Mitchell-Innes and Nash Salutes the Art of Julian Stanczak

Jun 12, 2017

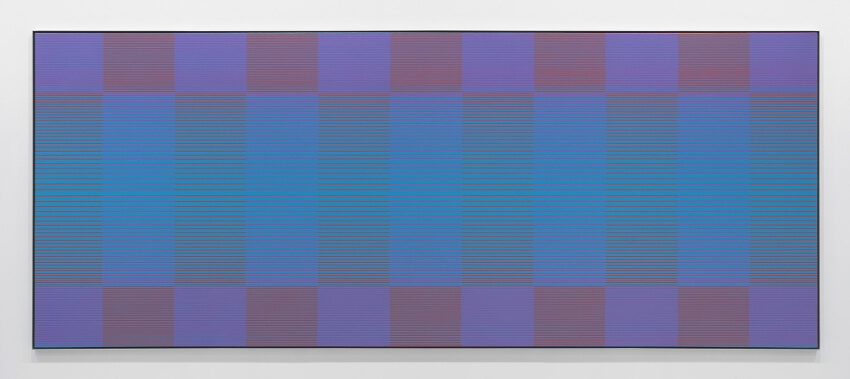

The painter Julian Stanczak died earlier this year in his hometown of Cleveland Ohio, at the age of 88. Prior to his death, Mitchell-Innes and Nash in New York had been planning what would have been the second solo exhibition at the gallery of his work. That exhibition opened on 18 May, less than two months after Stanczak passed, and it has became more than just another show. It is a celebration of the work and the life of a truly beloved and influential artist. The subtitle of the show is The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970-1975. As indicated it features only works made in a five-year period in the 70s. But more importantly is the reference to the life Stanczak brought to his work, and to the art world in general. As one of the progenitors of what eventually became known as Op Art, Stanczak was a pioneer who discovered the extraordinary things that can be accomplished using only the simple elements of color and line.

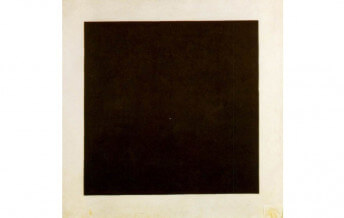

Accidentally Inventing Op Art

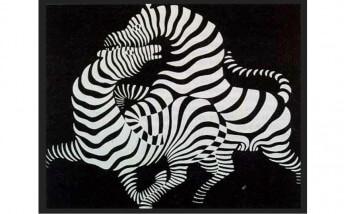

Today the term Op Art is understood by most art lovers, curators, educators and collectors to refer to a kind of trippy, geometric art that tricks the eye into perceiving movement, space and light where none actually exists. The movement is usually tied to a handful of big name artists like Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely, who were, in the early days, its most high profile proponents. And contemporary audiences tend to perceive it as a cohesive movement, one in which the artists involved had an understood agenda, or were at least moving in a cohesive aesthetic direction.

But the truth about Op Art is far less glamorous than that. The term Op Art emerged from the title of an exhibition of the work of none other than Julian Stanczak. The show was his first in New York, and was held at the Martha Jackson Gallery in 1964. Martha Jackson herself titled the show Julian Stanczak: Optical Paintings. When he traveled to New York from his home in Cleveland to see the show, Stanczak learned of the title for the first time when he saw it written on the gallery window. In a 2011 interview, Stanczak recalled, “I said, ‘My God, where do you get that? Martha, how can you say optical?’” Jackson tried to calm him down by replying, “Hey, Julian, this is something for the art critics to chew on.” And chew they did. In fact, a young sculptor named Donald Judd who wrote criticism for Arts magazine at the time, reviewed the show and in reference to its title coined the phrase Op Art in his review.

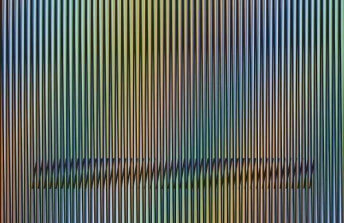

Julian Stanczak - Static Blue, 1973, Acrylic on canvas, 48x120in

Julian Stanczak - Static Blue, 1973, Acrylic on canvas, 48x120in

Color and Line

In retrospect, it does seem ludicrous to single out one particular type of painting and dub it optical. The word optical relates to any phenomenon that exists within the visible spectrum of light. But in the context of the paintings that were included in that first Julian Stanczak show at Martha Jackson Gallery, the term was interpreted not only to refer to what is visible, but rather to have something to do with optical illusions. Stanczak employed the combination of color and line to give the impression of depth and movement, and to suggest that light was emanating from the surface of the work. But nothing about the work was an attempt to fool anyone. It was simply an investigation into the possibilities of what color and line could accomplish on their own.

His initial attraction to the elements of color and line began for Stanczak decades before that first show in New York, when he was a young man in a refugee camp in Uganda during World War II. He had lost the use of his dominant right arm while working in a labor camp then had it further injured by incompetent army doctors. The injury ended his dream of being a musician, so upon arriving in Africa and noticing its beauty and color, he took the opportunity to learn to draw and paint with his left hand. His work from that time is extraordinary, showing that even with his non-dominant hand he possessed an uncommon ability to paint from reality. But he had no desire to paint what he had seen and experienced. He instead sought abstract subject matter that could help him forget the past and paint something universal.

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

Coming to Ohio

As soon as he was able, Stanczak came to America where he joined members of his family who were living in Ohio. He found the city of Cleveland to be well-suited to his artistic ambitions, discovering there a vibrant symphony and art museum. He enrolled in art classes at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, and it was there that he really began to focus specifically on the element of color. But he found out quickly that no one at his school was able to teach him all that he wanted to know. Said Stanczak, “I was enjoying the color. And I wanted to know more about it. And nobody answered my questions. So I heard Albers is an expert. And where is he teaching? Up at Yale. So I go to Yale.”

By Albers, Stanczak was referring to Joseph Albers, one of the foremost Modernist experts in color. Joseph Albers and his wife Anni were influential teachers at the Bauhaus prior to World War II. When the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close, they traveled to North Carolina by invitation to teach at the Black Mountain College. Later they moved on to Yale. Hearing that Albers was the foremost expert on color in the world, Stanczak applied to Yale for graduate work. And while studying under Albers he became assured that indeed everything that he had been longing to express could be expressed with color, along with the simple addition of line.

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

The Responsive Eye

Two years after his first exhibition at Martha Jackson Gallery, the one that led to the coining of the term Op Art, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mounted its ambitious exhibition of geometric abstract art called The Responsive Eye. Julian Stanczak was included in the show, as was his teacher at Yale, Joseph Albers, the fore mentioned Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely, and 95 other artists from 15 countries. That exhibition has since become famous for introducing Op Art to the wider public imagination. But at the time, MoMA never used the term Op Art to refer to the work in the show. Instead the museum used terms like perception to highlight their exploration of the new ways artists were using geometry, color, surface, line and light to examine how people see.

As William C. Seits, who directed The Responsive Eye exhibition, said in the press release for the show, “these works exist less as objects to be examined than as generators of perceptual responses in the eye and mind of the viewer. Using only lines, bands and patterns, flat areas of color, white, gray or black or cleanly cut wood, glass, metal and plastic, perceptual artists establish a new relationship between the observer and a work of art. These new kinds of subjective experiences...are entirely real to the eye even though they do not exist physically in the work itself.” The Responsive Eye gave an enormous boost to the career of Julian Stanczak, as well as to many other artists in the show. But Stanczak did not move to New York, where he easily could have enjoyed immense fame. Instead, he remained based in Cleveland, where he served as a painting professor for 38 years at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes and Nash NY, 2017

Remembering Julian Stanczak

From his home in Cleveland, away from the art world capitals, Stanczak continued exploring color and light in his paintings for the rest of his life. His painstaking process of laying down layers of paint with his non-dominant left hand was time consuming and laborious. But in his process he found joy and release, both of which emanate in droves from his work. Over the decades his paintings were acquired by almost 100 museums around the world, though he was all but ignored by galleries in New York.

But finally in 2004, Stanczak returned to New York with back-to-back solo shows at Stefan Stux Gallery. And over the next decade he appeared in several group shows in the city, gradually once again becoming prominent in the minds of the art-buying public. Then in 2014, he was given his first exhibition at Mitchell-Innes & Nash. The current posthumous exhibition of his work is perfectly sub-titled, as Stanczak indeed spent a lifetime bringing life to the surfaces of his paintings. It only runs through to 24 June 2017, so hurry if you would like to see it. But if you miss it, do not fret. As the world realizes the genius it has lost, it will likely only be the first exhibition to celebrate the legacy of this master of color and line.

Featured image: Julian Stanczak - The Life of the Surface, Paintings 1970 – 1975, installation view at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, NY, 2017

All images courtesy of Mitchell-Innes and Nash

By Phillip Barcio