A Fine Relationship between Calligraphy and Abstraction

Calligraphy is where symbol and gesture meet. At its core, calligraphy is writing. It utilizes the traditional tools of the writer: pen and ink, or brush and paint. But the objective of writing is to communicate predetermined meanings through standard forms of language. The calligrapher does not simply write words to communicate a fixed thought. The calligrapher uses the pen or the brush as an extension of the whole body, and the whole spirit. The calligraphic mark should convey something metaphysical as well as physical. The spirit should inform the body, which should move in a unified gesture, transferring the energy of both body and spirit into the arm, into the hand, into the pen and finally into the mark. Calligraphy has existed for thousands of years, manifesting independently in multiple cultures across the globe. Such devout respect is given to calligraphy in some cultures that a direct connection is made between calligraphic writing and the power of the divine. With its tradition of conveying meaning beyond the objective into the realm of the unknown, it is no wonder then that calligraphy has appealed to so many abstract artists, especially those concerned with the communicative power of gesture and line.

Ancient Meaning and Gesture

A simplistic way to think about calligraphy is that it is a form of highly decorative writing. Many calligraphers in fact specialize in particular fancy type styles that evoke Old English writing, ancient Latin writing, Arabic writing, or Eastern Asian writing. But the spirit behind calligraphic gestures is not to simply copy some existing typeface or font. That would be the realm of typography, writing letters that might be decorative but that can be easily read. Calligraphy is more about individual gestures, and the meaning that can be expressed in writing beyond what is inherent in the symbols themselves.

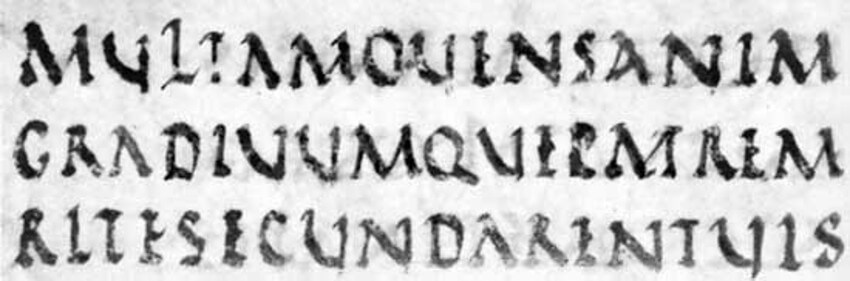

4th Century Latin calligraphy from a copy of Virgil’s Aeneid, photo courtesy Vatican Library

4th Century Latin calligraphy from a copy of Virgil’s Aeneid, photo courtesy Vatican Library

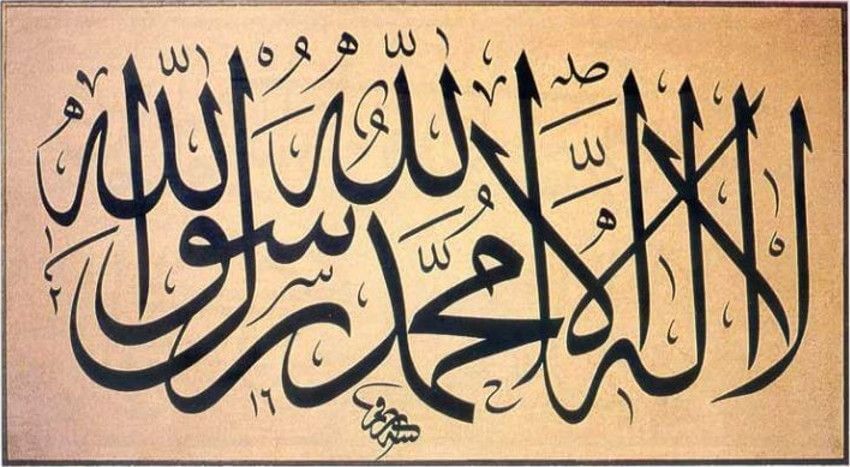

To what extent a calligraphic tradition attempts to express the unknown depends on the culture from which it originated. Ancient Latin calligraphy is more like a traditional script than an expressive form of art. But each letter in Latin calligraphy nonetheless contains a serif, or a small, expressive line attached to the ends of the symbols. The serif is created by quick a physical gesture, lifting the tip of the pen off the page. In the serif can be found the subtle but important personal expression of the calligrapher. Compare that subtlety to the expressive flair of Arabic calligraphy. The most dramatic looking of the five distinct forms of Arabic calligraphy is Thuluth, a name that roughly translates into “thirds,” relating to the proportions of the written symbols. The greatest artist associated with Thuluth was Mustafa Râkim (1757–1826), whose calligraphic creations achieved what is considered the proportional ideal, showing great precision while also expressing maximum energy.

Example of the Thuluth style of Arabic calligraphy by Mustafa Rakim

Example of the Thuluth style of Arabic calligraphy by Mustafa Rakim

Gestural Abstraction

Based on its ancient traditions, it is natural that the calligraphic tradition should hold relevance to abstract artists. From the beginning of abstraction, at least in the Western tradition, there have been two complementary, yet distinct tendencies that have repeatedly manifested in the work of many abstract artists. One tendency is toward the precise: geometric abstraction, grids, mathematical patterns, and so on. The other tendency is toward the free: impulsive marks, intuitive gestures, subconscious writing, biomorphic forms, etc. Calligraphy inhabits a space that incorporates both. It is system based, and yet it invites intuition, impulsivity, and subconscious intervention.

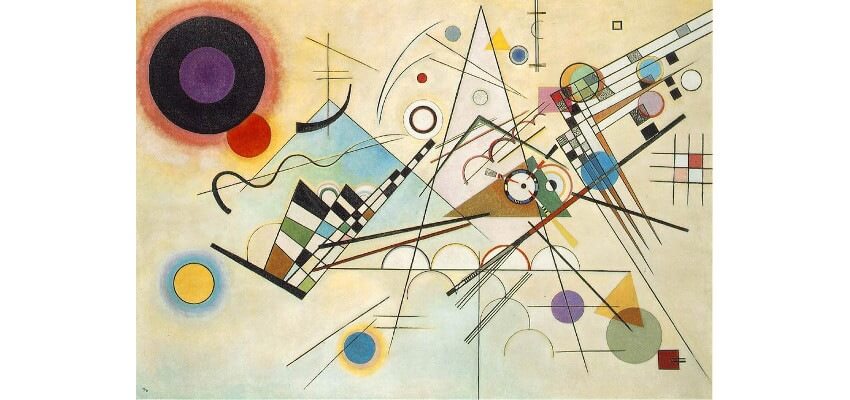

Many of the abstract paintings of Wassily Kandinsky are, in a sense, the perfect expression of the calligraphic spirit. They are sometimes referred to as geometric abstraction, due to their inclusion of universal geometric shapes and forms. They are also sometimes referred to as lyrical abstraction and gestural abstraction thanks to their use of spontaneous, free, biomorphic lines. Many of their curves and markings correlate to those seen in ancient calligraphy, especially from East Asian and Arabic traditions. Their geometric elements express stability and control, while their gestural, lyrical elements express the energy of the unknown, and the dynamism of the human spirit.

Wassily Kandinsky - Transverse Line, 1923, Oil on canvas, 55.1 × 78.7 in, 140.0 × 200.0 cm © Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany

Wassily Kandinsky - Transverse Line, 1923, Oil on canvas, 55.1 × 78.7 in, 140.0 × 200.0 cm © Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany

Calligraphy and the Abstract Expressionists

After World War II, the idea of forming a deeper connection with the interior self was of monumental concern for many artists. In particular, the artists associated with Abstract Expressionism were interested in investigating any type of philosophy or tradition that might enable them to express themselves in a deeper, more intuitive, more honest way. The traditions of calligraphy informed much of the work made by these artists, as it provided a framework for bringing physicality, emotion, spirit and the ancient mind together in the expression of physical mark.

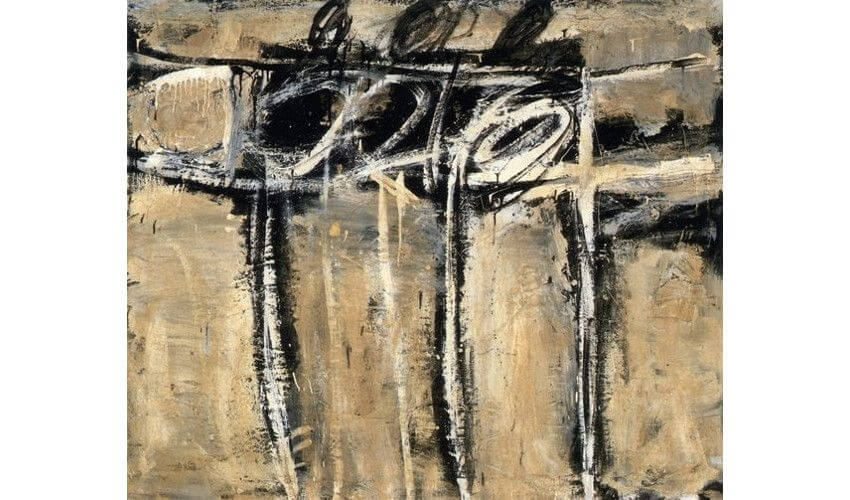

Franz Kline stood out as the Abstract Expressionist painter most directly inspired by calligraphy. He is known for making innumerable sketches of his subjects in black ink on telephone book pages. The sketches were done quickly in ink, and resembled in many ways the kanji of East Asian calligraphy. According to legend, his friend, the painter Willem de Kooning enlarged one of his small drawings in a projector. When Kline saw the power of the enlarged marks he understood the inherent energy and communicative potential of the calligraphic mark. His marks no longer had to relate to subject matter; they could become emotive forces in themselves. Kline worked large from that point on, making grand pictures of marks that seem to have been quickly made, but that were, in fact, the result of a long, deliberate process. His ability to convey the energy of a calligraphic mark through a laborious process remains one of the most stunning accomplishments of his career.

Franz Kline - Mahoning, 1956, Oil and paper on canvas, 80 3/8 × 100 1/2 in, 204.2 × 255.3 cm, Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of Art © Franz Kline, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Franz Kline - Mahoning, 1956, Oil and paper on canvas, 80 3/8 × 100 1/2 in, 204.2 × 255.3 cm, Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of Art © Franz Kline, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Mythical Writing

Many other abstract artists have found, and continue to find, innovative ways to break down elemental calligraphic techniques in order to create new forms of mythical writing. Using gesture, line, energy and patterns they create new visual languages capable of evoking and conveying a range of emotional states. Here are some of our favorites:

Cy Twombly - Untitled I (Bacchus), 2005, Acrylic on canvas, © Cy Twombly

Cy Twombly - Untitled I (Bacchus), 2005, Acrylic on canvas, © Cy Twombly

Cy Twombly

American painter Cy Twombly used the tradition of calligraphy to deconstruct the image making potential of writing. His paintings used the written line to create communicative images that sometimes seem to be part scribble and part kanji, but that are all gesture and emotion. Early in his exploration of this technique he focused more on the symbolic nature of his marks, creating structured compositions. As he became freer and more experimental he allowed the calligraphic impulse to manifest in a more abstract cursive style, what has become known as his iconic “scrawl.”

Cy Twombly - Untitled, 1951, Acrylic on canvas, © Cy Twombly

Cy Twombly - Untitled, 1951, Acrylic on canvas, © Cy Twombly

Brice Marden

Already famous by the mid-1970s as a painter of monochromes, Brice Marden reinvented his aesthetic after becoming acquainted with the Chinese calligraphic writing on poem scrolls. In a series called the Cold Mountain Paintings, Marden created intuitive calligraphic columns of abstract symbols. A Chinese monk named Hanshan and his 9th Century Cold Mountain Poems inspired the aesthetic approach. The paintings, like the poems, are expressions of freedom, instinct, a connection to nature, and the beauty of harmonious systems.

Melissa Meyer

Third generation Abstract Expressionist Melissa Meyer incorporates the spirit and the aesthetic of calligraphy in her compositions, which manifest the complementary forces of structure and instinct through layers of abstract glyphs. Each mark and gesture builds toward what could be read as symbols, forms, and patterns. But the energy and movement in the work comes to the forefront. A reading of her gestural marks ultimately calls for an emotional translation, one that leads to a feeling of dynamic force and balance.

Melissa Meyer - Regale, 2005, Oil on canvas, © Melissa Meyer

Melissa Meyer - Regale, 2005, Oil on canvas, © Melissa Meyer

Margaret Neill

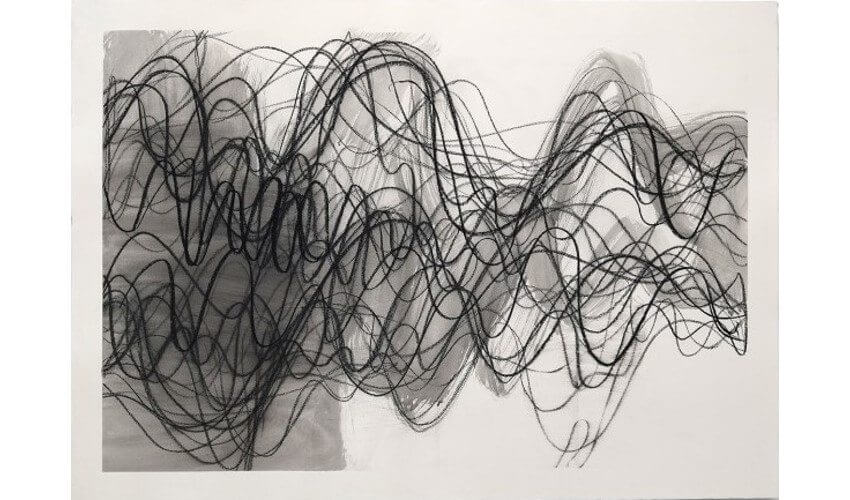

The elements of curve and line, which form the basis of all calligraphic art, also form the basis of the work of American artist Margaret Neill. Her paintings isolate the most expressive element of the calligraphic mark, the lyrical gesture, and incorporate it in the creation of layered compositions of lines in space. The depth of her gestural compositions confounds objective readings, defying the nature of script but embracing the dynamic, energetic potential that embodies the essence of the ancient tradition of calligraphy.

Margaret Neill - Manifest 1, 2015, Charcoal and water on paper

Margaret Neill - Manifest 1, 2015, Charcoal and water on paper

Featured image: Melissa Meyer - Ambassade (detail), 2007, Watercolour on hot press paper, © Melissa Meyer

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio