Gagosian Paris Gathers Artists Who Create Art Blanc sur Blanc

Jan 30, 2020

An exhibition at Gagosian Paris titled Blanc sur Blanc (White on White) has once again ignited the timeless debate about the validity of all-white art. This conversation goes back at least as far as 1918, when Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, the founder of Suprematism, debuted his painting “White on White”—an image of a tilted white square on a white background. Malevich was already infamous for the “Black Square” painting he revealed three years earlier in The Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10. However, “White Square” took the outrage to the next level by not only challenging the value of subject matter in art, but also challenging the value of hue. In the wake of Malevich, countless other artists have made all-white artworks: from the Minimalist “White Painting (Three Panel)” (1951) of Robert Rauschenberg (who said “a canvas is never empty”); to the brutish, quasi-figurative all-white sculptures of Cy Twombly; to the sparse, Post-Atomic glow of “Untitled (Electric Light)” (2019), a white light sculpture by Mary Corse. Art collectors believe firmly in the cultural and financial value of all-white art, as evidenced by at least two recent auction results: “Bridge” (1980), an all-white painting by Robert Ryman that sold at Christie’s for more than $20 million (US) in 2015, and “21 Feuilles Blanches” (1953), an all-white mobile by Alexander Calder that fetched $17.9 million (US) in 2018 (more than twice its high estimate). Yet, to people outside the art field, white-on-white art can be infuriating. Perhaps the genius of the current Gagosian exhibition is that it does not simply show the public a single all-white artwork, nor a selection of all-white works by a single artist. Instead, it brings together works by 27 artists, spanning a wide range of time periods, movements, mediums, intentions, and personal backgrounds. Seeing so many white artworks in one place at one time reveals the nuanced truth that so many haters fail to admit: there really is no such thing as plain white.

White as a Manifesto

Among the works on view in Blanc sur Blanc is an all-white slashed canvas by the Italian artist Lucio Fontana. In the press materials for the show, Gagosian refers to an essay Fontana published in 1946 called the Manifesto Blanco (White Manifesto). Although a bit ranty, this essay can provide some guidance for viewers who doubt the value of monochromatic painting. Contrary to what its title suggests, however, the White Manifesto never actually mentions the color white. Rather, it speaks of the need for a new art, “free of all aesthetic artifice.” For Fontana, the purity of the color white was symbolic of this new starting point. The White Manifesto calls on artists to focus on “color, the element of space; sound, the element of time; and movement, which develops in time and space,” a strategy that Fontana insists will result in work that draws “closer to nature than ever before in the history of art.”

Installation view. Artwork, left to right: © Foundation Lucio Fontana, Milano / by SIAE / ADAGP, Paris, 2020; © Cy Twombly Foundation; © Imi Knoebel / ADAGP, Paris, 2020. Photo: Thomas Lannes

The notions expressed in the White Manifesto formed the basis of Spatialism, the movement Fontana founded the following year. Over the course of two decades, Fontana elucidated the core elements of Spatialism through two groundbreaking series of works. The first was his “Environments” series—15 light sculptures now considered to have been the first examples of installation art. Each “Environment” was basically a custom-built room lit by a single color of light. Whether white, black, red, blue, green, or whatever, Fontana felt the amalgamation of a single color with an otherwise empty space embodied the essence of his ideas. The second series of works Fontana made to illustrate the concepts of Spatialism was his now-iconic series of slashed canvases—monochromatic surfaces slashed by a knife. The slashes were not simply expressions of drama, however. They created literal entryways into a world of movement, color and space. Each slash pulls the viewer into an active role, drawing us inward by revealing a glimpse into the space behind the painting. By making that never-before utilized part of the painting a key aspect of its subject matter, Fontana concocted something kinetic and mysterious. Looking back at his “Environments,” it is clear to see how these slashed canvases expressed the same ideas, just on a different scale.

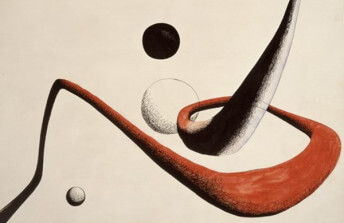

Jean Arp - The friend of the little finger, 1963. Plaster, 4 x 9 1/2 x 5 1/8 inches (10 x 24 x 13 cm). © ADAGP, Paris, 2020

The Broadening of Perspective

Like the slashed canvases of Fontana, every one of the works featured in Blanc sur Blanc is more complex than it might seem at first. Three yarn sculptures by Sheila Hicks illustrate how fragile the idea of pure color really is, as texture and mass play havoc with the light. A sculpture by Rachel Whiteread, meanwhile, takes what at first seems like a random assortment of white construction materials leaned against a wall, transforming it into a scene of visual and emotional clarity. These types of material accumulations in space have become such a ubiquitous part of the everyday urban environment, but in this case, not only does Whiteread demonstrate the inherent aesthetic presence of her materials, she also expands our understanding of the definition of color.

Installation view. Artwork, left to right: © Enrico Castellani / ADAGP, Paris, 2020; © Atelier Sheila Hicks. Photo: Thomas Lannes

Ultimately, perhaps, that is what white on white art has always been about—the broadening of perspectives. Are we able to look at something so simple, so Minimalist, and so direct without feeling insulted, as if the artist is just daring us to call it too easy? Are we capable of acknowledging the magic of white on white art in the same way as we embrace the simple sound of a gong, the nuanced flicker of a candle, or the gentle tickle of a feather? Can something so slight carry powerful emotion? This question has been asked many times, and it will not end with this current exhibition, because there will always be artists who know there is nothing plain about white on white, and who will always feel compelled to return to it as the zero point of art.

Featured image: Installation view. Artwork, left to right: Archives Simon Hantai / ADAGP, Paris; © Rachel Whiteread. Photo: Thomas Lannes

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio