Centre Pompidou Takes a Fresh Look at Cubism in a Comprehensive New Show

On 17 October, the first major Cubist exhibition in Paris in 65 years opens at The Centre Pompidou. Cubism (1907-1917) brings together more than 300 works in an attempt to expand our understanding of one of the most influential art movements of the 20th century. Most Cubist exhibitions focus on the founders of the movement: Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. This exhibition also spotlights their work, yet it goes far beyond that limited scope. It begins by examining rarely exhibited works by Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin along with examples of traditional African art that influenced Picasso. It then explores the galaxy of artists surrounding Picasso and Braque, who took their discoveries and expanded them into multiple other distinct positions. Not only are paintings included, but some of the most famous examples of Cubist sculpture are also on view, such as the cardboard guitar assemblage Picasso created in 1914. Finally, we see the legacy of Cubism through the works of artists like Amedeo Modigliani, Constantin Brancusi, and Piet Mondrian. According to its curators, the goal of this ambitious exhibition is to simply offer audiences a broader overview of the history of this important movement. But what they have actually accomplished goes a bit deeper. They have assembled a hopeful exhibition, one that encourages us to embrace the ideas of our contemporaries, and unabashedly build on the genius of the past.

A Change in Perspective

Many different explanations of Cubism exist. Some describe it as a geometric way of painting the world. Others call it a way of introducing the fourth dimension into art by showing movement. Others say it was an abstract a reduction of the shapes and forms found in everyday life. The best explanation I have ever heard is that Cubism was an attempt to re-examine perspective. Since the Renaissance, Western art was guided by specific rules when it came to visual art—rules about realism, acceptable content, and perspective. Paintings were expected to imitate life by embracing depth, perspective, and other illusionistic tools. Throughout the 1800s, however, those rules were challenged. The Impressionists challenged the rules about subject matter, making works that were solely about light. The Divisionists used experimental brush marks to raise questions about whether color exists in real life or is only interpreted in the brain. The Post Impressionists embraced mysticism, symbolism and spirituality, and proved formal elements like color and space could in themselves be worth pursuing as content.

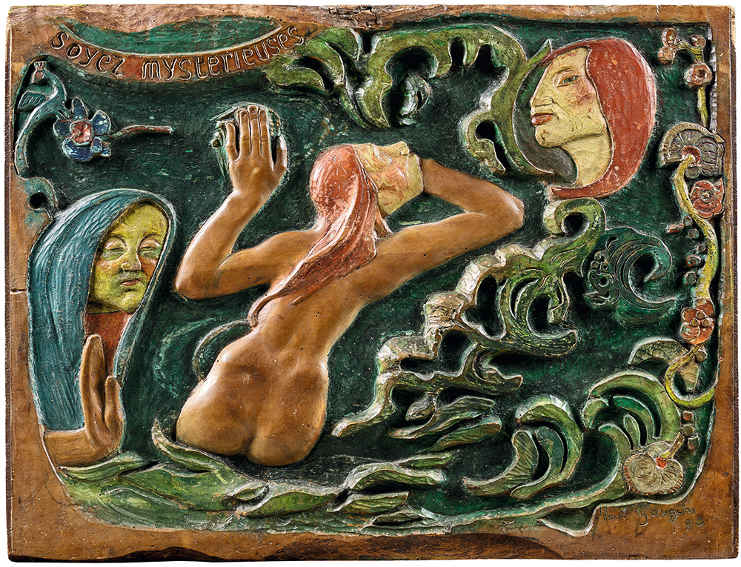

Paul Gauguin - Soyez mystérieuses, 1890. Bas-relief en bois de tilleul polychromé, 73 x 95 x 5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Tony Querrec

Cubism added to this mix the idea that reality is perceived far differently by the human eye than how it is usually portrayed in art. When we see something, we do not see it flattened out and perfectly still. The world is always moving, and we are always moving through it. We see bits and pieces of it from different angles. Light is changing constantly. The world is broken up into bits and pieces—some of which are invisible, yet we know they are there. Cubism attempts to show the fragments of reality reassembled into a single composition. It analyzes the world from multiple simultaneous perspectives, deconstructing life to show its complexity. Cubism (1907-1917) demonstrates how, in this respect at least, Cézanne was far ahead of Picasso and Braque. One of the earliest pieces in the show is the Cézanne painting “La Table de cuisine” (1890). From the table in the foreground to the baskets and chairs and dishes, every item in the picture is shown from a subtly different point of view. Simultaneity of perspectives is achieved in this work, declaring it as distinctly proto-Cubist 18 years before Picasso and Braque arrived at the same idea.

Paul Cézanne - La Table de cuisine. (Nature morte au panier), vers 1888-1890. Huile sur toile, 65 x 81,5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

The Art of Borrowing

One of the most refreshing aspects of Cubism (1907-1917) is that it does not shy away from the fact that these artists borrowed freely from each other. We sometimes put such a premium on originality, demanding that artists wildly innovate. This exhibition demonstrates that sometimes innovation simply means taking a tiny step forward building off of the accomplishments of others. We see “Masque krou,” from Côte d’Ivoire, one of the African masks that directly inspired Picasso. The face is divided into quadrants; the eyes are off balance; the features are divided up into geometric areas of shadow and light. Two nearby paintings by Picasso—“Portrait de Gertrude Stein” (1905-1906) and his self portrait from 1907—show how precisely Picasso imitated the visual language of the African mask. Yet then we see how he dissected these formal aspects and took the next step, using the ideas to deconstruct objects in space in paintings like “Pains et compotier aux fruits sur une table” (1908-1909), and to reveal the unseen aspects of character in works like “Portrait d’Ambroise Vollard” (1910).

Pablo Picasso - Portrait de Gertrude Stein, 1905-1906. Huile sur toile, 100 x 81,3 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA. © Succession Picasso 2018

As the exhibition goes on, we see how Sonia Delaunay thus borrowed the geometric language of Picasso—not to explore the physical world abut to use the shapes to explore the metaphysical potential of color relationships. We see how Piet Mondrian also borrowed the geometric aspects of Cubism, but unlike Picasso who complicated reality, Mondrian used geometry to simplify the world into its most basic elements. We see how artists like Juan Gris borrowed from Cubism to create a more graphic artistic style, which would go on to inspire poster artists. And we see how the collages of Synthetic Cubism inspired Dadaists like Francis Picabia. We also see so-called “Tubist” works by Fernand Léger, illustrating a nuanced alteration of the Cubist style that became a forerunner of Pop Art. Beautifully, there is no shame in this progression of influences. Quite the opposite. The thoughtful curation reminds us of the sheer joy of building off of the ideas of others. No one would say that any of these artists lacked in imagination. On the contrary, Cubism (1907-1917) proves that sometimes imagination is even more fruitful when it asks for help.

Featured image: Pablo Picasso - Guitare, Paris, janvier-février 1914. Plaque de métal et fer, 77,5 x 35 x 19,3 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. © Succession Picasso 2018

By Phillip Barcio