Inside - And Outside - Ellsworth Kelly’s Pavilion in Austin

Feb 16, 2018

A new destination for art pilgrims has just been added to the American Southwest—Ellsworth Kelly: Austin. Located on the grounds of the Blanton Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Texas, Austin, this monumental stone structure is the final work Kelly made before he died. It is designed as an aesthetic refuge—a non-denominational, meditative, architectural art environment. In its function, as well as in its physical essence, it is a natural addition to this geographical region, which has long been a popular destination for aesthetic wayfarers. Like the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, which features multiple custom paintings Rothko created just for that space, Austin includes an assortment of custom paintings and one sculpture, which serve less as objects, and more as transcendental points of departure. And like the Dwan Light Sanctuary in Las Vegas, New Mexico, which mobilizes prismatic windows to create a kinetic light and space chapel, Austin mobilizes the windows of the building to transform daylight into nomadic beams of color that meander across the space—promising a subtly new experience to viewers every time they enter. Austin is already being hailed as a masterpiece, and perhaps the greatest work Kelly ever made. But there is also something challenging about it. Namely, unlike either of those other aforementioned art refuges, Austin engages with religious symbolism in a direct way that could be a contentious cause for conversation for generations to come.

Symbolically Speaking

Ellsworth Kelly was a self-proclaimed atheist. As he told Interview magazine in 2011, “I am not even a doubter. I am an atheist.” But Kelly was not antagonistic toward religious beliefs and traditions, nor to those who upheld them. He simply figured that people would be able to think more clearly if they left their fundamentalism behind. But he did often feel drawn to churches, temples and spiritual destinations of all different kinds. And he also drew them. He admired their shapes, and the layouts of their interior spaces. And in particular, he was interested in the ways people interact with art within spiritual buildings. One of the earliest experiences he had with religious art was when his parents sent him to Sunday school as a child. That is where he first encountered the Stations of the Cross. For those uninitiated, the Stations of the Cross are 14 artistic representations of Jesus of Nazareth, depicting his suffering during his condemnation and execution.

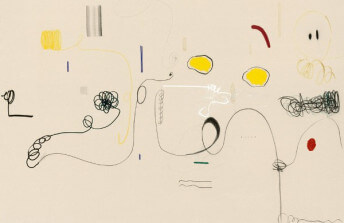

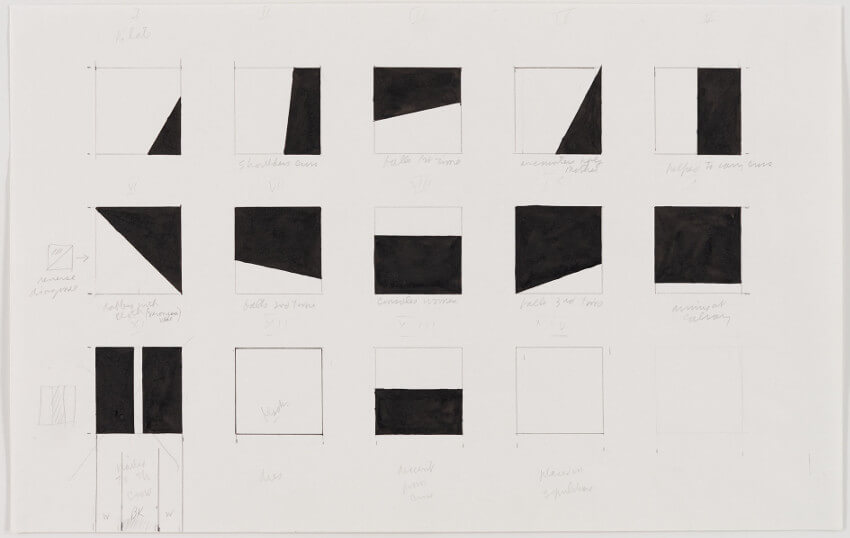

Ellsworth Kelly - Study for Stations of the Cross, 1987, ink and graphite on paper, 12 1/2 x 19 inches, © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation; Photo Ron Amstutz, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Ellsworth Kelly - Study for Stations of the Cross, 1987, ink and graphite on paper, 12 1/2 x 19 inches, © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation; Photo Ron Amstutz, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Inside Austin, hanging on the walls, are fourteen marble panels Kelly made based on his 1987 drawing, Study for Stations of the Cross. Rather than depicting images of Jesus in his suffering, each of these panels conveys a black and white geometric structure. And they are not the only reference to Christianity in this space. The building itself is cross shaped. Three of the four cross sections feature these marble paintings on the walls. In the fourth, where the altar would be in a Christian church, stands a wooden “totem.” Kelly has been making totems since the 1970s. They are placed in many different spots, are all similarly, vertically shaped, and are made out of a variety of materials. This one happens to be made of redwood, a conifer, same as the trees from which the wooden cross Jesus was nailed to was made.

Ellsworth Kelly - Austin, 2015 (Interior, facing south). © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin.

Ellsworth Kelly - Austin, 2015 (Interior, facing south). © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin.

Believe What You See

What Kelly was intending to say with the obvious Christian references in Austin is unknown. But the closest Kelly came to believing in something spiritual himself was to believe in nature. He said, “I feel this earth is enough. Look up at the sun. It is millions of years old and still to be millions more. And then there are all the spaces we can never see.” Throughout his life, Kelly portrayed his artistic practice as a method of trying to get people to perceive things differently. He wanted us to look, and then look again, and then to think about what it is we see and feel. Some people may see Austin as a challenge to Christian symbology. Some may see it as an overtly religious space, no different than any other church. I see it as an invitation to challenge the meaning and importance people put on things like symbols, objects, materials and buildings.

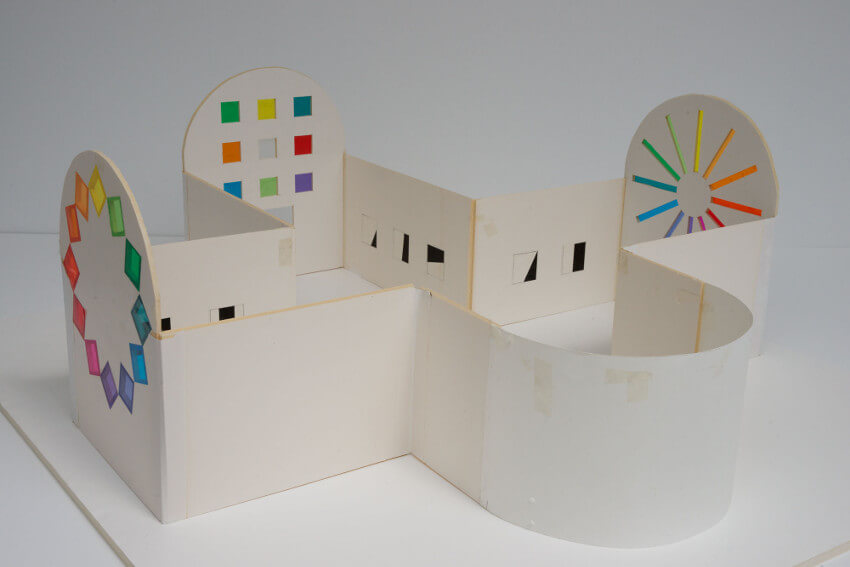

Ellsworth Kelly - Model for Chapel, 1986, mixed media, 14 ½ x 36 ¼ x 40 inches, © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Photo courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

Ellsworth Kelly - Model for Chapel, 1986, mixed media, 14 ½ x 36 ¼ x 40 inches, © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Photo courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio

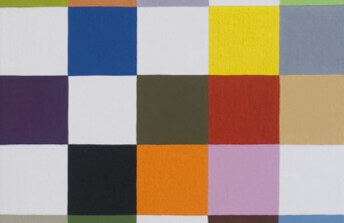

The one aspect of Austin that is kinetic—which retains a sense of life—is the light. Three of the four extremities of the building contain blown glass, colored windows. On the main facade are nine square windows, a continuation of a common aesthetic theme Kelly pursued—colored squares in a grid formation. The other two walls feature 12 colored glass windows arranged like the markings of a clock. On one wall they are linear, and on the other they are square. To me this makes me think about how symbols and material possessions are ultimately barren, stoic things. Only nature is capable of change. To me, the beauty and power of Austin is that it offers me a chance to see the rotation of the planet in action. It shows me the hands of time as they interact with the light of the sun. It inspires me to look, to think, and to feel. To me, these things are fundamental, but they are as far from fundamentalism as it is possible to get.

Featured image: Ellsworth Kelly - Austin, 2015 (Southeast view), © 2018 Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio