How Enid Marx Redefined the 20th Century Design

Jul 25, 2018

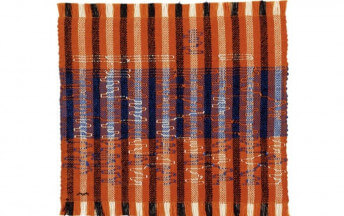

Enid Marx was only 26 years old in 1928 when Virginia Woolf wrote the famous line: “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” But indeed, even at that young age, Marx knew exactly what Woolf meant. Much of the work that Marx would go on to create over the course of her seven decade long career would be done in anonymity. In the 1920s and 30s, female designers in the UK were not normally given the chance to open their own design firms. They tended to freelance for male designers, or join workshops where they were frequently not credited for their designs. Nonetheless, through a mixture of ingenuity, genius, and constant hard work, Marx beat the odds and made an international name for herself. In fact, she went on to create such beloved designs that in 1937 her work literally began to pervade the very fabric of British society, as she was selected by The London Passenger Transport Board to help redesign the seat covers for the London busses and subway trains. At least four of her designs were used on the Tube, meaning that for decades, whether they realized it or not, few mid-20th Century riders of this most famous of subway systems were not touched by her work, if only on their hind quarters. The extensive and diverse legacy Marx created was recently memorialized in the first ever monograph of her work, titled Enid Marx: The Pleasures of Pattern. Coinciding with the release of the book, the House of Illustration in London also opened Enid Marx: Print, Pattern and Popular Art, the largest and most complete exhibition of her work to be mounted in half a century. Featuring more than 150 items, this joyful retrospective is a reminder of the massive influence Marx had over the visual lexicon of 20th Century Britain, even if many people who adored her designs had no idea they were hers.

Vulgar, And Proud Of It

In addition to designing fabrics for bus and subway seats, Marx also created countless other designs and illustrations that inundated the daily life of people mid-20th Century England. Her work appeared on wallpaper, postage stamps, the covers of more than half a dozen popular books, to name just a few examples. Yet her professors at the Royal Academy of Art never would have predicted that her designs would become so ubiquitous. In fact, they judged the work Marx did to be “vulgar” during her final assessment, evidently because of the modernity of her designs, and they failed her because of it. Marx did not hesitate, however, to ignore their judgment. She followed her own creative vision, walked away from the Royal Academy, and entered professional life, self-assured that her ideas were in line with the fashions and tastes of the market even if the older generation was too lodged in the past to realize it.

Enid Marx exhibition view at House of Illustration. © Paul Grover. Courtesy House of Illustration, London

Immediately after leaving the RCA, Marx found commercial success in multiple different fields. She worked as a textile designer and found representation for her artworks in two galleries in London. She designed book covers and created decorative papers for commercial printers. She also worked as a designer for Chatto & Windus, a major British publisher that is today owned by Random House. And all of this was before being hired to create designs for the Transport Board. Later on, Marx would also create watercolors of threatened buildings during World War II, and help to establish war-time austerity protocols in the furniture design industry. After the war, she was named Royal Designer for Industry by the Royal Society of Arts, becoming the first female engraver ever to be given the title. Marx even eventually became an academic, serving for five years as a Department Head at the Croyden School of Art. How gratifying it must have been to her when, in 1982, the RCA finally acquiesced and awarded Marx with an honorary degree, admitting in the face of undeniable proof that it was they who had failed her and not the other way around.

Enid Marx exhibition view at House of Illustration. © Paul Grover. Courtesy House of Illustration, London

Beacon of Modernism and Abstraction

As Enid Marx: Print, Pattern and Popular Art demonstrates, despite her many accomplishments, perhaps the most influential thing Marx managed was inspire in the public a wide general appreciation for the visual theories of Modernism and Abstraction. She had a sophisticated understanding of the value that geometric patterns and color relationships have in creating soothing, pleasant, and rejuvenating public visuals, and she had a knack for deploying her knowledge in the everyday realm. Her book designs incorporated a mixture of abstract and figurative images. Deftly switching from one to the other, she communicated something essential to viewers: that abstraction can be as valid and communicative in as figuration. She proved that it is formal aesthetic elements, not narrative content, that matters most when it comes to projecting a public mood.

Enid Marx exhibition view at House of Illustration. © Paul Grover. Courtesy House of Illustration, London

In fact, mood is the main characteristic of this current exhibition. The works on view show that Marx always managed to capture the mood of her time, and to convey it succinctly. Each design declares the age in which it was made. Those from the 1920s and 30s convey the futuristic, industrious optimism of early abstraction. Her works from after World War II communicate an almost naive childlike longing for beauty and hope. Always, Marx had an unwavering sense of what the public needed, and how to offer it through industrial design. Yet all of this she did with modesty and humility, claiming that she was not really very original, but was simply channeling what was all around her in the air. Even if she believed that was true, she had a special knack for translating what was already in the culture into a voice that the public now instantly recognizes as her own. Enid Marx: Print, Pattern and Popular Art is on view at the House of Illustration through 23 September 2018.

Featured image: Enid Marx exhibition view at House of Illustration. © Paul Grover. Courtesy House of Illustration, London

By Phillip Barcio