x 139 cm). Publisher: Galerie Lelong, Paris. Printer: Joan Barbarà, Barcelona. Edition 30. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Since the words were Catalan, the name Dau al Set was automatically controversial, and its quasi-mystical connotations signaled an embrace of the notion that elitist logic had only ever led the world into war. Dau al Set spread its ideas and its unique visual language by way of a magazine of the same name, published on the personal printing press of Tharrats. Its articles were also written in the outlawed Catalan language, and the images showed a mixture of mysticism, fantasy, and pure abstraction—all in direct opposition to the Fascist rule of Franco. Of the three artists in the group, Tàpies was the most abstract. He was self taught, his images were inspired by philosophy, and his methods were grounded in the pure joy of mediums and materials. He experimented by mixing unusual additives in with his oil paints, and soon started adding found materials and objects in with his paints. By 1952, he was so immersed in a quest to discover his own artistic path that he left Dau al Set. From that point onward, Tàpies devoted himself completely to informal abstraction and to the exploration of mixed media as an aesthetic position in its own right.

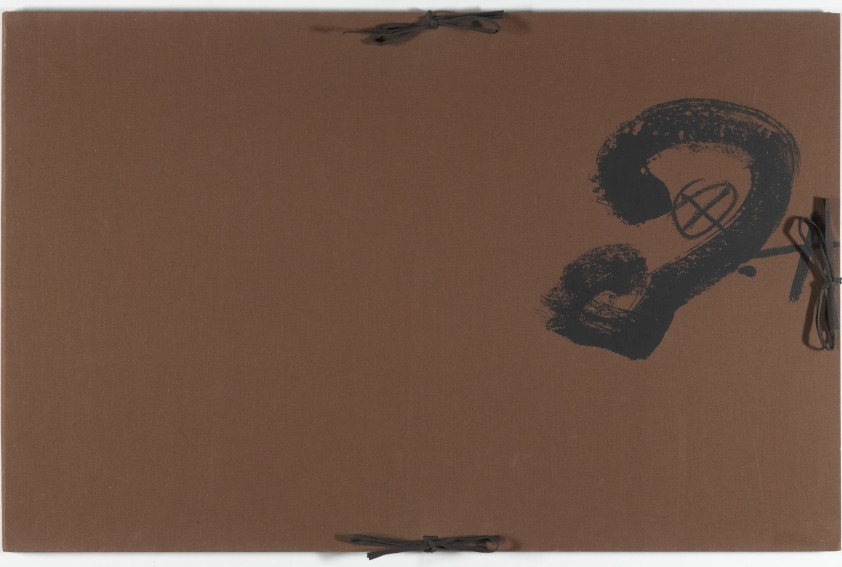

Antoni Tàpies - Petrificada Petrificante, 1978. 7 aquatints (including wrapper) with carborundum, collagraph, and/or aquatint, and 1 etching and carborundum; and supplementary suite. Irreg. page 20 1/2 x 16 1/8" (52 x 41 cm). Prints: various dimensions. Publisher: Maeght Éditeur, Paris. Printer: Atelier Morsang, Paris. Edition 195+. Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman Fund and gift of Galerie Maeght. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

The Matter of Painting

In addition to being a self-taught artist, Tàpies was a self-taught art theorist. It is in his writings, in fact, that we find much insight into the substance of his art. Two of his most revealing quotes are: “If I cannot change the world, I at least want to change the way people look at it;” and, “Profundity is not located in some remote, inaccessible place. It is rooted in everyday life.” We see both of these statements at play in works such as “Great Painting” (1958), a cardboard collage the color of dirt. The surface of the work looks charred, bruised, and stained. It is made from the simplest of materials, with the rawest techniques, by the hand of an artist with no formal aesthetic education. Yet, within the composition we encounter perfect balance, chromatic harmony, and a multitude of textures and hues. We would pass right by these materials on the street, but here our eyes can become lost in an exotic treasure map of endless depth and mystical scrawl.

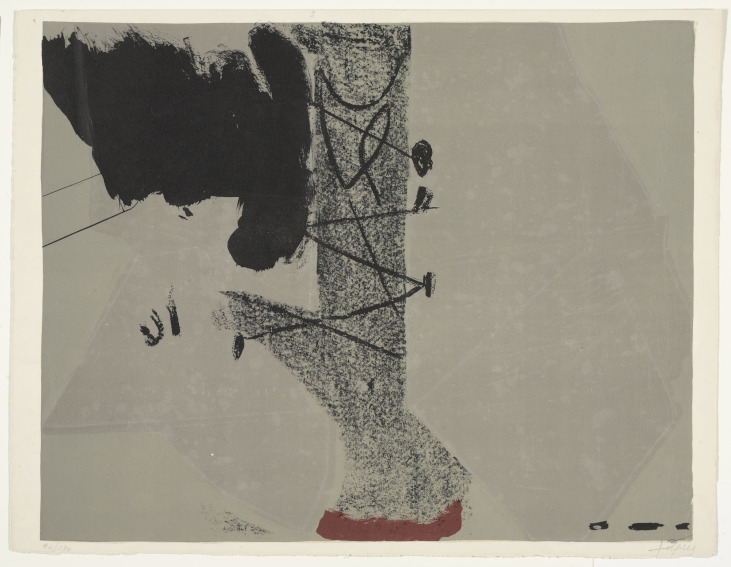

Antoni Tàpies- Saint Gall, 1962. Lithograph. Gift of Paul F. Walter. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Tàpies extended his thinking into the realm of sculpture, as well. One of his most famous pieces, “Desk with Straw” (1970), is as straightforward as its title indicates—it is an assemblage of an actual wooden desk covered with straw. The combination of materials seems nonsensical at first, and yet the perfect beautify of their juxtaposition lends the piece an aura of the inevitable, making it perfectly rational, not as furniture, but as art. Meanwhile, “Open Bed” (1986) takes the opposite approach. A full-sized, fire clay bed colored with enamel paint, the meaning of the form is in direct opposition to the materials. But it does not take long for a viewer to realize that the absurdity of sleeping on clay melts away if we think of the earth as our bed. As with all of the work Tàpies created, the profundity is right there, in the mundanity of everyday thought; it is all in how you look at it.

Featured image: Antoni Tàpies - Great Painting, 1958. Oil with sand on canvas. 78 1/2 x 103 inches (199.3 x 261.6 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © 2018 Fundació Antoni Tàpies/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio