Early Abstract Art as the Visual Embodiment of an Idea

One of the ironies of early abstract art is that so many people suspected it of being haphazard, random or meaningless. Viewers conditioned to accept only objective representations of the material world were baffled by a new generation of artists who, as Wassily Kandinsky put it, sought to express “ideas which give free scope to the non-material strivings of the soul.” We now know that from the beginning of abstract art, its practitioners were engaged in anything but random gestures. They were making reasoned and conscious aesthetic choices in an attempt to convey the philosophical grounds on which the philosophy of abstraction was based.

Early Abstract Art vs. The Past

Prior to abstraction’s rise, any reasonable art lover expected a good painting to possess at least some recognizable element of the real world. Viewers could accept an artist taking steps to abstract recognizable elements. They could even sometimes accept an almost entirely unrecognizable painting, as long as its name gave some clue as to the object from which it was abstracted. But the notion of a purely abstract painting, one with no recognizable correlation to visual reality, was considered absurd, if not heretical.

Wassily Kandinsky was the first artist to fully embrace the idea of pure abstraction. He believed humanity’s fundamental truths and universal ideas couldn’t be discovered through representation of the material world. He believed objects were of no use to artists trying to express humanity’s inner depths. In 1912, Kandinsky published his seminal book, “Concerning The Spiritual In Art,” which laid out the philosophy guiding his search for a purely abstract art. In it he wrote:

"Shapeless emotions such as fear, joy, grief, etc., will no longer greatly attract the artist. He will endeavour to awake subtler emotions, as yet unnamed…lofty emotions beyond the reach of words."

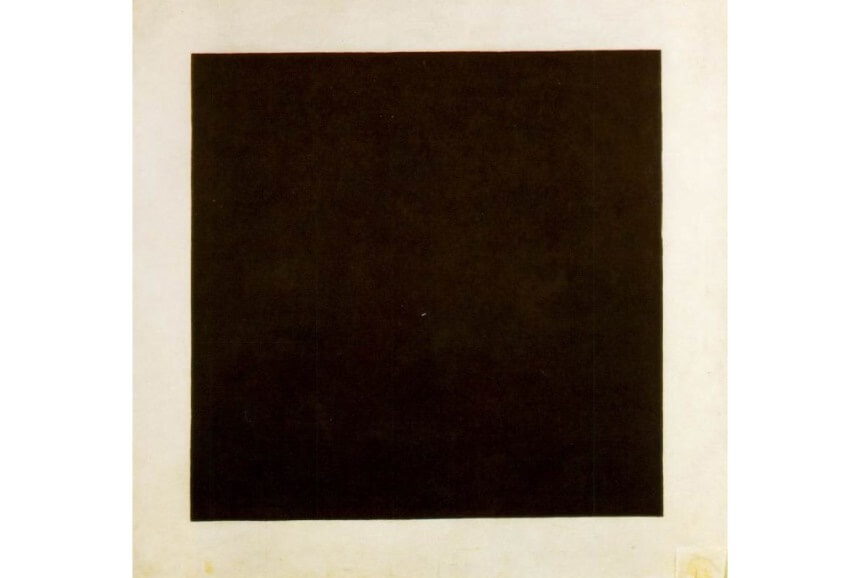

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915, oil on linen, 79.5 x 79.5 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The Search for Pure Artistry

Looking back over art history, Kandinsky believed that previous generations had mostly focused on communicating with themselves and expressing the personality of their time. He believed abstract artists should seek to express the essential similarities each human being has to all other human beings, regardless to which era they belong. He called these similarities humanity’s “inner sympathy of meaning.”

Kandinsky believed the source of this meaning was the human soul, or what he called the “Inner Need.” He felt the inner need could be expressed through pure artistry, so long as it was free of ego and materialist viewpoints. As he put it:

“That is beautiful…which springs from the soul.”

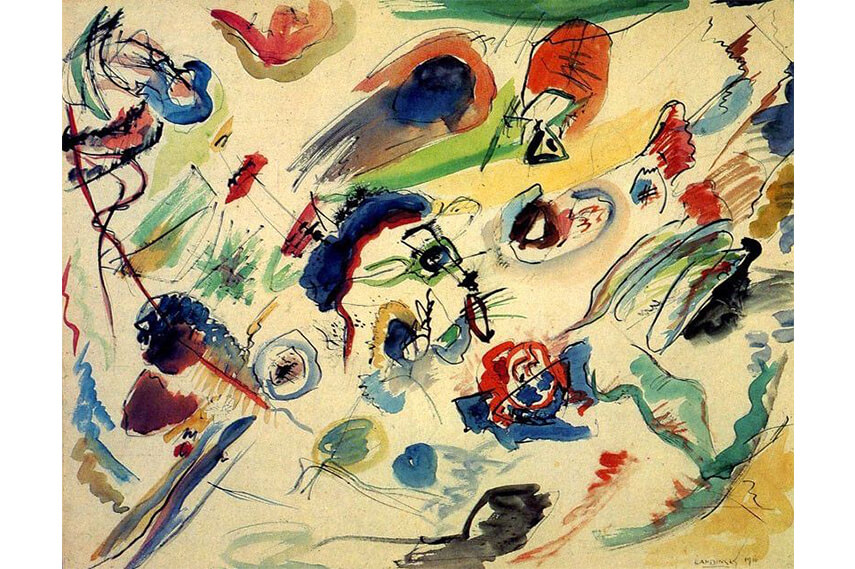

Wassily Kandinsky - Kandinsky's first abstract watercolor, 1910, Watercolor and Indian ink and pencil on paper. 19.5 × 25.5 in (49.6 × 64.8 cm) Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

Music as a Model

Kandinsky believed music was the art form most adept at communicating “emotions beyond the reach of words.” He wrote:

"A painter…in his longing to express his inner life, cannot but envy the ease with which music, the most non-material of the arts today, achieves this end.”

He recognized that composers had successfully deconstructed music to its simplest parts, identifying how a composition’s individual elements could affect the human spirit. He began deciphering painting’s elements in the same way, for example attempting to define each color’s individual effect on viewers. Kandinsky even borrowed words from music’s lexicon to help explain his outlook on abstract art. He called paintings compositions, and recommended artists carefully construct their compositions through reasoned choices. He simultaneously called on artists to leave room in their compositions for improvisation, which he called the “spontaneous expression of inner character.” He believed that through consciously constructed abstract work, painters could become “great spiritual leaders,” and could finally succeed in expressing the human spirit’s fullest potential through art.

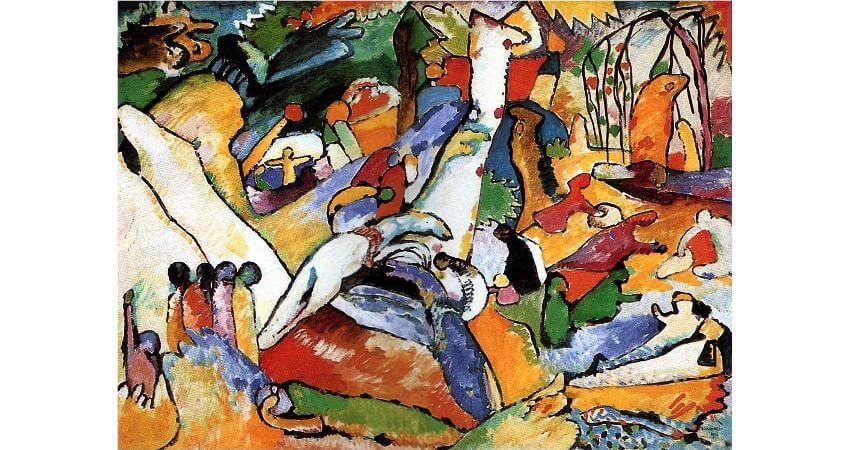

Wassily Kandinsky - sketch for Composition II, 1910, 38.4 × 51.4 in (97.5 × 130.5 cm), The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Abstract Art vs. the Future

In his foreword to Kandinsky’s “Concerning The Spiritual In Art,” the British historian Michael Sadler wrote:“If (Kandinsky) ever succeeds in finding a common language of colour and line which shall stand alone as the language of sound and beat stands alone…he will on all hands be hailed as a great innovator, as a champion of the freedom of art.” Looking back on more than a century of abstract art, we see that Kandinsky achieved his goal. Gratefully, we also see that he laid the foundation for our, and innumerable future generations to build upon his philosophy, searching for new ways to express “lofty emotions beyond the reach of words."

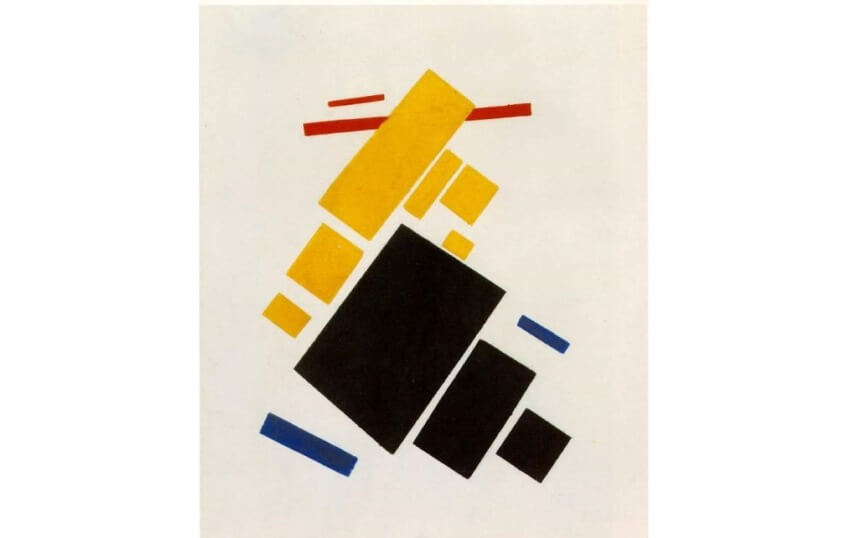

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematism: Painterly Realism of a Football Player (Color Masses in the Fourth Dimension), 1915, Oil on canvas, 27 x 17 1/2 in, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Featured image:Hilma af Klint - The Swan, No 17, Group IX, Series SUW 1914-1915, © Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

All images used for illustrative purposes only