Here are Some Brilliant Examples of Cubist Sculpture

In painting, Cubism tends to flatten space, so at first glance perhaps the idea of Cubist sculpture may seem like a contradiction. But the theory behind Cubism isn’t about dimensionality so much as it’s about simultaneity, freedom from depicting a single vantage point at a specific moment in space and time. In practice, the theoretical aspects of Cubism present exciting challenges to sculptors. That’s why from the earliest stages of the movement’s development Cubist sculpture was actively explored both by devoted, full time sculptors as well as painters who were intellectually drawn to the medium by Cubism’s radical approach to depicting geometry, movement, perspective and time.

Early Cubist Sculpture

It’s no surprise that most art historians consider the first Cubist sculpture to be a work by Pablo Picasso, the inventor of Cubism. Picasso’s proto-Cubist painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon was painted in 1907, and is considered to be the starting point for Cubist theory. Picasso’s first Cubist sculpture was created in 1909, and was titled Woman’s Head (Fernande). The sculpture was of his lover Fernande Olivier. It consisted of a variety of different planes and utilized a simplified geometric vocabulary, as though piecing together surfaces seen from a multitude of vantage points. The work is essentially Cubist in that it strives to show multiple aspects of the subject simultaneously shifting in volume and presence as though moving through time. Originally cast out of clay, with Picasso’s permission it was later cast in bronze.

Pablo Picasso - Woman’s Head (Fernande), 1909. Bronze. 41.3 x 24.7 x 26.6 cm. © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights, Society (ARS), New York

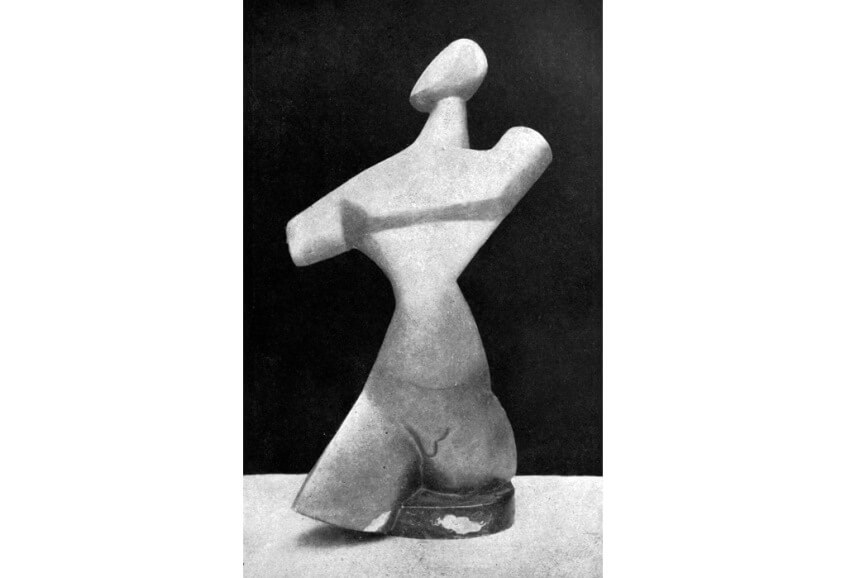

About one year later, the Ukrainian-born sculptor Alexander Archipenko devoted himself fully to expressing Cubism through sculpture. The Hero (1910) is one of his earliest efforts, presenting the simplified geometry of a male human form in motion. In the following years, Archipenko’s practice evolved into far more elaborate examinations of Cubist forms, as he attempted to convey a multitude of different points of view while reducing forms to their simplest geometric equivalents, as is represented in pieces like Woman Walking, from 1912.

Alexander Archipenko - Heros, 1913. Gelatin silver print. 14.7 x 11 cm (5.8 x 4.3 in.).

Alexander Archipenko - Heros, 1913. Gelatin silver print. 14.7 x 11 cm (5.8 x 4.3 in.).

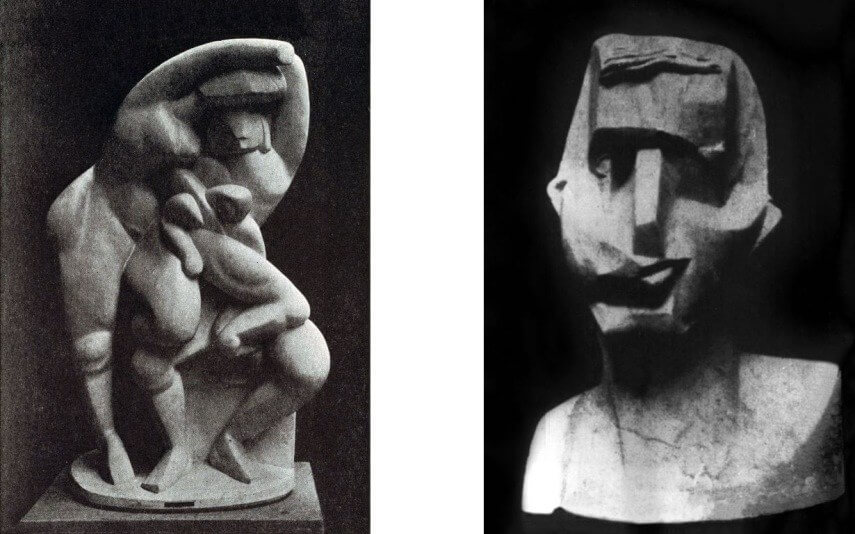

The Lost Cubist Sculptures

Archipenko’s work was considered groundbreaking and was included in the seminal Cubist exhibition at the 1912 Salon d'Automne in Paris. At the show, he exhibited a sculpture called Family Life. The work represents a brilliant point in his development, but is listed as having been accidentally destroyed. Strangely the same fate befell several other early Cubist sculptures, including Joseph Csaky’s Groupe de femmes (also included in the1912 Salon d'Automne) and Csaky’s Head (self-portrait).

Alexander Archipenko - Family Life, 1912 (Left) and Joseph Csaky - Head - Self-Portrait, 1913 (Right)

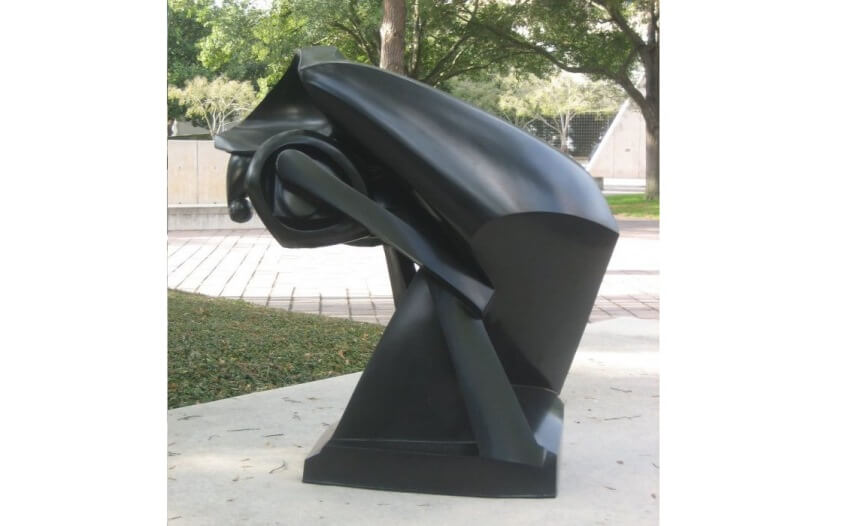

Moving Through Time

It’s evident from looking at the works of the earliest Cubist sculptors that their concerns were mostly focused on capturing multiple vantage points, representing points of view as they shift across multiple surfaces and in reducing their formal vocabulary to simple geometric shapes. But great Cubist sculpture should also be focused on movement and time, capturing the mobility of a subject as it turns and twists in an active, dynamic way.

One brilliant example of Cubist sculpture that captures simultaneity, geometry and movement through time is The Large Horse (1914), by Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Raymond was one of four Duchamp children who became successful professional artists. He was an expert on horses, having served in a military cavalry division. The Large Horse captures the power and grace of a horse charging and leaping through space.

Raymond Duchamp-Villon - The Large Horse, 1914 (cast c. 1930-31). Bronze. 101.6 x 100.1 x 56.7 cm. MoMA Collection

Duchamp-Villon’s work had a powerful impact on the Italian artist Umberto Boccioni , who became a major figure in the Futurist movement. Boccioni was intent on capturing motion in his sculptures. His aim was not to abstract the forms he was sculpting, but rather to represent their essential nature by capturing their movement through space and time. Said Boccioni, “We are not against nature…(we’re) against immobility.”

Line, Plane & Volume

The Lithuania-born sculptor Jacques Lipchitz explored a novel approach to Cubist sculpture sparked by the conversation Picasso started in 1912 with his earliest assemblages. The idea of an assemblage is that instead of arriving at a sculptural form through the reduction of mass, you assemble a three-dimensional form through disparate parts. Lipchitz modified that concept to fit into his sculptural practice.

Describing his sculptures as “architectural,” he saw himself as building the human form, first reducing its parts down to the simplest manifestations of surface, line and volume and then assembling those disparate parts into a multi-perspective whole. The quintessential example of his thinking manifested in a work from 1915, simply titled “Sculpture.”

Less theoretical and more visceral in approach, the sculptor Henri Laurens similarly constructed voluminous human forms using a reduced language of cylinders, cones, towers and orbs resting on a multitude of surfaces seen from various perspectives. Laurens began sculpting in 1915. His work Femme au Compotier, from 1920, demonstrates Lipchitz’s architectural influences.

Henri Laurens - Femme au Compotier, 1920. Terracotta. 36.8 cm (14.5 in.).

The Czech Cubist Tradition

Among the earliest Cubist sculptors were two artists from Prague, each of whom studied in Paris before World War I. For these artists, Cubism was a powerful philosophical force. The intellectual freedom it embodied was unlike anything they had encountered back home. The Czech sculptor Otto Gutfreund came to Paris in 1909 and Emil Filla was a multidisciplinary artist who came to France periodically between 1907 and 1914.

Filla and Gutfreund both fought in the Netherlands during World War I then returned to Prague after the war. Filla became an art instructor. Gutfreund brought back with him a passion for the work of Picasso and Georges Braque, writing of Cubism’s ability to “condense an entire abundance into each view.” Cubism profoundly affected these two Czech artists, who in turn profoundly influenced the future of their nation’s artistic development.

Otto Gutfreund - Holding Each Other, 1913-14. Bronze. 25 x 13 x 10 inches. National Gallery, Prague and Emil Filla - Cubist Head, 1913.

The Legacy of Cubist Sculpture

Though most sculptors had evolved into new forms of expression by the mid-1920s, Cubism had made a dramatic impact on the thinking of all artistic disciplines. Current sculptural traditions may not rely on the geometry or aesthetics of Cubism, but the quest to portray movement, time and multiple perspectives went on to influence many other art movements. Perhaps Cubist sculpture’s most important legacy is just that: its innovation, and in the freedom it gave artists to strive for new ways to represent the entirety of the human experience.

Featured Image: Alexander Archipenko - Woman Walking, 1912.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio