Carlo Carrà and His Futuristic Abstractions

When he died in 1966 at age 85, the Italian artist Carlo Carrà was known as a master of figurative painting. He was a respected teacher and a prolific art writer who influenced generations of realist artists. But prior to earning that reputation, Carrà was devoted to his first love: abstraction. Along with his friend Giorgio de Chirico, he co-founded Metaphysical Painting, an aesthetic precursor to Surrealism. And he was a co-writer and co-signer of the manifesto of the Italian Futurists. Despite only pursuing abstraction for a short time, Carrà painted some of Italy’s most important abstract masterpieces and helped develop many of the ideas by which future abstract artists would be inspired.

The Young Carlo Carrà

You could say Carlo Carrà began his career as a professional artist as a child. He was trained as an interior decorator at age 12, and by age 18 he was traveling Europe painting murals. His work exposed him to the Paris art scene at the turn of the 20th Century as well as to the political ideas circulating throughout Europe at that time. He was both a worker and an artist at a time when both classes were on the verge of revolution. While working in London, he was influenced by the ideas of exiled Italian anarchists, inspiring him to quit his job and return to Italy to study to become a fine artist.

In art school he was exposed to Divisionism, a technique that placed colors next to each other on a canvas rather than mixing them beforehand, as a way of tricking the eye into completing the picture. The concept of Divisionism was a profound departure from the realistic painting techniques that had preceded it, and it opened Carrà’s mind to the possibilities of abstraction. After finishing school in 1908, Carrà made the acquaintance of Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, three Italian artists who, like Carrà, were eager to express the modern, industrial aesthetic. Together these four wrote the Futurist Manifesto, which introduced the world to their love of speed, chaos and the violence of the mechanical age.

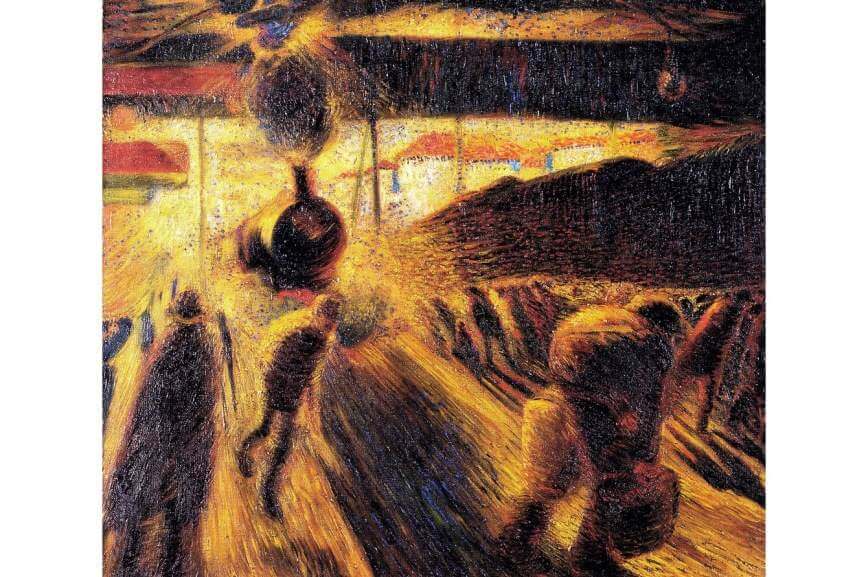

Carlo Carrà - La stazione di Milano (The station in Milan), 1910-11, 50.5 × 54.5cm, © Carlo Carrà

Being and Substance

One of the essential goals of Futurist painting was to convey movement and energy on the canvas; an effect they called Dynamism. Rather than stopping time to capture a subject in an exact, figurative way, the Futurists wanted to capture the sense of time marching on. They were enamored by the throngs of people living in modern cities surrounded by machines, noise and chaos. They wanted to convey that substance in their paintings. They wanted to paint what they felt.

One of Carrà’s first attempts at Dynamism was Stazione A Milano, painted in 1910. In this work he expresses the hive of activity surrounding a train station as a train is rolling in. Though somewhat representational, the painting reduces the human figures to ambiguous forms. The dominant elements in the image are light, smoke and the oncoming machine. The feeling is one of humanity passing into shadow as glorious industry barges forward in a cloud of ferocious fire and smoke.

Carlo Carrà - Jolts of a Cab, 1911, Oil on canvas, 52.3 x 67.1 cm, © 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Motion and Feeling

The most powerful visual element in Stazione A Milano was the yellow light, depicted as sharply angled yellow lines. The use of sharply angled lines became fundamental to Dynamism, as a way to convey speed, movement and power. Said Carrà in 1913, “The acute angle is passionate and dynamic, expressing will and a penetrating force.” His angles in his painting Funeral of the Anarchist Galli are even more severe, placing the utmost importance not on the subject but on conveying the chaos and energy of the scene.

Although in Funeral of the Anarchist Galli Carrà still relied somewhat on figuration, his goal was complete freedom from realisms. The operative word in this painting wasn’t funeral, it was anarchist. The point of it wasn’t to show a funeral, or to convey an image of any specific event; it was to convey the ideas of chaos and energy. Through an evolution toward total abstraction, Carrà felt he could attain a pure display of Dynamism.

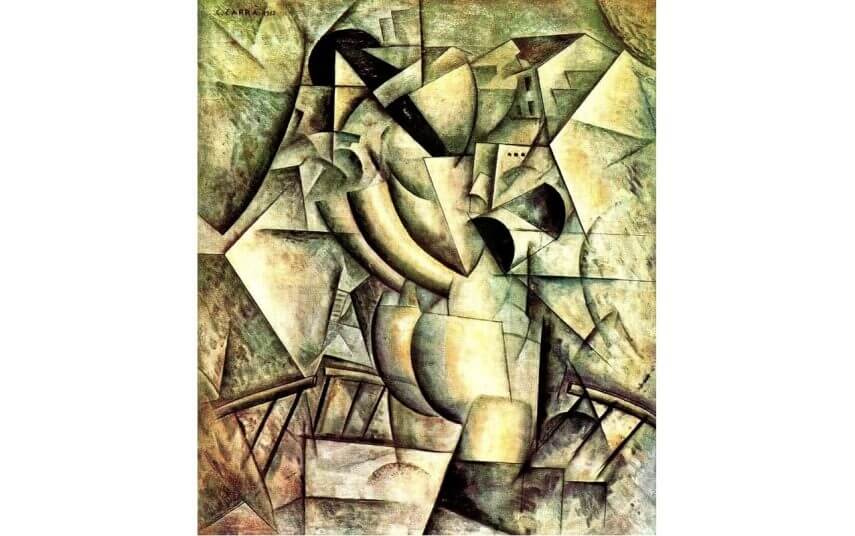

Carlo Carrà - Woman on a Balcony, 1912, Private Collection, © 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Cooperation of All the Senses

In order to increase the participation of all of a viewer’s senses, Carrà turned to the use of color. Prior to the Modernist revolution, color was used solely as a decorative element, not as the subject itself. Carrà and his contemporaries wanted to free themselves from the burden of using color in such a way. They wanted to explore color’s use as a subjective element, one that on its own could be the communicative element of a painting.

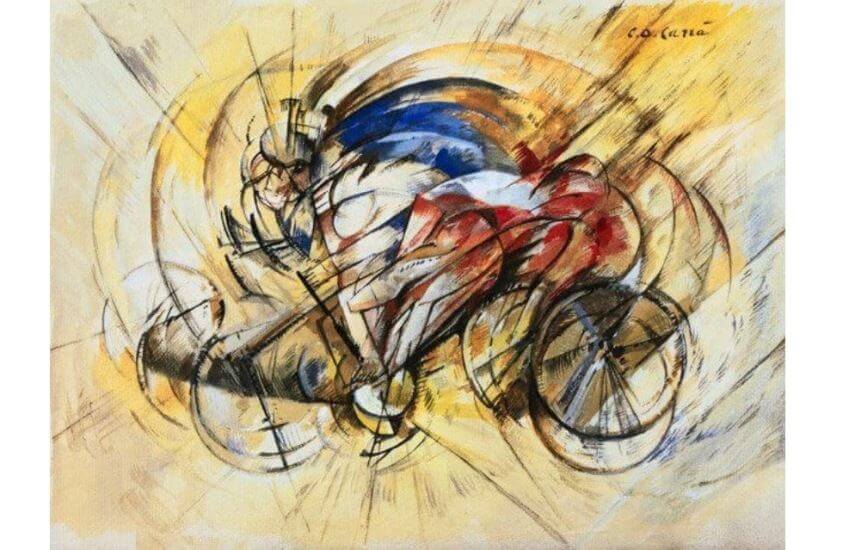

Carlo Carrà - Il Ciclista, 1913,© 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Carrà accomplished the free expression color’s subjective, dynamic qualities in Jolts of a Cab, painted in 1911. In it, he eliminated almost all figuration except for the faint realization of wheels repeating across the bottom of the canvas. The image explodes with bursts of color, a mix of abstracted forms and a cacophony of acute, angled lines. The result is a feast for the mind, a colorful, chaotic emanation of energy.

Carlo Carrà - Loneliness, 1917, © 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Static Energy

While the Futurists were focused on Dynamism, the Cubists were also attempting to convey an enhanced sort of realism, one that involved multiple perspectives of a single subject. Carrà felt Cubist paintings lacked vitality. He thought Cubism stopped the world and painted it, whereas he wanted the world to continue moving while he captured the feeling of that movement on the canvas. Referring to the Futurists efforts, Carrà said, “We insist that our concept of perspective is the total antitheses of all static perspective. It is dynamic and chaotic in application, producing in the mind of the observer a veritable mass of plastic emotions.”

Nonetheless, Carrà borrowed Cubist forms in his paintings, appropriating them to convey Dynamism. His painting Woman on a Balcony, painted in 1912, seems Cubist, but it doesn’t show multiple perspectives. Rather it uses Cubist shapes to show motion. A similar idea is evident in Carrà’s painting The Cyclist, from 1913, which combines abstracted Cubist forms with repetition to convey the sense of a bicycle racer in motion.

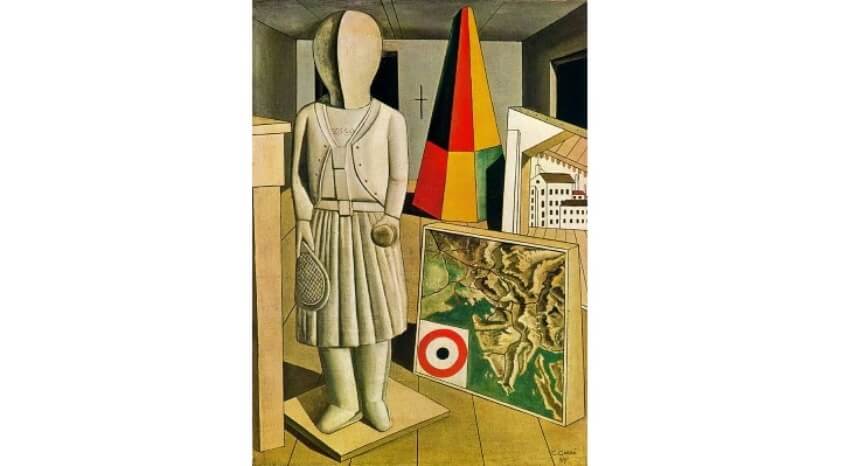

Carlo Carrà - The Metaphysical Muse, 1917, Oil on canvas, 90 x 66 cm, © 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

Metaphysical Painting

After World War I, Carrà abandoned Futurism and founded what he called Metaphysical Painting. Though not as obviously abstract as his Futurist works, Metaphysical Painting was the conceptual forerunner of several abstract movements that came after it. Through this innovative style, Carrà was attempting to paint the unseen. He was trying to arrive at the idea of something rather than painting the thing itself.

The dreamlike imagery in Carrà’s Metaphysical Paintings directly influenced the aesthetic of the 1920s Surrealists. And perhaps more significantly, these paintings depended on a symbolic language of forms to communicate abstraction. In The Metaphysical Muse, painted in 1917, the target isn’t a target; it’s an abstract symbol, an idea Jasper Johns would explore decades later. More than Futurism, maybe this was Carrà’s greatest legacy; the suggestion that abstraction can be achieved through symbolic or conceptual means, putting objects in contexts that challenge their meaning in an effort to create something new.

Featured Image: Carlo Carrà - Funeral of the Anarchist Galli, 1910-11, Oil on canvas, 198.7 x 259.1 cm, © 2017 Carlo Carrà / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio