Tribute to François Morellet: The Legacy in Abstract Geometry

When an artist dies a light turns off. Not many of us have been lucky enough to personally encounter the work of François Morellet. In fact, even among abstract art lovers the name Morellet is barely known outside of France. But he was a powerful, strange and beautiful source of energy and illumination. Morellet’s work transcended labels as well as cultural and intellectual barriers. Like few other artists have ever managed to do, he combined artistic profundity with a rigorous mastery of craft and a playful sense of humor. Morellet’s light turned off on May 11th, 2016, in his hometown of Cholet, France. He was 90 years old.

The Humor of François Morellet

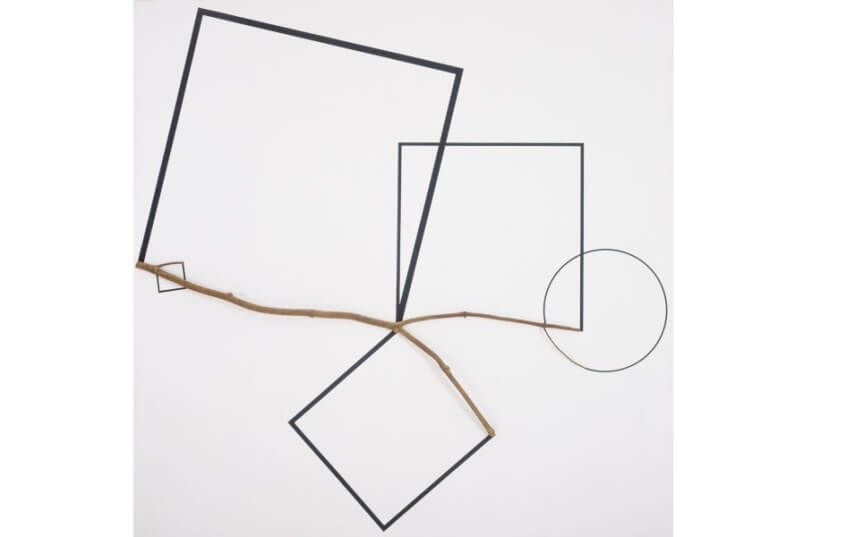

Things are not what they seem. They are much, much more than that, a fact so beautifully and comically illustrated by much of Morellet’s work. Take for example his Geometree series. These playfully profound works are part painting and part-assemblage. In each one, Morellet connects a section of a tree branch to a two-dimensional plane and then explores the ways geometry might extend outward from it. Like tendrils of science, squares, triangles and circles shoot from the branches’ various tips, climbing into a flattened universe. It’s impossible not to smile when considering the eternal invisible geometry all around us, to which these works bring our attention.

Since Morellet has died, a handful of memorial articles have appeared online reflecting on his life and work. One compares his “provocative stance and humor” to the Dadaists . But something is woefully inaccurate about such a comparison. Dada was born from frustration and despair. It saw humanity as absurd. It was a cynical outlook expressed with outrage. François Morellet did make jokes, as evident in the names he gave his works. But the jokes weren’t absurd; they were wry and self deprecating. The attention to detail he gave to each object he created reveals him as someone who cared deeply about those who might encounter what he made. And his sense of wit and contextual awareness of space reveal him as someone with respect for environments and their inhabitants. Morellet was provocative, yes, and humorous, definitely, but he was also sincere, and he was a joyful participant in the world. He was no Dadaist.

François Morellet - GEOMETREE NO. 51, 1984, 1984, Acrylic on canvas with branch, 200 x 200 cm, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo © ARS, NY

François Morellet - Seven Corridors, 2015, Val de Marne Museum of Contemporary Art

Moving and Shaping

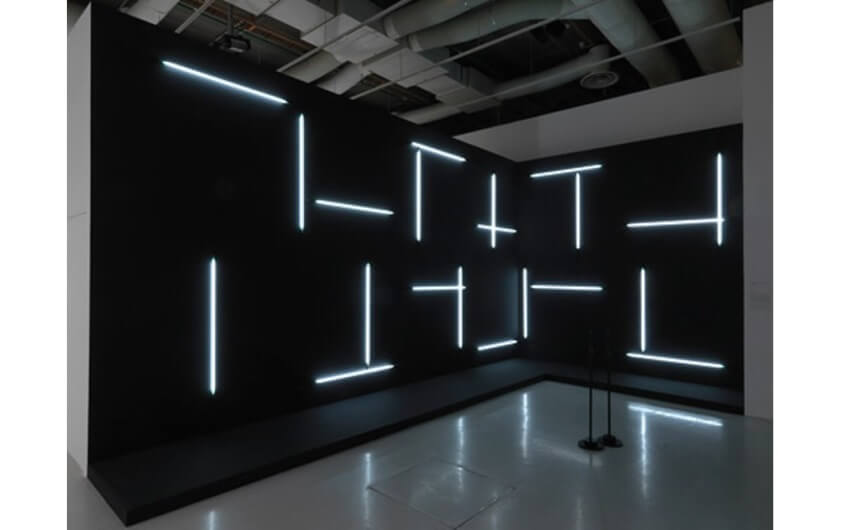

So then what was Morellet, if not a late-blooming Dadaist? Most historians would describe Morellet as a Kinetic Artist, a Geometric Abstractionist, and possibly a proto-Minimalist, labels easily supported by certain elements of his oeuvre. But Morellet also believed strongly in the primary importance of ideas, which made him a Conceptual Artist. And his work with neon and the manipulation of lighting he engineered in many of his exhibition spaces closely aligns him with the Light and Space Movement. Still other pieces are brilliant, iconic examples of Installation Art, such as his 2015 Seven Corridors installation.

And what about Morellet’s seminal 1964 work Reflections in water deformed by the spectator? In this piece he built a geometric neon sculpture and hung it from the ceiling over a black pool of water. Then he invited the public to come and disrupt the water by manipulating a mechanism in the pool. The disturbed water caused the reflection of the lights to become deformed. He then photographed and filmed the disrupted images of the reflected lights. In this single piece, he is a sculptor, a photographer, a light and space artist, an installation artist, a conceptual artist, a geometric abstractionist, a kinetic artist and a minimalist.

So what was Morellet? Was he multi-styled? Was he multi-disciplinary? Perhaps yes and yes. Yes he expressed himself in two, three and four-dimensions. Yes he used geometry, kinetics, ideas, light and space and relied on a pared down, minimal visual language. But it is arguable that he, like Picasso, Yves Klein, Joan Miró or Joseph Beuys, simply defied being labeled at all.

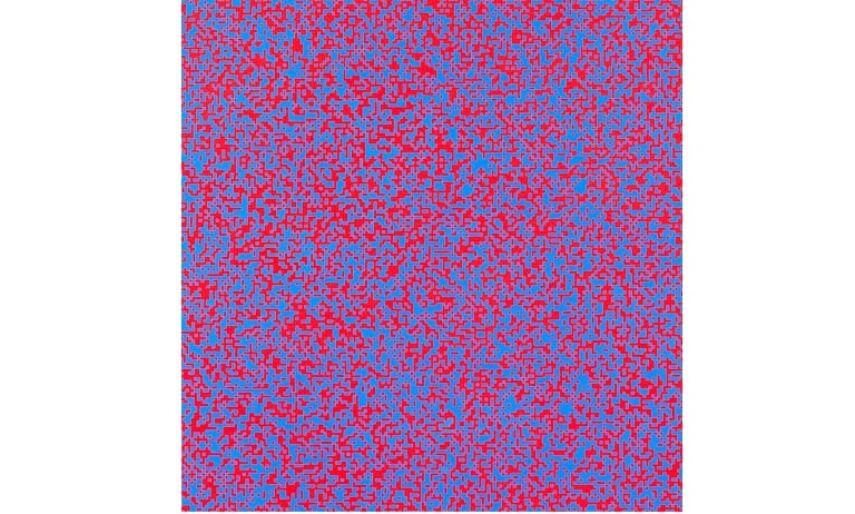

François Morellet - Random Distribution of 4,000 Squares using the Odd and Even Numbers of a Telephone Directory, 1960, Oil on canvas, 103 x 103 cm

François Morellet - 2 frames dashes 0° -90° with audience participation, 1971, White neon tubes, switch

A Legacy of Ambiguity

Looking over the enormous body of meticulously crafted, undeniably beautiful work Morellet created, it appears in retrospect that even the label of “abstract artist” can be seriously called into question. As a young artist, Morellet most definitely shifted away from being a figurative painter, and toward working with geometric shapes and patterns.

But then when he transitioned into working with neon and with interior spaces like walls he entered a different realm, one in which his art was interacting in a personal, tactile way with his viewers. And as he then went on to make more public art, the idea of abstraction seemed to melt entirely away, as these so-called abstract works in fact inhabited a most assuredly realistic place in the world.

Through much of Morellet’s work, we come to the conclusion that now abstraction and reality are one. As evidenced in his Geometree series, the physical, natural and representational realm melds seamlessly into the realm of abstract geometry and flattened space. Our world of modern aesthetic phenomena encompasses both abstraction and figuration simultaneously.

Whether this was his intent or not is unknown, but by the end of his career Morellet proved that the so-called abstract visual language of circles, triangles, squares and lines is as much a part of our contemporary world as the visual language of trees, houses, faces, animals, sunsets and hills. This demonstration of the cooperative forces of light and dark, dimensionality and flatness, abstraction and figuration, this is the most important gift Morellet left behind for future generations of artists. Through his enigmatic legacy, his humor and the sincerity with which he worked, he taught us what art can become if it stays open, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and remains free.

Featured Image: François Morellet - Still from François Morellet’s Reflections in water deformed by the spectator, 1964

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio