The Art of František Kupka - From Figuration to Orphism

What is color? What is its purpose? What are its capabilities? It may sound strange, but there is much we do not know about the underlying phenomena that cause us to experience color. For example, is color only visual? Or do its properties transcend aesthetics? František Kupka was one of a group of abstract artists in the early years of the 20th Century that thought seriously about the essential nature of color. Rather than using color simply as a way to add aesthetic value, Kupka made color itself the subject of his paintings. By freeing color from its associative role he was able to examine its abstract potential. This may seem like an esoteric pursuit, but for Kupka it had wide-ranging implications in both the visual, and mystical realms.

František Kupka Discovers Abstraction

When František Kupka enrolled in art school in 1889, his focus was on figurative painting. He mastered classical techniques while studying in academies in Prague, Vienna and Paris. By the early 1900s he was a successful illustrator for Parisian newspapers and was exhibiting figurative paintings in exhibitions. But back in 1886, three years before Kupka started school, the painters Georges Seurat and Paul Signac had discovered a technique known as Pointillism that would soon change the way Kupka approached painting. Also called Divisionism, this technique involved placing unmixed colors next to each other on a canvas rather than mixing the colors beforehand, allowing the human eye to do the mixing, resulting in more luminosity than if the colors had been mixed prior.

Divisionism influenced the Italian Futurists, who modified the concept into Dynamism, placing forms next to each other in space in such a way as to trick the mind into perceiving motion. Divisionism also influenced the Cubists, who applied the concept to dimensional space, separating an image into multiple simultaneous viewpoints then combining the viewpoints into a multi-planed image of four-dimensional reality. When Kupka read the Futurist Manifesto in 1909 and encountered the works of the Analytical Cubists in Paris around the same time, he too became inspired by Divisionism. But rather than applying it toward a figurative goal, he used it to explore the abstract dynamic possibilities of pure color.

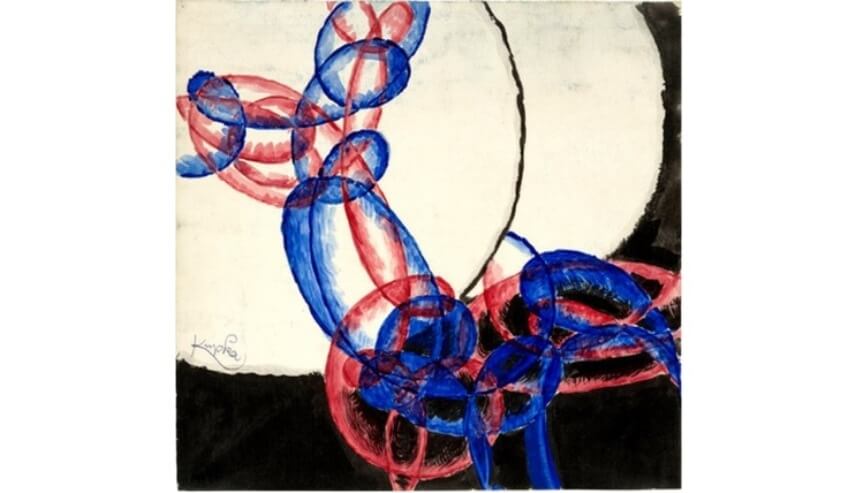

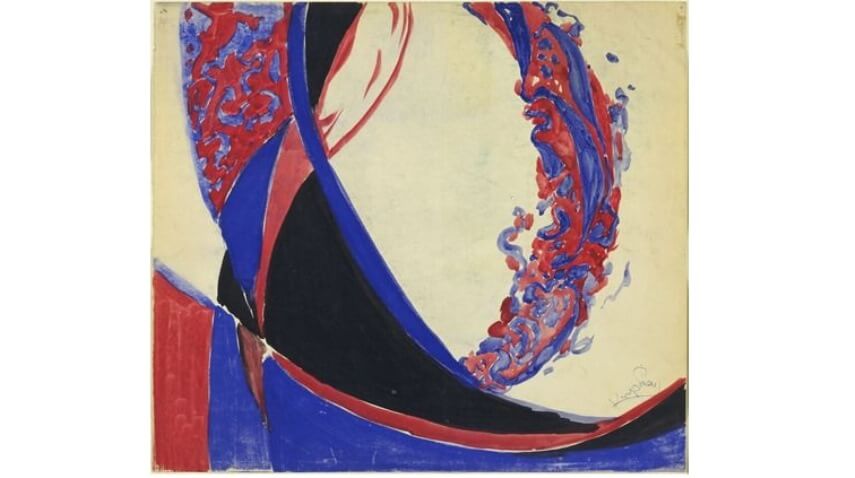

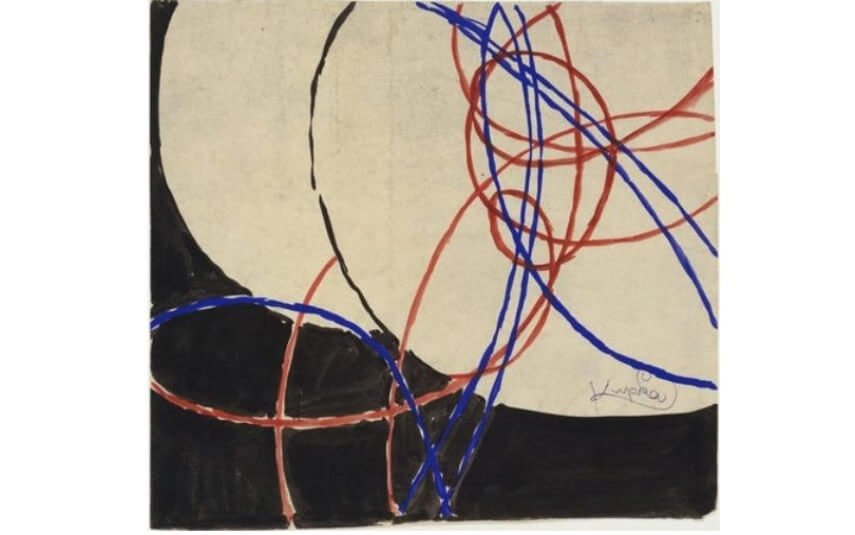

František Kupka - three studies for Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colors, 1912, © František Kupka

Interrelated States of Being

Joining Kupka in his examination of color were the painters Robert and Sonia Delaunay. Together they became known as the Orphists. The goals of Orphism had to do with discovering how colors interacted with each other, and the various emotional and psychological effects that could emerge from different color combinations. One theory they explored was the vibrational quality of colors. Another examined how colors are perceived differently depending upon which colors they are next to. They called their achievement Simultanism, correlating it with the various simultaneous transcendental states of being they believed a viewer could experience while interacting with an Orphist composition.

They were also interested in the ways color might correspond to music. To build his own theoretical foundation for purely abstract painting, Wassily Kandinsky had already been writing about the capacity music had to communicate abstractly without recognizable words, and the connection that might have to the capacity for paintings to communicate without recognizable imagery. Beginning around 1910, Kupka explored this idea in a series of studies featuring adjoining colors swirling together in circular, lyrical compositions. These studies culminated in what became known as his visual manifesto, a painting he exhibited at the 1912 Salon d’Automne, one of the first fully abstracted paintings ever to be shown in Paris. In a nod to the connection between the abstract potential of music and color, he titled the painting Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors.

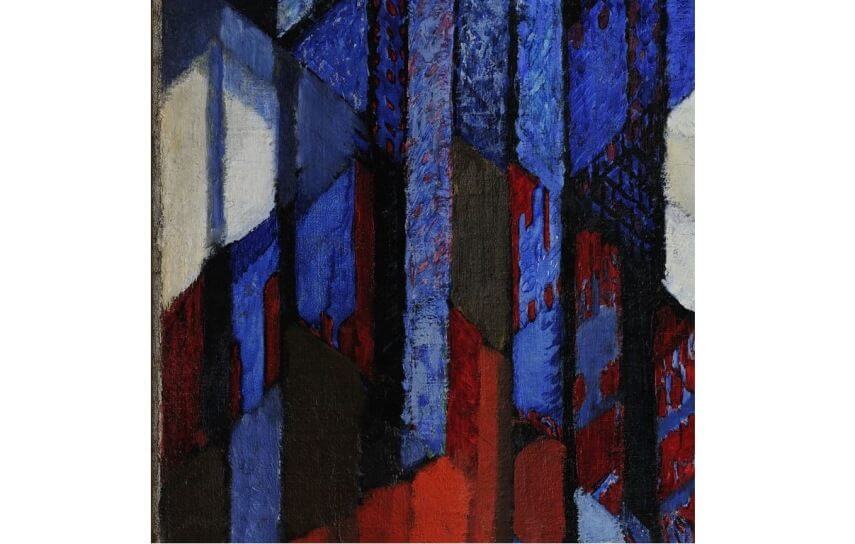

František Kupka - Katedrála, 1912-1913, oil on canvas, 180 x 150 cm, Museum Kampa, Prague, Czech Republic, the image is part of a set of tiles which combine to form a complete image

Inner Experiences

Most of us take color for granted. We assume that the experience of color is universal, and that even if we disagree on a hue it is because of differences in our eyes or the ways our brains interpret stimuli. But maybe there is more to color than meets the eye. Maybe color is not objective. Maybe color adjusts itself according to its observer. People with the rare neurological condition called synesthesia often do not even see color at all: they taste color, smell color or even feel color. Which brings us back to the question: What is color?

František Kupka and the Orphists believed there was something rich and meaningful to be discovered through the exploration of this question. They believed that by presenting compositions of pure abstracted color they had the capacity to open up new dimensions of human experience. Rather than using color simply to designate and decorate, they believed color could affect the inner states of sentient beings. They even felt it could result in the experience of harmony, and profoundly affect the quality of human existence.

Featured Image: František Kupka - Amorpha, fugue en deux couleurs (Fugue in Two Colors), 1912, 210 x 200 cm, Narodni Galerie, Prague

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio