Abstract Wonders of Cuban Art on View in Miami

Oct 11, 2017

What defines Cuban art has long been the subject of debate. The main question: does the term Cuban art refer to art made by Cubans still living on the island, or does it refer to art made by artists in the Cuban diaspora? Or should it refer to both? For more than two generations, Cuban artists living on the island have been completely regulated by the government. No artist can exhibit or publish their work publicly there unless it adheres to the strict guidelines of the dictatorial regime. This being the case, it is difficult to imagine that art made by Cubans on the island comes from a place of pure inspiration or creative integrity. It is always under the influence of political forces, and therefore an argument can be made that it can be perceived of as propaganda. But although art made by artists living in the Cuban diaspora might be more free, it is not purely Cuban. Artists of Cuban heritage living in the United States or elsewhere are multi-cultural by definition. They can speak to one aspect of the Cuban experience, but they cannot speak to the experience of still being on the island, forced by the government to adhere to a particular style or subject matter. It would seem as though perhaps both sides of this debate could come together. Like, perhaps by examining the work of Cuban artists living on the island alongside that of artists in the diaspora, a more complete notion of what defines Cuban art could be assembled. But that is a more controversial suggestion than one might think. Just ask the curators of Between the Real and the Imagined: Abstract Art from Cintas Fellows. This unassuming sounding exhibition, which closes on 22 October 2017, has created an international controversy that threatens the reputation of a new museum and challenges the status of the most important source of monetary support for Cuban art.

Meet the Cintas Foundation

Oscar B. Cintas was a Cuban industrialist. He was born in 1887 in Sagua la Grande, a coastal city in central Cuba. When Cintas was a child, the city of his birth was undergoing a massive transformation from a relatively new municipality into an important commercial and industrial capital. Cintas would have the opportunity to grow along with the local economy. After attending university overseas, in London, England, he returned to the island of Cuba and became a magnate in the sugar and railroad industries. Because of his business connections, Cintas was selected to serve as the Cuban ambassador to the United States during one of the most difficult and tumultuous times in Cuban political history: 1932 through 1934. This was a time of upheaval and revolution, when a loose, provisional government took over, and for the first time in the modern history of Cuba instituted reforms that were not controlled by either Spain or the United States. That period ended in 1934 when a US backed military coup overthrew the administration.

Cintas, like many of the other Cuban industrialists of his generation, thrived financially throughout the strife. One of his favorite interests outside of business and politics was the acquisition of objects of art. Having been educated overseas, he had a global sense of aesthetic taste. He collected masterpieces from all over the world, including rare manuscripts, like the only known first edition of Don Quixote, and one of only five known original copies of the Gettysburg Address, the most famous speech by Abraham Lincoln, delivered at a pivotal moment in the American civil war. And his interest in art went beyond collecting. Cintas also wished to use his massive fortune to assist artists in the creation of their work. To that end, he made plans to start a foundation that would give grants to artists of Cuban descent. He died in 1957, before his foundation could be set up. But following his wishes, the executors of his estate did eventually set up the Cintas Foundation. Since 1959, the foundation has been the most important financial supporter of artists from all over the Cuban Diaspora.

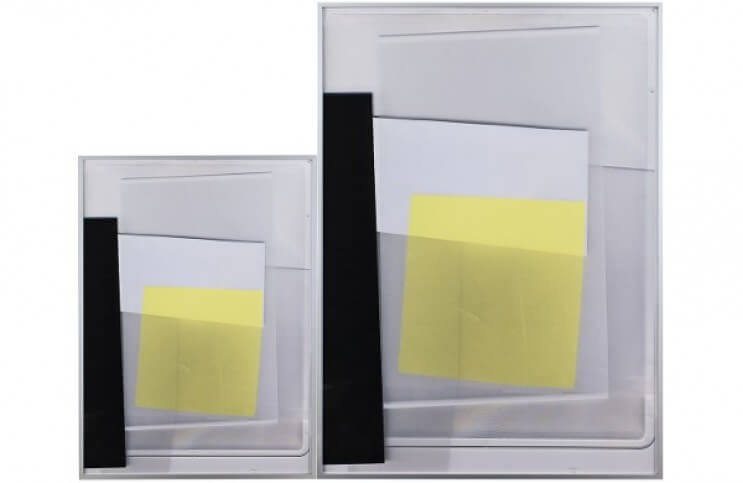

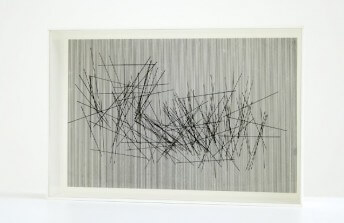

Zilia Sanchez - Untitled, Mixed media on canvas, 31 x 23 in

Zilia Sanchez - Untitled, Mixed media on canvas, 31 x 23 in

Controversy and the Cintas Collection

Every year, the Cintas Foundation awards fellowships to Cuban diaspora artists in the realms of visual art, literature, music, film and architecture. One of the arrangements the Foundation makes with its Fellows is that in return for the financial support, they contribute a work of art to the Cintas art collection. Over the decades, the Cintas Collection has grown to become the most important and diverse collection of Cuban diaspora art in the world. The Foundation oversees this collection, and periodically allows exhibitions to be curated from the work within the collection. But it is a difficult task sometimes to put together a cohesive exhibition, because there is no strict principle that guides the choices of the jurors when awarding a new fellowship. The work spans every conceivable aesthetic range. But that is the point. It does not represent a single point of view. It represents the multiplicity of what it means for something to be considered Cuban art.

Nonetheless, this year the Foundation saw fit, as it sometimes also has in the past, to assemble works from the collection according to a particular theme. The theme they chose in this case was Cuban abstraction. For an exhibition space, the Foundation chose what at the time seemed like the perfect fit: the brand new American Museum for the Cuban Diaspora in Miami, Florida. But then a controversy erupted. The Foundation released a memo on its website that indicated that starting this year, for the first time ever, artists currently living on the island would also be considered for Cintas Fellowships. Previously, only artists from the diaspora were considered. This enraged the decision makers within the American Museum for the Cuban Diaspora, because their mission is explicitly to support art and artists from the diaspora only. They canceled the exhibition. But their decision was not universally beloved. Both points of view are valid, it would seem. To support artists living on the island means tacit support for the dictatorship that controls their artistic output, because In Cuba, art is always political. And yet in the opinion of the Cintas Foundation, the entire Cuban art story can simply not be told without also including art made under the dictatorship, including the work of artists currently living on the island.

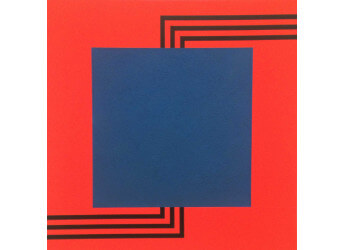

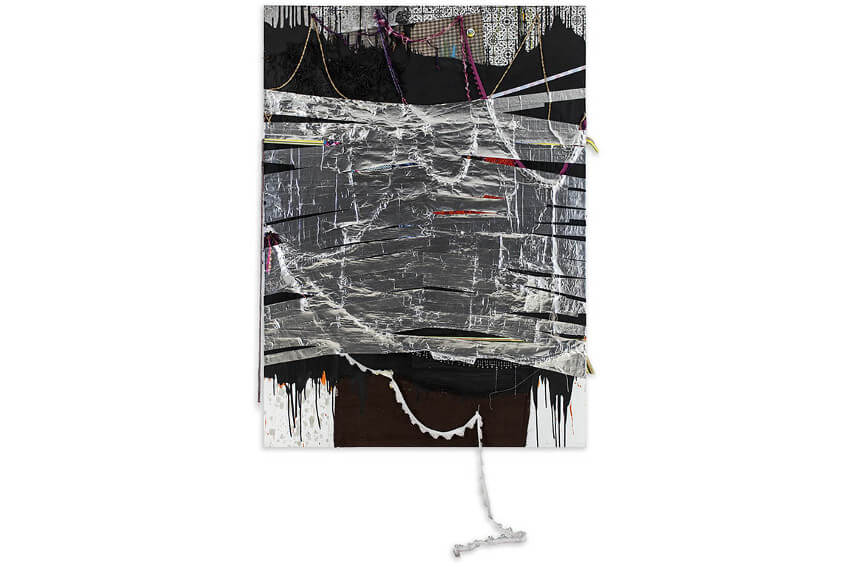

Gean Moreno - Untitled, 2006, Mixed media Mixed media on canvas, 86 x 63 in

Gean Moreno - Untitled, 2006, Mixed media Mixed media on canvas, 86 x 63 in

Between the Real and the Imagined

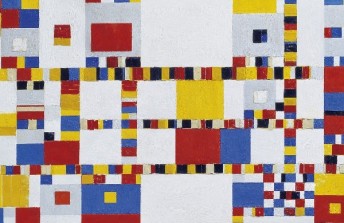

After the American Museum for the Cuban Diaspora canceled the Cintas Foundation exhibition, curators simply found a new venue—the Coral Gables Museum, in Coral Gables, Florida, just outside of the city of Miami. The space is smaller, so the exhibition had to be pared down. But that also led to a much tighter, well-edited selection of work. The general scope of Between the Real and the Imagined has to do with geometry, structure and line. It includes works from artists that represent the entire history of the Cintas Fellowship. Among them is Carmen Herrera, perhaps the most famous Cuban-born artist at this moment. Herrera, aged 102, just had a major retrospective at the Whitney in New York. She was a Cintas Fellow from 1969 to 1972. Also on view in the show is work by Cuban abstract art pioneer Rafael Soriano, the recipient of a Cintas Lifetime Achievement Award in 2014, and new work from contemporary abstract sculptor Leyden Rodriguez Casanova. Born in Havana in 1973 and currently residing in Miami, Casanova was a Cintas Fellow in 2011.

For the casual art viewer who can look beyond the politics, Between the Real and the Imagined offers an excellent glimpse of an underexposed aspect of Cuban diaspora art. Perhaps because of the intense political nature of recent Cuban history, most exposure seems to go art that reflects in figurative ways on issues related to Cuban exile or the complexities and tragedies of the revolution. This exhibition highlights a different aspect of the Cuban experience, and will undoubtedly lead to a greater appreciation of the depth and breadth of Cuban heritage. But there is also perhaps a hidden message in the title of this exhibition. What is real and what is imagined, after all? These geometric forms are real, are they not? Is it only their meaning that is imagined? And is it real that artists living on the island are truly under the control of the government. Has their ingenuity never led them to discover ways to be free, at least in the studio? Is the power of a brutal government only imaginary? Or is mind control real? Is there truly any separation between those living in exile and those living on the island? Is heritage real or imaginary? This exhibition is small, but it is important. It raises the questions art so often raises, such as what is concrete; what is abstract; and how can we know the difference between what we imagine, what we believe, and what we know to be real.

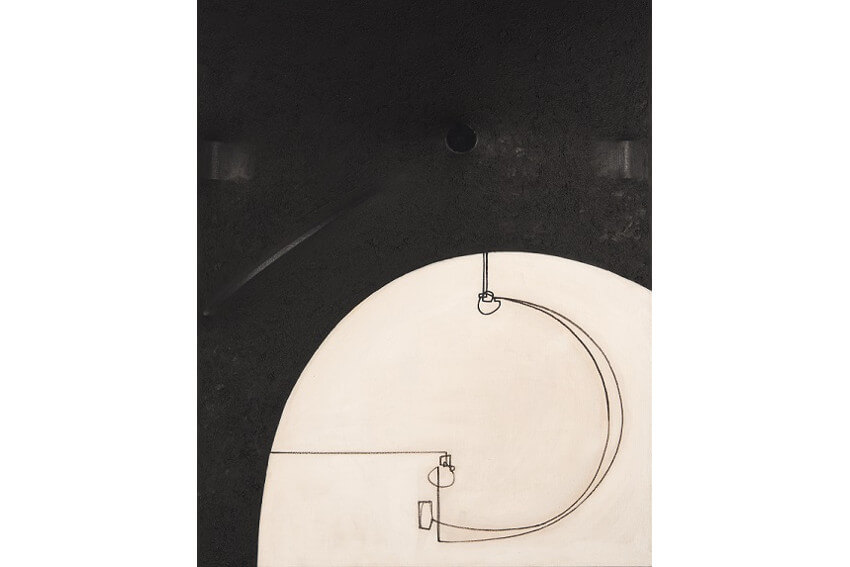

Featured image: Angela Valella - Untitled, 2006-2007, inkjet print on silver metallic paper

All images © Cintas Foundation, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio