Un Art Autre - Abstraction in Postwar Paris at Levy Gorvy

May 20, 2019

In 1952, the French art critic and curator Michel Tapié coined the phrase “Un Art Autre,” meaning “art of another kind,” to refer to a trend he perceived in abstract art away from rationality, and towards spontaneity. The trend was not only manifesting in France, where Tapié was based, yet it was to France that many artists from around the world traveled during the 1950s and 60s to share their exploration of this aesthetic phenomenon. Some were veterans of World War II who either stayed in Europe after the war or moved back there to study and work. Others were simply drawn to the excitement of a city and culture trying to rebuild itself. Taking advantage of the unique “café culture” of Paris, this international collective of artists and thinkers shared their ideas freely, creating a thrilling, primordial scene. That fascinating culture is currently the subject of an exhibition at Levy Gorvy in London, which takes its name from the movement to which Tapié gave a name. Un Art Autre features 22 paintings by five painters— Pierre Soulages, Zao Wou-Ki, Jean Paul Riopelle, Joan Mitchell, and Sam Francis—each of whom sometime during the 1950s and 60s called Paris home. Representing France, China, Canada and the United States respectively, these artists each brought with them an individualistic worldview and personal history. Each had a completely different relationship to painting, and to life. Yet, they all shared a desire to connect with something intuitive and free. By no means were these five artists the only voices of the “art of another kind” that evolved out of the Post War years in Europe, but seeing their works together in this exhibition does offer a poignant entry point into the movement of which they were part. It also gives contemporary viewers an opportunity to examine the differences between this movement and similar tendencies that manifested in other places during this time, such as Abstract Expressionism in the United States.

Color and Black and White

Today, Pierre Soulages is considered by many to be the greatest painter alive. He is beloved for his elegant, and often emotionally overpowering black paintings. Even when Soulages was first developing his unique voice in Paris after the war, he had a profound understanding of how the color black functioned in his paintings. He saw it not as a way to show darkness, but as a way to “create light.” By juxtaposing gloss and matte finishes, and creating relationships between black and white areas of the canvas, he created opportunities for the light to interact with the textures and hues. The relationships between the different areas of the canvas is part of what makes his paintings so luminous. In this exhibition, we see five of his canvases. Despite their tight compositional structure in paintings like “Peinture 195 x 130 cm, 3 février 1957” (1957) and “Peinture 195 x 155 cm, 7 février 1957” (1957), their vibrant blacks and forceful brush strokes bring their surfaces to life. They are anything but pure black, but the interplay of the ochres, blues and whites somehow make the black shine all the more.

Joan Mitchell - Untitled, 1957. Oil on canvas. 69 x 58 1/2 inches (175.2 x 148.5 cm). Private Collection, Santa Barbara. © Estate of Joan Mitchell.

Color relationships were also of paramount importance to Joan Mitchel, four of whose works are in this exhibition. All four—which will likely be new to most visitors, as they were assembled from entirely from private collections—demonstrate the masterful ability Mitchell had to convey emotional tone through her color palette. What we are seeing in her works is clearly something “of nature,” despite the pictures being completely abstract. That sense of nature-ness is only heightened by the almost ecstatic gestural style Mitchell developed during her frequent visits, and eventual move to France—a style that is beautifully represented by the works in this show. Her compositions are the loosest and freest feeling of any of the works in the exhibition: a testament to her desire to disappear inside herself while painting, and to capture a sense of something personal based on her own memories of the natural world.

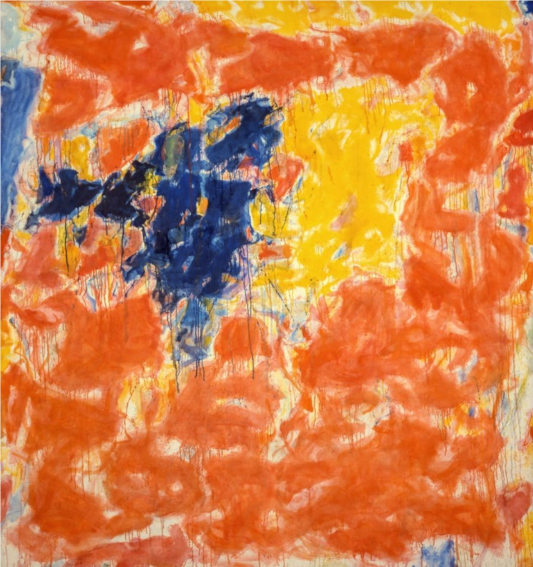

Sam Francis - Arcueil, 1956/58. Oil on canvas. 80 3/4 x 76 inches (205.1 x 193 cm). Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard K. Weil, 1962. © Sam Francis Foundation, California / DACS 2019.

The Full Range of Impulse

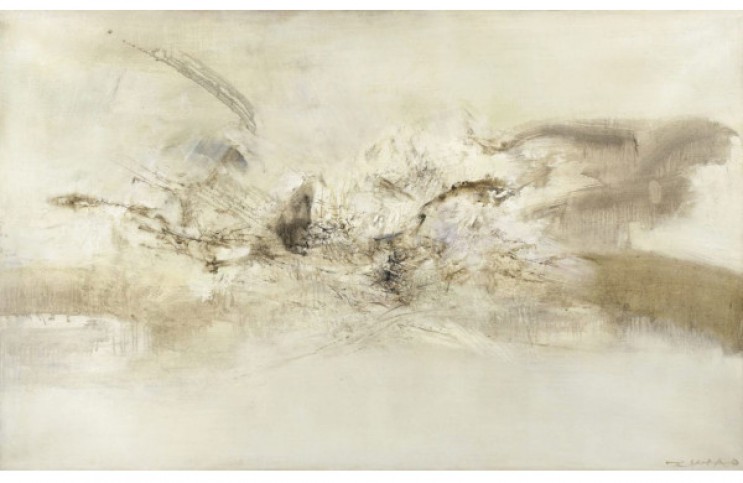

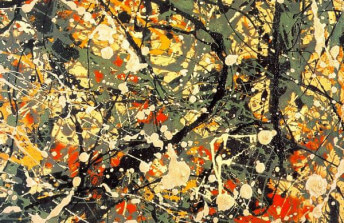

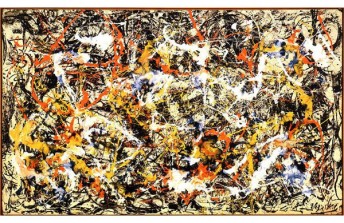

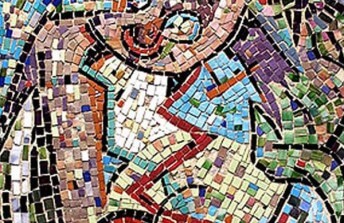

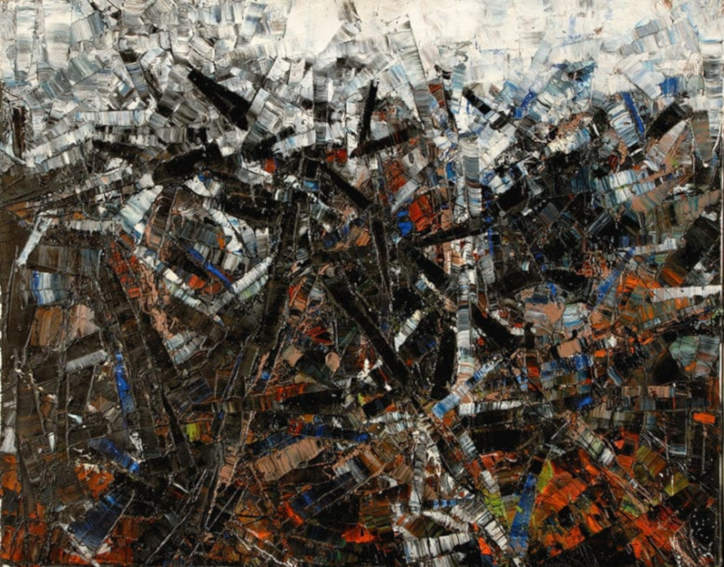

The works on view by Jean Paul Riopelle demonstrate the dramatic change that occurred in his methods during the early 1950s. The most recognizable in the show is “Abstraction (Orange)” (1952). One of the larger works in the show, its frenetic gestural action draws an immediate parallel to the splatter paintings most often associated with Abstract Expressionist painters like Jackson Pollock. In later works like “Horizontal, Black and White” (1955), we see Riopelle constructing a far more deliberate technique, with tight, measured, anxiety-filled brush marks, while nonetheless retaining the impulsive energy that so enlivens his work. On almost the opposite end of the impulse scale we see three sublime paintings by Zao Wou-Ki. Their muted palettes and balanced compositional harmonies show a painter who strikes a wonderfully haunting balance between free expression and measured calm.

Jean Paul Riopelle - Horizontal, Black and White, 1955. Oil on canvas. 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 inches (73 x 92 cm). Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen. Henie Onstad Kunstsenter Collection, Høvikodden, Norway. © SODRAC, Montreal and DACS, London, 2019.

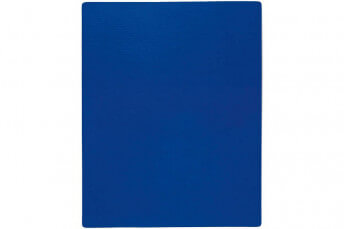

The painter I am least familiar with from this exhibition is Sam Francis. After seeing the five examples of his work in the show, I feel there is much more to learn about him still. The ethereal frivolity of an untitled, orange, yellow and blue composition evoked in me thoughts of Hellen Frankenthaler, while his “Blue Series No. 1” (1960) harkened immediately to Yves Klein. Two other pieces—“Composition” (c. 1957-58) and “Untitled” (1959)—offered something more distinct: an almost electrical excitement, as if I was literally looking at pictures of fluctuation and flow. Those concepts, in fact, are at the heart of what this exhibition has to say about the “other kind of art” that emerged in Paris in the 1950s and 60s. It is hard to pin down exactly, and hard to name, but it was an art defined by its ability to change, and its willingness to let go. Un Art Autre is on view at Levy Gorvy London through 5 July 2019.

Featured image: Zao Wou-Ki - 16.09.69, 1969. Oil on canvas. 31 7/8 x 51 3/16 inches (81 x 130 cm). Private Collection. © DACS 2019.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio