Reinterpreting Collage - Brenna Youngblood

Jun 7, 2017

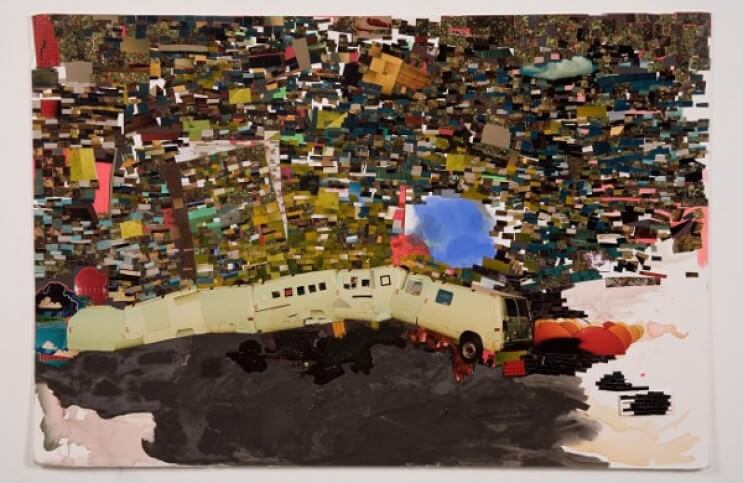

If, like many art lovers, you constantly carry with you the baggage of having looked at tens of thousands of images of art in your life, you might, when glancing quickly over the work of Brenna Youngblood, find yourself referencing the names of other artists from the past who made work of a seemingly similar aesthetic nature. For example, Robert Rauschenberg immediately comes to mind when looking at the multi-media collage Untitled (Double Lincoln), made by Youngblood in 2008. Or the 2015 Youngblood painting Democratic Dollar might evoke the abstract use of rough hewn iconography made famous by Jasper Johns. Or the Dadaist Hannah Höch might spring into your consciousness when looking at the Youngblood painting Foreva, from 2005. Or finally the name Arman, that pioneer of the art of accumulation, might pop up when looking at the 2005 Youngblood painting The Army. Undeniably, each of these works owes some aesthetic dept to artists of the past. But also each of these works stands confidently on its own. All of those other artists mentioned above came to the techniques of collage, assemblage, and accumulation and the use of found objects for reasons that had to do with their own times. Youngblood may sometimes utilize their techniques, and as a result create imagery that summons their ghosts, but her work belongs to the now.

Collage as Longhand

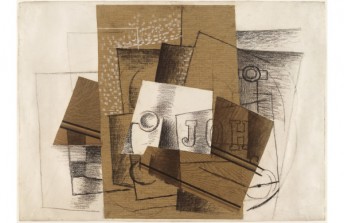

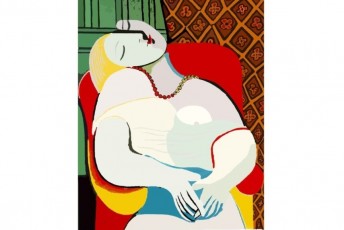

When collage was first used in fine art by the Cubist pioneers Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, it created a form of super-realism by introducing actual materials and objects from the physical world to the surface of artworks, thereby mixing in a previously unheard of way the illusionary and concrete. It also created a sort of aesthetic shorthand, one that was later extended by Dada artists like Hannah Höch and Francis Picabia, who used collage to create an instantaneous expression of absurdity. When Robert Rauschenberg then even later turned to collage, he did so to explore the abstract possibilities of iconic images, mixing them in ways that question the meaning of recognizable reality. Each of these artists used collage slightly differently, but each also had in common the idea that collage served as a way to say a lot with a little.

Brenna Youngblood uses collage in a subtly different way. Her use of photographs and found objects on the surfaces of her paintings results not so much in shorthand, but rather in a sort of longhand. She employs collage and assemblage in ways that expand the depths of her images, and increase their potential narrative depth. Her collages lack the acrid sarcasm of Dada. They avoid the conceptual, academic inquisitiveness of artists like Rauschenberg. They have something perhaps in common with the works of Picasso and Braque in that they seem to be striving to reveal a heightened reality. But the reality that Youngblood expresses in her collages is a more visceral, raw, personal, intuitive reality than the early Modernist reality investigated by Picasso and Braque. It is a reality with no clear sense of direction or morality, and no clear sense of potential. It is still unfolding. Rather than critiquing it, defining it or explaining it, through her collage and assemblage longhand Youngblood sumptuously adds to it with layers of richness, mystery and scope.

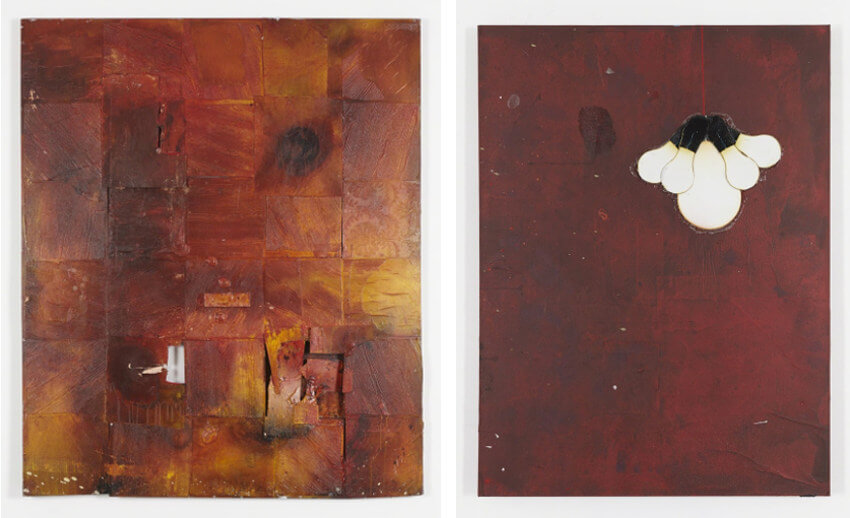

Brenna Youngblood - Chuck Taylor, 2015, Color photograph and acrylic on canvas, 72 × 60 in, (Left) and X, 2015, Paper and acrylic on canvas, 72 × 60 in, (Right), photo credits of the artist and Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, California

Brenna Youngblood - Chuck Taylor, 2015, Color photograph and acrylic on canvas, 72 × 60 in, (Left) and X, 2015, Paper and acrylic on canvas, 72 × 60 in, (Right), photo credits of the artist and Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles, California

Surface as Image

In recent years, Brenna Youngblood has been relying less on collage and assemblage, turning more to paint in the creation of layered fields of colors and textures. Her most recent paintings are profoundly atmospheric, even moody at times. They are dynamic, confident visual objects. Some of them can almost be read as monochromatic color fields, perhaps similar in certain aspects to the works of the Color Field artists of the 1960s and 70s. But whereas the works of such artists invite contemplation, often serving as the beginning point of a transcendent mental experience, these scraped, rustic, worn and weathered surfaces of Youngblood are more easily read as aesthetic ends in themselves.

Youngblood paints and scrapes and paints and scrapes, adding layer upon layer of hue; mixing worn down and impasto textures in ways that converse effortlessly with the contemporary manufactured world. They are surface images. They are ends in themselves. Whether they make statements or pose questions is indiscernible, and perhaps irrelevant. Like visual slices of life they contain all the complexity and confusion of the culture they reflect. Looking at these surface images feels voyeuristic, almost fetishistic. Youngblood is painting our time without judgment, in ways that are simultaneously nightmarish and beautiful.

Brenna Youngblood - Division, 2017, Wallpaper, acrylic paint and spray paint on found wood, 71 3/10 × 60 × 1 3/5 in (Left) and Untitled (red room), 2017, Photographs and acrylic paint on canvas, 40 1/5 × 29 9/10 × 1 3/5 in, photo credits of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels

Brenna Youngblood - Division, 2017, Wallpaper, acrylic paint and spray paint on found wood, 71 3/10 × 60 × 1 3/5 in (Left) and Untitled (red room), 2017, Photographs and acrylic paint on canvas, 40 1/5 × 29 9/10 × 1 3/5 in, photo credits of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels

Vision and Revelation

The longer I look at the works of Brenna Youngblood, the less I associate them with the tens of thousands of images of other artworks I have seen in my life; and the more deeply I consider them, the less they remind me of those who have used similar techniques in the past. The closer I look, the more rewards I am provided by what I see. I would not call Youngblood a visionary, because I feel too much when I see her work like she is restlessly searching for something. She is not clear in her vision, though her individual works do have clarity. But I would also not follow the other art writers who have rushed to compare her with her predecessors by focusing only on formalities like materials and technique.

What strikes me most about the total body of work so far made by Brenna Youngblood, an artist hopefully still quite early in her career, is not what it reveals, but rather that is so clearly has the potential to one day be revelatory. Youngblood possesses an earnestness that invites truth. Her paintings, sculptures and installations each represent some individual attempt she has made to grasp for something real. Oftenshe has managed what so often seems impossible: authenticity; and equally as often she has taken hold of something genuinejust long enough to give the rest of us a glimpse.

Brenna Youngblood - Untitled (subtraction sign), 2011, Tree, 3 × 21 × 3 in, photo credits of the artist and the Landing, Los Angeles

Brenna Youngblood - Untitled (subtraction sign), 2011, Tree, 3 × 21 × 3 in, photo credits of the artist and the Landing, Los Angeles

Featured image: Brenna Youngblood - The Army, 2005, photo credits of the artist and Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, California

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio