How Latin American Artists Altered Our Perceptions of Modern Art

Jul 14, 2017

A new book by Alexander Alberro, a Professor of Art History and the Department Chair at Barnard College, offers insights into the global development of abstract art in the 20th Century. Titled Abstraction in Reverse: The Reconfigured Spectator in Mid-Twentieth-Century Latin American Art, the book examines how Latin American artists consumed and then responded to European Modernism beginning in the 1940s. In particular, Alberro looks at the work of important Latin American artists such as Jesús Rafael Soto, Julio Le Parc and Tomás Maldonado in context with how those artist were influenced by the philosophies of the European art movement known as Concrete Art. The essence of Concrete Art is that aesthetic phenomena should come directly from the mind of the artist and not be based on the natural world. Concrete Art calls for the use of pure, universal elements such as planes, shapes, forms, lines and colors, and the elimination of sentimentality, drama, narrative and symbolism. Basically, Concrete Art references only itself. The philosophies of Concretism were appealingto mid-20th Century Latin American artists who were seeking ways to respond to their rapidly globalizing culture. Concrete Art offered a strategy for connecting all people regardless of nationality, race, gender, or other artificial differentiations. But as Alberro explains in his book, the Latin American artists of the mid-20th Century did not simply copy the work of European Concrete artists. They took the basic ideas of Concrete Art and turned them into something far more complex. As they evolved into what Alberro calls post-Concrete artists, these artist developed an aesthetic outlook that profoundly changed the way art is defined, and continues to affect how we understand the role art plays in our daily lives today.

Productive Misunderstandings

We take it for granted today how simply we can access images from all over the world via the Internet, and how easy it is to acquire detailed descriptions and interpretations of the work of artists, wherever they happen to live. But as Alberro points out, in 1940s Latin America artists had quite an awkward time accessing information about the art being made in other places. Alberro explains that when trying to study European Modernism, all Latin American artists really had were black and white copies of images of artworks. This partial access led to what he calls “productive misreadings.” For example, Alberro mentions an anecdote about the artist Jesus Rafael Soto, saying,“When Soto finally saw a Mondrian, he realized he had it all wrong.”

Color is a vital element of the work of Piet Mondrian, but in a black and white image that essential element is obviously lost. And the poor quality reproductions Soto was able to see also made the surface texture of European Modernist paintings appear to be completely smooth. But while these misunderstandings stopped Soto and other Latin American artists from grasping the true aesthetic intents of artists like Mondrian, it also led them to develop their own interpretation of the potentialities revealed in their work. They interpreted a limited palette and smooth surfaces as statements of true modernity, purified through simplification. And despite their misunderstandings, they grasped the most essential element of Concrete Art: that an artwork possesses its own logic that can be grasped without having to relate it to any a priori interpretations of meaning.

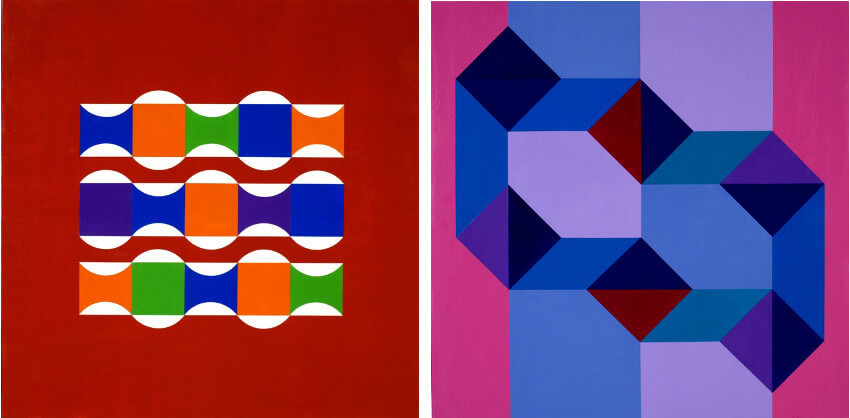

Tomas Maldonado - Anti-Corpi Cilindrici, 2006 (left) and Untitled (right), © Tomas Maldonado

Tomas Maldonado - Anti-Corpi Cilindrici, 2006 (left) and Untitled (right), © Tomas Maldonado

Beyond Concretism

The idea of meaning was of paramount importance to Latin American post-Concrete artists. In the past, the most common way to conceptualize art was to think about artists creating something ahead of time in a studio and then exhibiting that art object later in a special place where viewers could contemplate it. The artist was a creator of an object, and that object was infused with meaning as it was made, and that meaning was inexorably linked with the place, time, and circumstances under which the artwork was created. The viewers therefore were secondary in importance to the artwork. Despite whatever personal interpretations they may feel inclined to offer when viewing the art, they were ultimately always forced to accept the interpretation put forward by the artist, or by official surrogates like critics, historians or academicians. And even Concrete Art, despite its modern approach, still embraced the idea of artists as object makers, and viewers as object contemplators.

But according to Alberro, the Latin American post-Concrete artists flipped this idea on its head. They rejected the idea that the meaning of an artwork was infused into the work prior to its exhibition. They imagined that perhaps the creation of an artwork is only the first step toward the experience of meaning that may eventually result from its existence. In describing this philosophical change, Alberro coins the term “aesthetic field.” He describes the aesthetic field as the circumstances under which an artwork and a spectator come together. The aesthetic field includes a physical space, such as a gallery or a public square; the conditions within that space, such as the lighting, the climate, or the ambient noise; the artwork, of course, as well as the spectator; and it also includes three-dimensional and four-dimensional reality, meaning it includes not only solid objects in space, but also the experiences and relationships that play out between those objects in time.

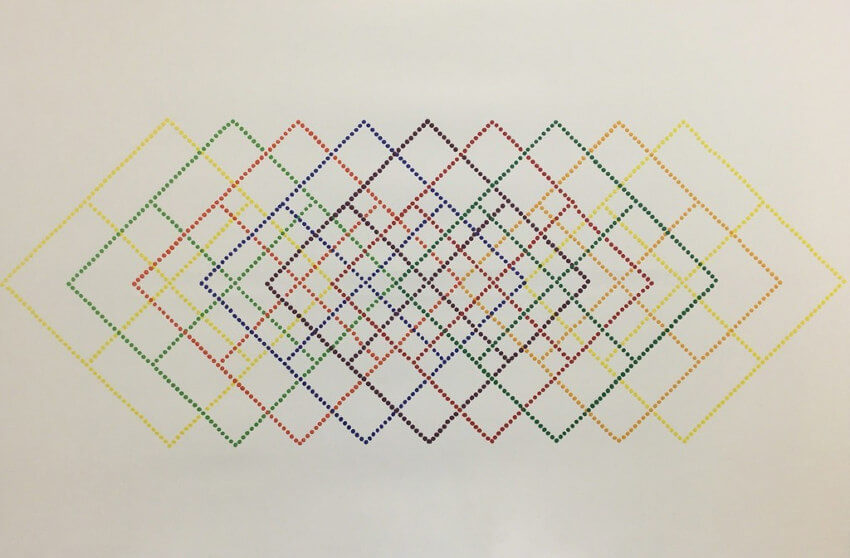

Julo Le Parc - Alchimia, 1997, Acrylic on paper, 22 4/5 × 31 1/2 in, 58 × 80 cm, photo credits Galeria Nara Roesler

Julo Le Parc - Alchimia, 1997, Acrylic on paper, 22 4/5 × 31 1/2 in, 58 × 80 cm, photo credits Galeria Nara Roesler

The Fabric of the World

In other words, Alberro argues that by placing the artwork as just one element of a dynamic experience that occurs within the aesthetic field, Latin American post-Concrete artists reintegrated art into human society. Rather than viewers contemplating the meaning of an artwork, they could now collaborate with the artwork to construct a meaning that is flexible and ephemeral. And rather than an artwork existing on its own as a predefined object, situations could be constructed in which an artwork is simply one element of the larger fabric of the unfolding reality. Of course, the artwork may still have its own defined aspects, such as a particular arrangements of shapes or colors, but those aspects could now have a shifting level of importance depending on how they are perceived by spectators within the aesthetic field.

That shifting system of relations between art objects and viewers meant that every work of post-Concrete art could be defined as a dynamic, kinetic element of a larger social experience, one that takes priority over the artwork itself. One of the key examples Alberro offers of an artist who demonstrated this evolution in thought is Jesus Rafael Soto. Anyone familiar with the Penetrables Soto created during the mature phase of his career will surely understand why. Soto constructed his Penetrables from a multitude of hanging plastic cords. By coloring parts of the cords, he could give the impression of a solid form hanging suspended in space. But rather than simply admiring and contemplating a Penetrable, viewers are encouraged to walk into the jungle of cords, putting the cords into motion and destroying the illusion of a solid object. Each viewer experiences a range of sensations beyond the visual, such as touch, smell, and hearing. The personal experience each viewer therefore has with a Penetrable leads that viewer toward a unique empirical judgment of the meaning of the work—a meaning that transcends the work and speaks to the larger experience of life that viewer is having.

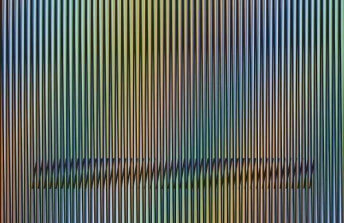

Jesus Rafael Soto - Courbes Immaterielles, 1982, Wood and aluminium, 98 2/5 × 196 9/10 in, 250 × 500 cm, photo credits La Patinoire Royale, Brussels

Jesus Rafael Soto - Courbes Immaterielles, 1982, Wood and aluminium, 98 2/5 × 196 9/10 in, 250 × 500 cm, photo credits La Patinoire Royale, Brussels

The Post-Concrete Legacy

In addition to illuminating an underestimated aspect of Modernist art history, Abstraction in Reverse also provides a better understanding of a contemporary debate about the function of art in society. That is to say, there really is no common agreement about what the function of art is, or whether it in fact has any unique function at all. Politicians argue that art education has no quantifiable benefits. Meanwhile, the art market thrives, and is simultaneously criticized for prioritizing the skyrocketing commercial value of art. Mainstream art criticism has devolved into little but a series of either denigrating commentaries or puffed up praises based on nothing but the personal tastes of art writers. Meanwhile, no one seems willing or able to articulate the universal value of aesthetic phenomena in the broader context of our time.

Perhaps art is not unique in its supposed function as a provider of meaning. After all, if the meaning and purpose of an artwork is determined by spectators within the aesthetic field, that means one artwork can be switched out with another artwork without the overall experience being compromised. For that matter, could the artwork be replaced by a football game, a fireworks display, or a political speech? Would the end result of spectators constructing meaning be the same? What this book insightfully suggests is that the Latin American post-Concrete artists glimpsed something we are only fully coming to understand nearly a century later: that art can assist in the construction of an aesthetic phenomenon, but it is most likely the common social experience of people coming together to share that aesthetic phenomenon that results in meaning being constructed, not the art itself.

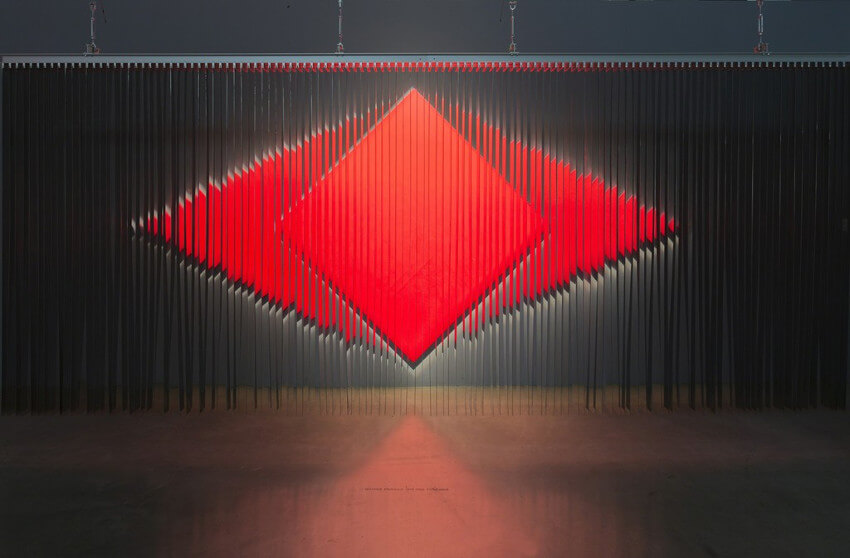

Julio Le Parc - Cloison à lames réfléchissantes, 1966-2005, Steel, wood, light, 90 3/5 × 103 9/10 × 31 1/2 in, 230 × 264 × 80 cm, photo credits Galeria Nara Roesler

Julio Le Parc - Cloison à lames réfléchissantes, 1966-2005, Steel, wood, light, 90 3/5 × 103 9/10 × 31 1/2 in, 230 × 264 × 80 cm, photo credits Galeria Nara Roesler

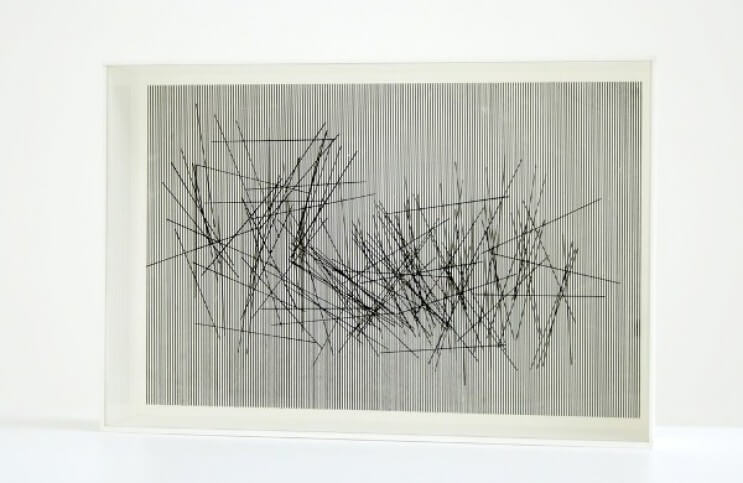

Featured image: Jesus Rafael Soto - Vibrations, 1967, Screen print on Plexiglass, acrylic, 11 3/5 × 16 1/2 × 3 1/10 in, 29.5 × 42 × 8 cm, photo credits Galerie Hans Mayer, Düsseldorf

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio