How CIA Funded Abstract Art Became a Cold War Weapon

I first heard about the existence of CIA funded art about a decade ago, when I came across an old article in the Independent referencing a British television series that aired in 1995-96 called Hidden Hands: A Different History of Modernism. The four-part series, which can be found in pieces today online, contradicts the narrative that Modernism, and in particular abstract art, developed through earnest aesthetic research and stolid intellectualism. It includes stories of persnickety, cleanliness-obsessed Bauhaus artists, French artists who either did or did not collude with Nazi occupiers, and the influence of the paranormal on early abstract artists. And the series also elucidates the secret, CIA-funded program to promote American culture internationally between the years of 1950 and 1967. Under the auspices of various fake foundations and something called the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), the CIA funded newspapers, publishing companies and traveling art exhibitions for decades after World War IIin an attempt to undermine communism by promoting America as a place of freedom and tolerance toward new ideas. The program died in 1967 after the Saturday Evening Post exposed its activities, drawing universal ire from liberals, conservatives, artists, art lovers, and art haters alike. But regardless of public opinion, the secret plan to promote American culture internationally worked. Whether or not the Russians believed it, and whether or not it was true before their campaign started, the CIAcreated the reality they described. They helped make America a place of creative freedom where artists and intellectuals could be wildly innovative and also financially successful. Oddly, in fact, thatparadigm may have even been more real in 1967 than it is today.

How the CIA Funded Abstract Art

The marriage of the CIA and abstract art might seem bizarre. The image of straight-laced federal agents feels antithetical to that of starving, cigarette-smoking, hard-drinking, bohemian artists. But one fact this story demonstrates clearly is that appearances are not everything. When the CIA was founded in 1947, it had one goal: to defeat communism. The main communist power in the world at that time was the Soviet Union, and their official artistic style was Socialist Realism, which demanded realistic artworks praising communist values, such as sculptures of muscular, proud farmers or paintings of humble, dedicated soldiers. But the democratic world has no official art style. Artists there pursue any style or subject matter they want. So in that context, of course any self-respecting, freedom-loving CIA agent should embrace abstract art. It is quintessentially American. Not only does it not extol one particular viewpoint, it embraces the possible validity of multiple simultaneous viewpoints.

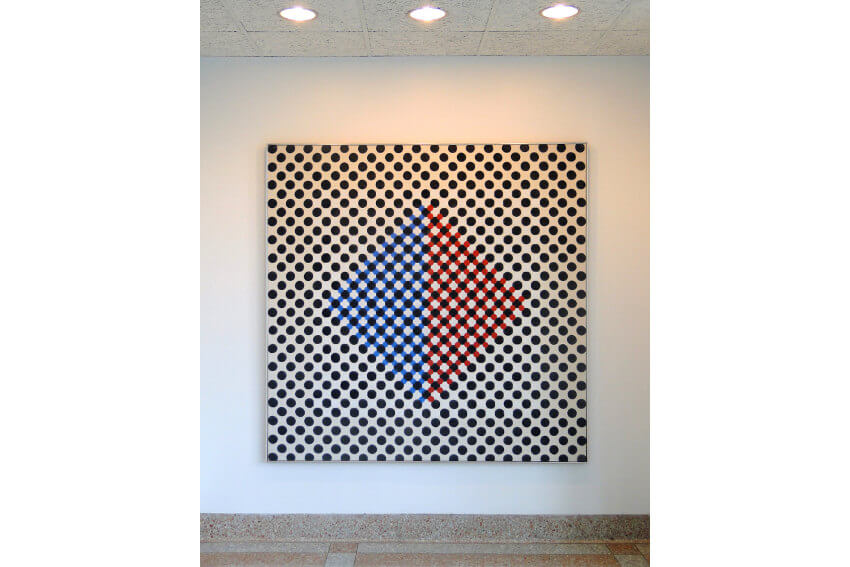

Robert Newmann - Arrows, 1968, © Robert Newmann

Robert Newmann - Arrows, 1968, © Robert Newmann

Back in the early 1950s, as CIA efforts to promote America as an artistic promised land were really getting off the ground, the dominant emerging art style in the US was Abstract Expressionism. Its unfettered, experimental brushstrokes and nonrepresentational imagery seemed to CIA agents to loudly proclaim the principals of American liberty. That is how it came to pass that artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning became unwitting tools of anti-communist propaganda efforts. Over the course of several years, the agency helped fund at least three major European traveling exhibitions of Abstract Expressionist art. The most infamous case occurred when the Tate Gallery lacked the necessary capital to host the 1958 exhibition The New American Painting following its appearance in Paris. An American philanthropical charity called the Farfield Foundation, run by American business magnate Julius Fleischmann, donated the funds. That foundation was entirely funded by the CIA.

Thomas Downing - Center Grid, ca. 1960, © Thomas Downing

Thomas Downing - Center Grid, ca. 1960, © Thomas Downing

A Colorful Legacy

As it turned out, following the expose in the Saturday Evening Post, the multitude of pro-American cultural operations funded by the CIA either dissolved or went into private hands. But that did not end the connection between the CIA and abstract art. In 1968, the infamous art collector Vincent Melzac, an avid patriot and supporter of painters associated with the Washington Color School, loaned 11 abstract paintings to the CIA to hang at its headquarters. They hung there in a hallway until 1988, when the CIA purchased the paintings. And they still hang in that hallway today. Their presence in that environment may seem odd, but they serve many active roles. In a decorative sense, they are a welcome burst of color in an otherwise sterile environment. And in a national security sense, they are an invaluable tool. How is that? According to an article by Carey Dunne in Hyperallergic in 2016, the agency routinely sends agents to look at its abstract art collection in hopes their visual analyses of the paintings will lead to breakthroughs in their anti-terrorism efforts.

Gene Davis - Black Rhythm, 1964, © Gene Davis

Gene Davis - Black Rhythm, 1964, © Gene Davis

Yes, that is correct. The CIA uses abstract art to challenge the perceptions of their agents. For some reason, knowing that makes me happy. I also understand why some people find the idea of CIA involvement in the arts distasteful. And it is equally understandable why the press exposed those secret activities back in the day. But I also appreciate the notion that an official government agency makes it a matter of standard operating procedure to contemplate art, and to value America as a place where artists are free to make whatever work they want. I do not know whether the CIA inadvertently made Abstract Expressionism the big deal it eventually became. Nor do I know how many museums, galleries, art collectors or art dealers remain under the direct influence of people with a political or social agenda. All I know is if forces behind the scenes are working to promote the ideas of freedom, liberty and experimentation by funneling money into the creation and promotion of abstract art, I am okay with that. And if they are looking for any not-so-secret agents, I might even be available.

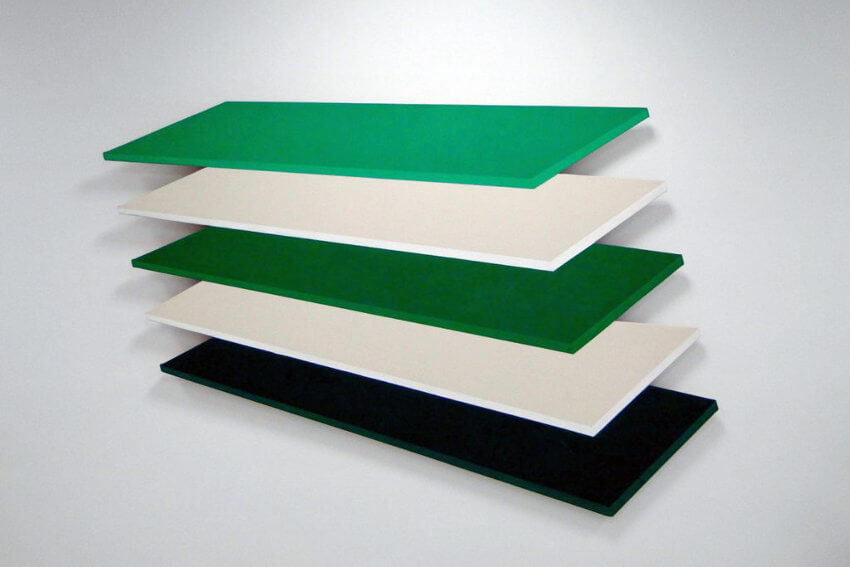

Thomas Downing - Planks, 1967, © Thomas Downing

Thomas Downing - Planks, 1967, © Thomas Downing

Featured image: Thomas Downing - Center Grid (detail), ca. 1960, © Thomas Downing

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio