The Sibling in the Shadow - Diego Giacometti

Jul 5, 2017

This summer the Tate Modern has mounted an intensive retrospective of the work of Alberto Giacometti, one of the most important artists of the 20th Century. But many people attending the show may not realize that had it not been for another Giacometti - Diego Giacometti, the younger brother of Alberto—an exhibition such as this may never have been possible. Alberto died in 1966 at the age of 65, but his brother Diego lived nearly another two decades. In that time, Diego refined his own personal style and created a reputation for being an artist and a craftsman of unusually high skill. This came as a shock to many fans of his more famous brother, but to anyone who knew both Alberto and Diego well it was no surprise at all. The two brothers grew up together in a remote valley in the Swiss Alps then lived within blocks of each other in Paris for most of four decades. They shared a common studio space, and both spoke frequently and openly about their reliance on each other, and about how they collaborated on virtually every item either of them made. So as the Tate is now offering us this chance to take stock of the impressive oeuvre of Alberto, we should take time once again consider the legacy of Diego: the other Giacometti.

An Immense Weariness

In a 1985 article in the New York Times printed almost exactly one year before the death of Diego Giacometti, journalist Michael Brenson describes the impression he had when first meeting Diego 15 years prior. Brenson writes, “Diego has grown younger with age. When I met him in 1970 while doing research on Alberto's early work, he seemed old. He was always courteous and helpful, but in conversation, he could not concentrate long on any subject. It was not so much the amount he drank at dinner but the way the wine seemed to dredge up an immense weariness.” But what was the initial cause of such weariness? And what was it that made Diego seem later to grow younger with age? Benson goes on to describe Diego as an artist who had always felt subordinate to his studio mate and employer, who just happened to also be his brother. He had always humbled himself around Alberto, refusing to show his own work and always taking a back seat when it came to acknowledgment. But all of that changed as the years transpired after Alberto died. Diego got farther and farther away from the shadow of the reputation of his brother and began celebrating the full richness of his own talents.

Diego Giacometti - Pair of wall sconces, Gilded bronze, 12 in (30.5 cm), Photo credits DeLorenzo Gallery

Diego Giacometti - Pair of wall sconces, Gilded bronze, 12 in (30.5 cm), Photo credits DeLorenzo Gallery

Alpine Roots

It could be argued that without Alberto, Diego would not have even survived into old age. He may have become destitute, died of liver disease, been killed in war, or lived and died in anonymity in his hometown. Both boys were raised in the same place and circumstances, but each developed into very different young men. Their father was also an artist, and despite living in a remote village was connected with the Swiss intellectual and artistic elite. Alberto took advantage of this connection, developing an early affinity for philosophy, poetry, and the intellectual side of life. Diego meanwhile roamed the countryside, climbing every mountain, exploring every stream, and familiarizing himself with the innumerable life forms that inhabited the wilderness surrounding him.

One way to put it is that Alberto connected with the world through his mind while Diego connected with the world through his body. But both boys had heart, especially for each other. After Alberto moved to Paris in 1922 to devote himself to becoming an artist, it became clear that Diego was only interested in drinking, socializing and having fun with life. So in 1925, their mother sent Diego to Paris to live with Alberto, in an effort to save Diego from himself. Alberto put Diego up in an apartment and gave him work in his studio. Despite their different ways of understanding the world, the boys had something of value to offer each other. Alberto saved Diego from self-destruction, while Diego saved Alberto from having to rely on outside craftspeople. And it turned out Diego was masterful at grasping the craft of sculpting, casting, carving and bronzing, and he also had a natural artistic eye. He was the perfect studio partner for Alberto, who could hence focus on the big ideas of his art without having to do all of the handiwork himself, or trust it to strangers.

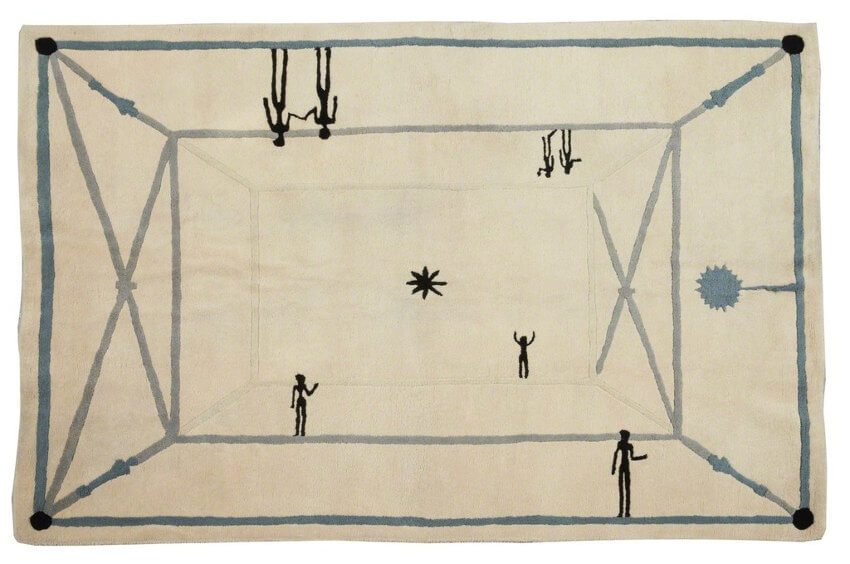

Diego Giacometti - The Encounter, 1984, 68 1/10 × 92 1/2 in (173 × 235 cm), Photo credits Galerie Marcilhac, Paris

Diego Giacometti - The Encounter, 1984, 68 1/10 × 92 1/2 in (173 × 235 cm), Photo credits Galerie Marcilhac, Paris

Another Set of Hands

When looking back over the impressive oeuvre that Alberto Giacometti left behind, it is essential to understand that almost all of it passed through the hands of his brother Diego. It was Diego who had the engineering talent to devise ways to build the supports for the heavy, yet delicate, thin sculptures for which Alberto became famous. It was also Diego who created and applied the patina to the bronze statues Alberto created. Diego made the molds, he carved the stone: basically he was another pair of hands for his famous brother. But he was also something far more important. He was another mind.

Those who lived in close proximity to the brothers in their Montparnasse neighborhood of Paris have recalled hearing the two engaged in nightly conversations about their work. There was not a single artwork Alberto made that did not first get discussed with Diego. It is impossible to calculate the value to an artist of a trusted conspirator. Somehow the experiences of these two men combined in ways that resulted in one of the most iconic aesthetic visions of humanity ever created. But without the salt-of-the-earth, sometimes brutish, basic, country boy perspective Diego embodied, it is possible Alberto never could have fully comprehended or adequately expressed the human experience as brilliantly as he did.

Diego Giacometti - Rare Bronze Sconces, Mid 20th Century, Bronze, 15 × 17 × 6 in (38.1 × 43.2 × 15.2 cm), Photo credits Galerie XX, Los Angeles

Diego Giacometti - Rare Bronze Sconces, Mid 20th Century, Bronze, 15 × 17 × 6 in (38.1 × 43.2 × 15.2 cm), Photo credits Galerie XX, Los Angeles

Developing His Own Style

Perhaps the weariness observed in Diego after Alberto died indeed came from the fact that he had worked so hard all of his life in the service of the career of someone else, and had done so, perhaps, at the expense of his own true character. But gradually after Alberto passed away Diego his own aesthetic vision, and expressed the immense talent he possessed as a craftsman and an artist. His style is much different than that of his brother in that it is more narrative, more straightforward, more humorous and whimsical. And in many ways it is also more approachable, thanks to its roots in the folk culture of everyday people.

But it is also comparable to that of his brother in that it strives for and achieves the highest standards of beauty, and declares itself as vital, important, and transcendent of time. What is particularly impressive is that Diego achieved such high standards while working in an often overlooked milieu of art: he made furniture. The delicate and complex pieces he created in the decades following the death of his brother have become part of the collections of some of the wealthiest and most famous names in Europe. His tables and lamps, which often bear masterful images of figures and scenes from mythology, come up periodically at auction and fetch upwards of half a million dollars or more.

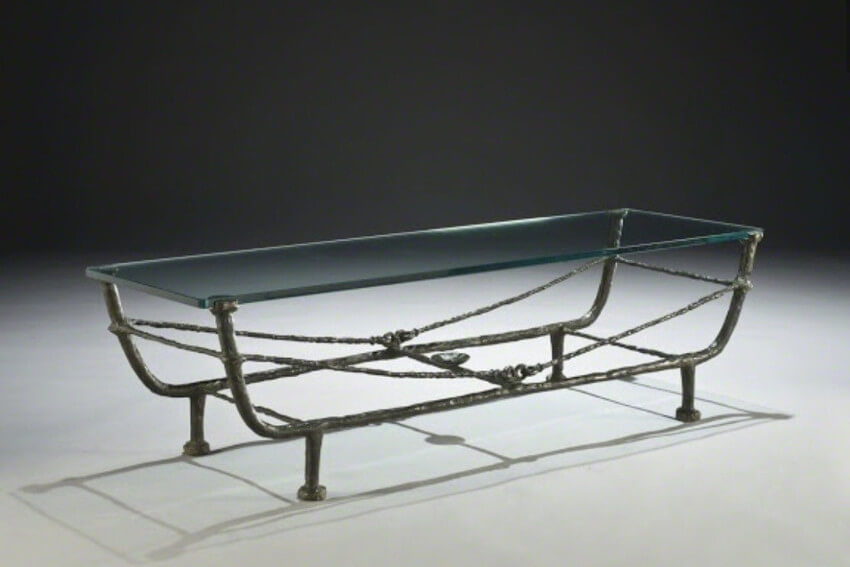

Diego Giacometti - Berceaucoffer table, ca. 1968, Bronze, 47 1/5 × 15 7/10 × 17 7/10 in (120 × 40 × 45 cm), Photo credits Jean-David Botella

Diego Giacometti - Berceaucoffer table, ca. 1968, Bronze, 47 1/5 × 15 7/10 × 17 7/10 in (120 × 40 × 45 cm), Photo credits Jean-David Botella

The Value of Relationships

Today the work of Diego Giacometti is included in the collections of many museums. More than 500 of his pieces are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris. But the presence of his work in some museums may be difficult to notice at first. One of the most high profile commissions Diego Giacometti ever received was from the Musee Picasso, which opened in Paris in 1985, the same year Diego died. Diego was commissioned to provide not art for the museum, but interior furnishings for the building itself. Particularly notable are his chandeliers. About them, Dominique Bozo, former Director of the Centre Pompidou, once said, “The exactness, the tactile quality of the plaster, the drawing in space. They are miraculous.”

Perhaps the work of Diego Giacometti may never gain the same reputation as the work of his brother Alberto. But it is safe to say neither would have attained what they did without each other. As we rightfully acknowledge the achievements of the more famous of the two, in the spirit of the profound human truths to which his work speaks we should also take a moment to recognize the value of relationships. The relationship these two brothers had with each other, with all of its complexities and inherent dramas, is a reminder of the debt people owe to each other regardless of what it is they are trying to achieve.

Diego Giacometti - Pair of Dompteuse table lamps, Silvered bronze, 19 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 4 3/8 in (49.2 × 18.4 × 11.1 cm)

Diego Giacometti - Pair of Dompteuse table lamps, Silvered bronze, 19 3/8 × 7 1/4 × 4 3/8 in (49.2 × 18.4 × 11.1 cm)

Featured image: Diego Giacometti - Oiseau, ca. 1970, Bronze with brown patina, Lucien Thinot, 4 3/10 × 5 7/10 in (11 × 14.5 cm), Photo credits Helene Bailly Gallery, Paris

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio