The Story Behind Jackson Pollock’s Only Mosaic

Most art lovers know who Jackson Pollock was. As one of a handful of bonafide celebrity painters, Pollock is a name even non-art lovers recognize. Though as famous as the Abstract Expressionist pioneer became in the 50s, relatively little is known about his earlier work. Happily, a Jackson Pollock mosaic currently on view in New York offers Pollock fans an exciting glimpse of his proto-Abstract Expressionist days. The WPA (Save the NEA) is the inaugural show at the new Chelsea location of the Washburn Gallery, formerly of West 57th Street. It showcases works created as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) by artists who at the time were flat broke, but who later went on to become legends of American art. It includes works by Lee Krasner, Ilya Bolotowsky, David Smith, Stuart Davis, Reuben Kadish, and of course Jackson Pollock. The show is intended to highlight the impact the WPA made on the American art scene, and the legacy of civic art appreciation the program established in the United States. The timing of the exhibition is political. The Trump administration recently promised to defund the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The hope of gallery founder Joan Washburn is that this exhibition will inspire viewers to take action in it defense.

A Brief History of the WPA

In the years following the global stock market crash of 1929, the unemployment rate in the United States skyrocketed. By the early 1930s it hit 25 per cent. Tens of thousands of people were starving and homeless, and there seemed to be no recovery in sight. When Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected President in 1933, putting people back to work was his priority. By 1935, the Roosevelt administration would institute the so-called New Deal, a sweeping government intervention that would put throngs of unemployed people back to work doing literally anything that needed to be done anywhere in the country: drought relief, parks services, infrastructure building, construction—the list went on and on. The Works Project Administration, or WPA, was the most substantial part of the New Deal, and was mainly aimed at hiring unskilled workers to do public works projects.

David Smith - Untitled (Bathers), 1934, oil on canvas, 17 1/4 x 16 in., Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth, (c) The Estate of David Smith, licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

David Smith - Untitled (Bathers), 1934, oil on canvas, 17 1/4 x 16 in., Courtesy The Estate of David Smith and Hauser & Wirth, (c) The Estate of David Smith, licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

But more than a year before the New Deal rolled out, a lesser known project was initiated called the PWAP, or Public Works of Art Project. The PWAP came out of discussions that were taking place within the Roosevelt administration about whether to help unemployed artists. Since artists were not considered traditional workers, and so many of them tended to spend most of their lives in a state of semi-unemployment anyway, many argued they were not in need of any extraordinary government assistance. But Harry Hopkins, a close advisor to President Roosevelt, allegedly ended the debate by pointing out the obvious, saying, “Hell, [artists] have got to eat just like other people.” In its first year, the PWAP hired thousands of professional artists to make paintings and sculptures for public buildings. As evidenced by an exhibition at the Smithsonian in 2009 of PWAP artists, most of them never went on to have any type of influential career afterward. But one name from the PWAP ranks is also familiar from the current exhibition at Washburn Gallery: Ilya Bolotowsky.

Ilya Bolotowsky - Mural for Williamsburg Housing Project (1980) full-scale reconstruction. Courtesy of Washburn Gallery

Ilya Bolotowsky - Mural for Williamsburg Housing Project (1980) full-scale reconstruction. Courtesy of Washburn Gallery

Abstraction and the WPA

Ilya Bolotowsky is recognized today as one of the leading American abstract artists of the 20th Century. But when he was hired for the PWAP, he made figurative paintings. That was likely because the only directive from the project administrators in regards to subject matter for PWAP artists was to make works about “the American scene.” But just a couple of years later, the WPA would replace the PWAP with something called the Federal Arts Project (FAP), which would expand the scope of the work government-hired artists were doing. One of the administrators hired for the mural portion of the FAP happened to be an abstract artist named Burgoyne Diller. Against the opposition of his colleagues, Diller advocated for abstraction to be accepted as part of the visual lexicon of the project. Because of his advocacy artists like those included in the current exhibition at Washburn Gallery, as well as Mark Rothko, William Baziotes, Willem de Kooning and hundreds of others, were given WPA jobs.

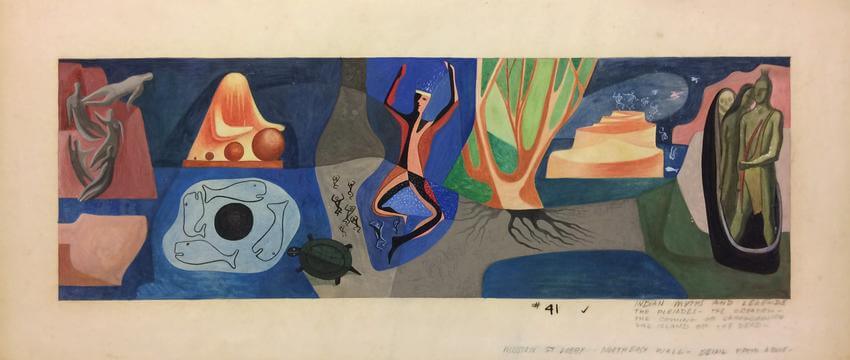

Reuben Kadish - Untitled (Mural Study), Graphite and gouache on paper, 10 3/4 x 24 1/2 in.

Reuben Kadish - Untitled (Mural Study), Graphite and gouache on paper, 10 3/4 x 24 1/2 in.

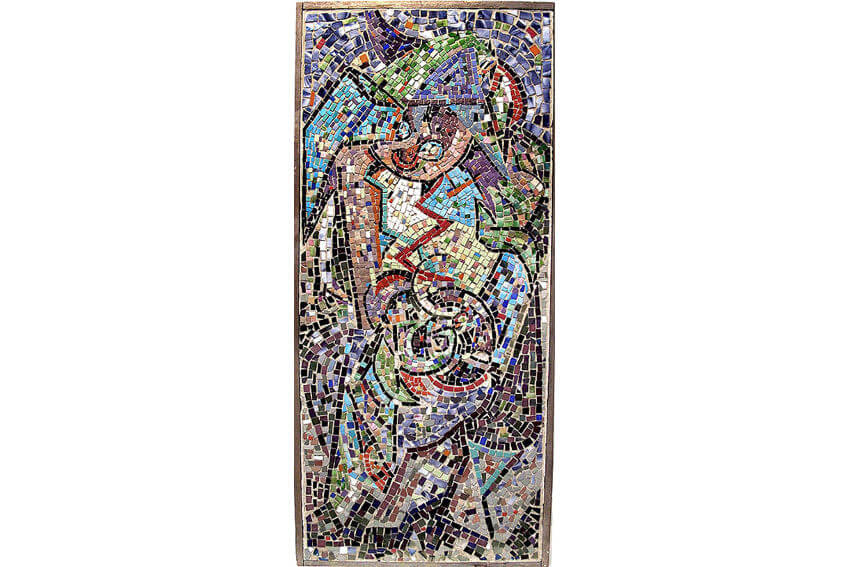

The mysterious Jackson Pollock mosaic currently on view at the Washburn Gallery has a murky history. It was created by Pollock as a proposal for the WPA, but was rejected. It is unclear whether the piece as it exists today was intended to be the finished work, or if it was a model for something much larger. Regardless, its existence brings to mind other questions. For example, it obviously speaks to the willingness Pollock had to experiment with new methods and styles. If he had not been hired by the WPA, and not had the luxury of a steady income during the depression, would he have still had that experimental attitude? Or would he have succumbed to market pressures? That raises the much bigger question of what the American Post War art landscape would have looked like in general if FAP had not existed. Would any of the biggest names we know from that era have risen to the top? Or would they have been replaced by other names, other styles, and perhaps even more interesting work? Obviously, The WPA (Save the NEA), based on its subtitle, is intended to express the opinion that it is the proper role of the government to support the arts. But others might see the WPA as representative of a time when cultural winners and losers were picked, and the deck was stacked in favor of the weak. It is a fascinating question to contemplate. And in any case, this exhibition offers a rare look back at some of the earliest artworks created by artists who would later become some of the most influential figures in 20th Century abstract art.

Jackson Pollock’s only mosaic - Untitled CR1048 (c. 1938-41), created for and rejected by the WPA. Courtesy of Washburn Gallery/Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS

Jackson Pollock’s only mosaic - Untitled CR1048 (c. 1938-41), created for and rejected by the WPA. Courtesy of Washburn Gallery/Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS

Featured image: Jackson Pollock's only mosaic - Untitled CR1048 (c. 1938-41), created for and rejected by the WPA (detail). Courtesy of Washburn Gallery/Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio