A Museum in Tasmania Gathers the Founders of the Zero Art Movement

Australian art collector and gambling magnate David Walsh recently opened a landmark exhibition of the Zero art movement at his Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) in Hobart, Tasmania. Titled ZERO, the exhibition features works by 16 artists from seven countries, several of which have been installed for the first time ever since their debut more than half a century ago. Providing even more drama for visitors, and more incentive to make the trip to this remote locale, is the environment in which this monumental exhibition is taking place. MONA is mostly underground. The building is constructed several stories beneath a pair of landmark buildings by the Australian Modernist architect Roy Grounds. Unlike most other museums, which welcome natural light and strive to make visitors feel they are in an open, welcoming space, MONA is decidedly unnatural, and at times even a bit unwelcoming. Upon entering, visitors descend into a somewhat alien environment where the force of the architecture often competes with the art it is intended to support. Yet the space also drives viewers to seek comfort from each other, and from the work. In a way, the setting is ideal for showcasing the work of the Zero artists, as it embodies two of their essential ideas: that art is about possibilities and the unknown, and that it should involve real experiences between people, materials, and space.

Saved By Zero

The Zero movement was founded by Heinz Mack and Otto Piene in 1957 out of a desire to begin anew. Like many of their contemporaries, Mack and Piene were striving to escape the past, and to get away from the egotism and emotion that had taken control over so much of the art of their time. In Düsseldorf, where they lived and worked, there were few art galleries. And elsewhere, the tastes of the market tended towards artwork that expressed a sort of “cult of individuality,” epitomized by aesthetic positions that expressed personal emotion, such as Tachisme, Art Informel, and Abstract Expressionism. Mack and Piene regarded collaboration as more important than individualism. They believed the value of art was in the experience that it could instigate between makers, viewers, materials, and environments. They felt that the traditional, singular, artist-made object was dead, and they wanted to instigate a new starting point from which they could allow the future to take root.

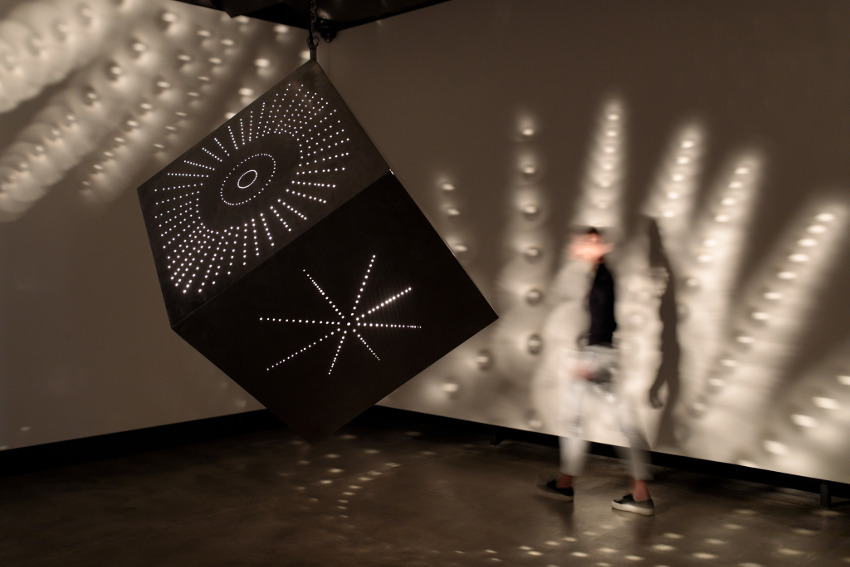

Otto Piene - Pirouetten (Pirouettes), 1960s; recreated in 2012. Collection More Sky © Otto Piene. VG Bild-Kunst/ Copyright Agency, 2018. Image courtesy Museum of Old and New Art (Mona)

Mack and Piene held their first exhibition of what they considered to be the future of art on 11 April 1957, in their studio. It was a one-night affair intended to embrace ephemerality. The show generated immense interest, and was quickly followed by several more experiential, one-night exhibitions. But it was not until after their fourth exhibition, in September of 1957, that they came up with the word Zero to describe their collaborative. The word was intended to convey the idea that the past had officially ended—it was a starting point for the future. As Piene described it: “We looked upon the term...as a word indicating a zone of silence and of pure possibilities for a new beginning as at the count-down when rockets take off—zero if the incommensurable zone in which the old state turns into the new.”

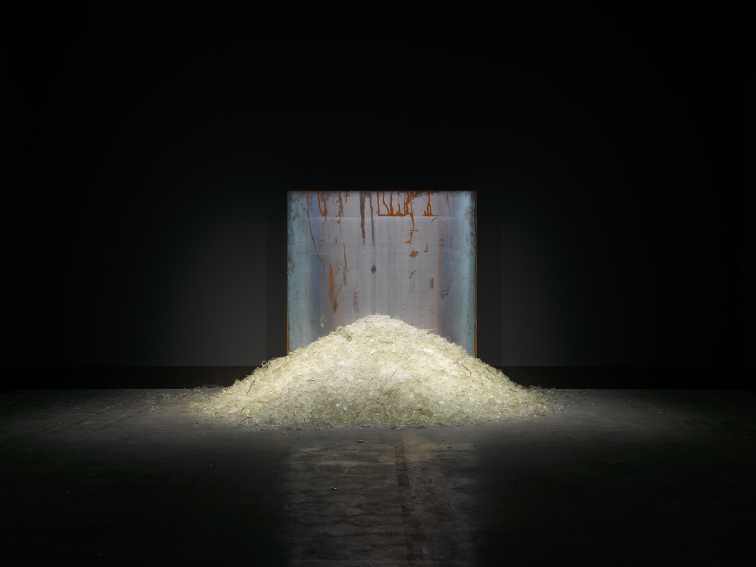

Adolf Luther - Flaschenzerschlagungsraum, (Bottle Smashing Room), 1961; recreated in 2018. Collection Adolf Luther Stiftung, Krefeld. Copyright: Adolf Luther Stiftung. Image courtesy Museum of Old and New Art (Mona)

ZERO, not Zero

Despite the openness of the movement, Mack and Piene did have one strange conceit. They stipulated that when writing about them, the founders should be referred to as “Zero,” while other associated artists should be referred to as “ZERO.” This is why the exhibition at MONA uses all capital letters—because it mostly features works by the larger international network of artists who associate with the philosophy. Nonetheless, as ZERO at MONA makes clear, there were no outsiders in the movement. All were welcome. There was no Zero manifesto, and there was no official membership. This attitude resulted in a vast range of work being created by ZERO artists, embodied in this exhibition by the recreation of such landmark ZERO works as “Bottle Smashing Room” (1961) by Adolf Luthor, and “Mirror Environment” (1963) by Christian Megert. The welcoming attitude of the movement is also demonstrated in this exhibition by the inclusion of artists from the many other international movements that Zero helped inspire, such as the Gutai Group in Japan, to Nouveau Realism in Paris, to Light and Space in the United States, to the international movement known as Fluxus. Demonstrating these connections are rare works by Marcel Duchamp, Roy Lichtenstein and Yayoi Kusama, for example, which highlight aspects of their practice that are far different than the work for which they are mostly known.

Roy Lichtenstein - Seascape II, 1965. Collection Kern, Großmaischeid. Copyright: Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/Copyright Agency, 2018. Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Old and New Art (Mona)

One of the most important aspects of this exhibition is that it re-focuses contemporary attention on the need to renew contemporary art. Even though the founders of Zero officially disbanded in 1966, the movement they started has never really ended. And this exhibition also hints at something even more important: the idea that perhaps the Zero art movement never really began. It was perhaps not a movement that was invented in one place at one time, but was really rather part of a much larger continuum that stretches back infinitely, to the first moment that humans desired to use visual phenomena to reach beyond themselves towards something pure, and new. The works in ZERo at MONA are so fresh, and so vital, even now, that they inspire me to believe that ZERO might even continue today, whenever groups of artists get together to collaborate on aesthetic creations that go beyond what is expected, or what is already known. At this moment, in fact, this exhibition and the message it sends is essential. It reminds us of that key tenet of Zero art: that art is about experiences, and relationships between people, their environment, and their collaborative efforts to imagine a better future. ZERO at MONA is on view through 22 April 2019.

Featured image: Gianni Colombo - Spazio elastico, (Elastic Space), 1967–68. Collection Gianni Colombo Archive, Milan © Gianni Colombo Archive. Image courtesy Museum of Old and New Art (Mona)

By Phillip Barcio