Futurism - Art of the Future Past

Abstraction demands imagination, and imagination demands freedom. Beautiful freedom, that which makes honest self-expression possible. Terrible freedom, that which says anything goes. Freedom was at the heart of Futurism. Artists allied themselves with its principles because they desired freedom from antiquity’s bondage. Under the auspices of Futurism, art could take on any characteristics imaginable. It could be abstract. It could be imperfect. It could be absurd. It could take whatever form was imagined by what F. T. Marinetti called “the young, the strong, the living Futurists.”

The Joy of Mechanical Force

The automobile could practically be considered ancient technology. Self-propelling, passenger-carrying street vehicles have existed in some form since 1768. But it wasn’t until 1886 that Karl Benz invented the first gas-powered production car, making high speed individual travel a reality for anyone with the financial means to own one. The Italian writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was one such privileged individual, and he was enchanted by how gas-powered cars provided regular humans with the ability to attain high speeds. He loved the way the world looked, sounded and smelled when whirring past him from behind a steering wheel.

In 1908, Marinetti crashed his car near Milan while trying to avoid hitting a couple of bicyclists. That incident set off a firestorm in Marinetti. Bicycles were slow and reminiscent of the past. The automobile was fast and prescient of the future. From Marinetti’s perspective, the past had gotten in his way and almost killed him. He decided, at least philosophically, that next time the past got in his way he would run it down. He wrote about his car accident in dramatic, poetic detail in an essay called The Joy of Mechanical Force, using the story as metaphorical justification for the destruction of history. That essay was published in Italian and French newspapers in February of 1909, presented as the first half of the document known as the Futurist Manifesto.

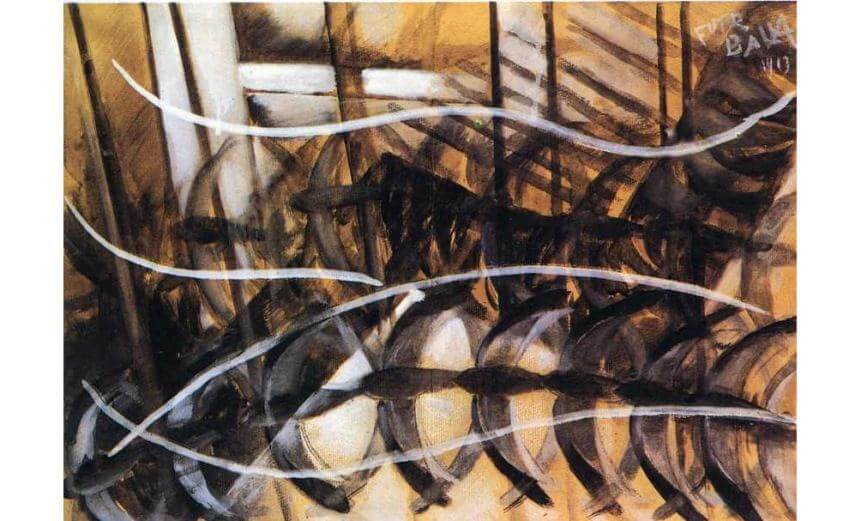

Giacomo Balla - Flight of the Swallows

Futurism, Art and Fascism

In his Futurist Manifesto, Marinetti passionately advocated for courage, daring, creative freedom and the embrace of speed. He argued that too much attention was being paid to old artistic traditions while living artists were discouraged or even ignored. He wrote, “we want to deliver Italy from its gangrene of professors, of archaeologists, of guides, and of antiquarians. Italy has been too long a great secondhand brokers' market.” Many artists in many countries, especially those working toward making purely abstract art, shared Marinetti’s viewpoint.

Strangely, Marinetti also advocated for violence, war and misogyny in his list of Futurism’s goals. He wrote, “We want to glorify war -- the only hygiene of the world -- militarism, patriotism, the anarchist's destructive gesture, the fine Ideas that kill, and the scorn of woman. We want to demolish museums, libraries, fight against moralism, feminism, and all opportunistic and utilitarian cowardices.” While many artists owe a debt to the first part of his manifesto, which contributed to great artistic freedom, the second part sadly led directly to a mindset that enabled the rise of fascism.

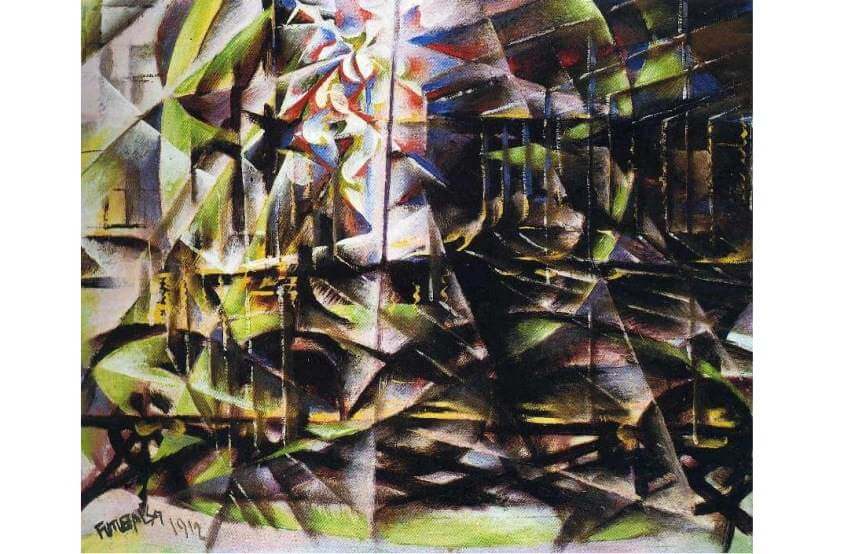

Giacomo Balla - Speeding Automobile, 1913, Oil on canvas, 56 cm x 69 cm

The Futurist Artists’ Manifesto

In 1910, five Futurist artists – Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla and Gino Severini – set out to establish specific aesthetic guidelines for Futurist art. They published the Manifesto of the Futurist Painters, which advocated directly on behalf of abstraction, stating, “The Portraitists, the Genre Painters, the Lake Painters, the Mountain Painters. We have put up with enough from these impotent painters of country holidays.”

It continued, “With our enthusiastic adherence to Futurism, we will: Destroy the cult of the past, the obsession with the ancients, pedantry and academic formalism. Totally invalidate all kinds of imitation. Elevate all attempts at originality, however daring, however violent. Bear bravely and proudly the smear of “madness” with which they try to gag all innovators. Regard art critics as useless and dangerous. Rebel against the tyranny of words: “Harmony” and “good taste” and other loose expressions which can be used to destroy the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Rodin...Sweep the whole field of art clean of all themes and subjects which have been used in the past.”

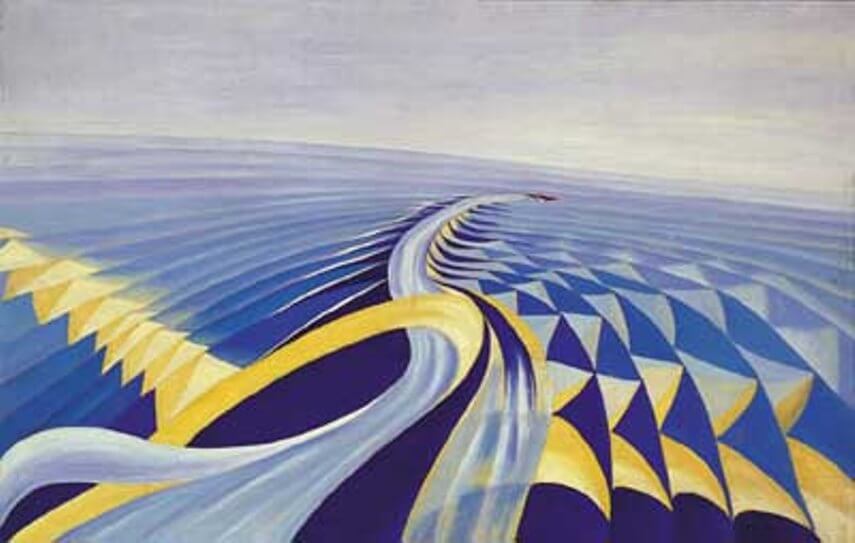

Benedetta Cappa - Velocità di motoscafo (speedboat), 1924, Oil on canvas, 70 x 100 cm, Galleria d’Arte Moderna

Futurism Art Rises

The painter Umberto Boccioni was one of the main architects of the Manifesto of Futurist Painters. A student of Giacomo Balla, Boccioni was trained in Divisionist techniques. He was interested in how the mind could “complete” a picture through interpretation of abstract elements. After traveling to Paris and encountering the Cubists, he dedicated himself to expanding on their ideas. Through abstraction he endeavored to portray the fantastic nature of the motor-driven age. He wrote, “we synthesize every moment (time, place, form, color-tone) and thus paint the picture.” One of the most prolific painters, thinkers and writers of his time, Boccioni died in 1916 at age 33, just as his ideas were beginning to flourish.

Boccioni’s teacher Giacomo Balla was focused on one main concept: Dynamism. The word dynamism refers to action. It expresses the combination of speed, movement and sound. While the Cubists were attempting to express four-dimensional perception by portraying multiple perspectives and planes simultaneously, Balla wanted to capture more vitality. Whereas Divisionism asked the viewers eye to mix colors, Balla deconstructed other elements of an image, such as color, line, surface and form, and created pictures that asked the eye and the mind to make other kinds of connections. His efforts were inherently abstract as they endeavored to portray the perception, or the essence of life rather than portraying a representational image of it. His paintings Flight of the Swallows and Speeding Automobile, both made in 1913, capture his ideas.

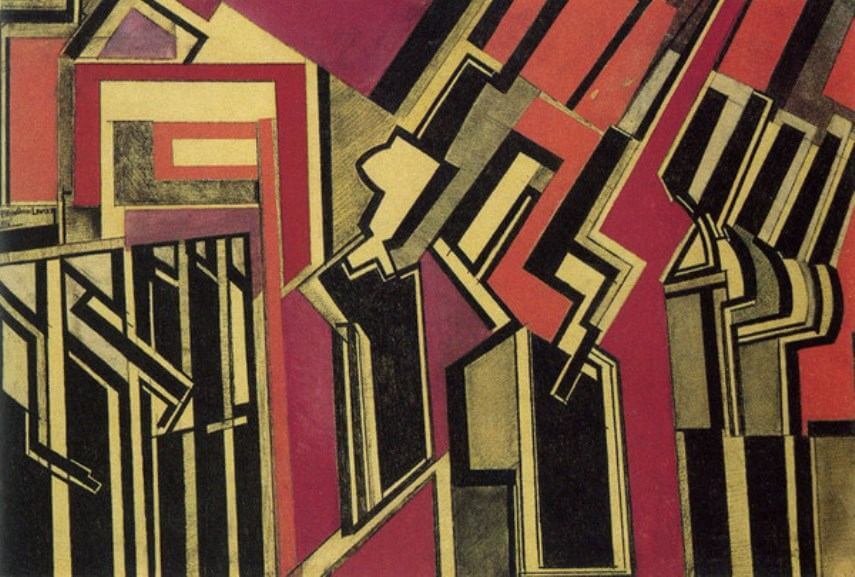

Wyndham Lewis - Vorticist painting, Red Duet, 1914

Key Elements of the Abstract Futurist Style

Futurist painters focused on a palette of bright, unreal colors. They placed colors next to each other for their emotional effect. They used sharp angles and strong lines to convey the sensation of light and speed. They embraced chaos and disarray within their images, manifesting a new, urban, modern, technologically influenced aesthetic.

Their deconstructed, confident style directly influenced a large number of abstract art movements, cementing the trend toward abstraction that was simultaneously evolving in multiple cities and nations. It gave rise to Rayonism, a style primarily explored by Russian abstract painters, which focused on extreme angles and colors in an attempt to convey the essence of light. It inspired Aeropainting, a specific subset of second-generation Futurist painting that focused on depicting abstracted aerial landscapes. It also helped support the theoretical foundation of movements such as Fauvism, Suprematism and Constructivism.

Joseph Stella - Battle of Lights, Coney Island, 1913, Oil on canvas, 195.6 × 215.3 cm. Gift of Collection Société Anonyme. 1941.689. Yale University Art Gallery. Photo credit: Yale University Art Gallery

Futurism’s International Influence

The aesthetic interests of the Italian Futurist artists were a direct inspiration to many international artists and movements. In Britain, the painter Wyndham Lewis built on the ideas of both Futurism and Cubism to found a movement he called Vorticism. The goal of Vorticism was to capture movement, speed and modernity, but in a hard-edged, clean style that resulted in flattened picture planes and an aesthetic closer to Constructivism, Suprematism and De Stijl.

Representing the modern American landscape was the Italian-born American futurist painter Joseph Stella. Stella studied art in New York and lived there from 1896 to 1909, but he detested America, and returned to Italy just in time to be influenced by the burgeoning European Modernist scene. After gaining immeasurably from new friendships with, among others, Umberto Boccioni, Gertrude Stein and Picasso, Stella returned to America and transformed his technique to capture New York in an epic and unique Futurist-American style.

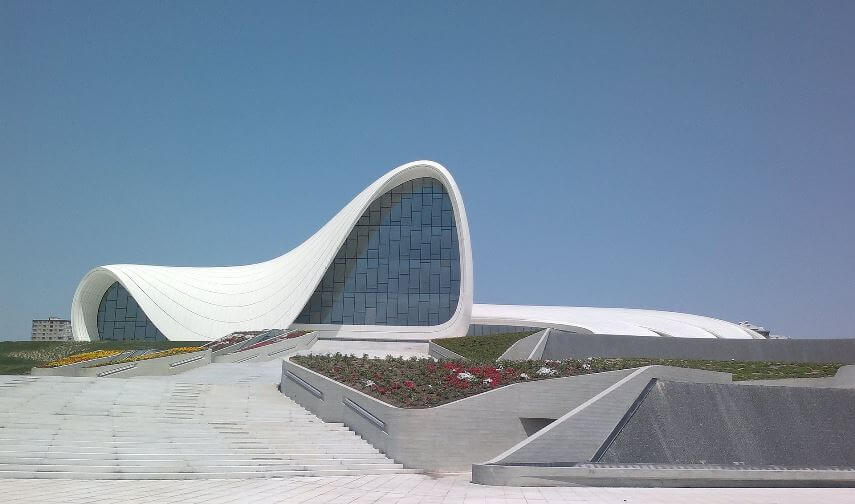

Zaha Hadid - Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre in Azerbaijan

Futurism’s Future

The most powerful legacy of Futurism is its confident rejection of history. After all, what is there for contemporary artists to do if everything worth doing was already done in the past? While the Futurist aesthetic impact may have lasted only a short time, its theoretical impact is what gave courage to the Dadaists in their attempt to radically re-contextualize art. It’s what encouraged the avant-garde thinking of the Surrealists, the Abstract Expressionists and the Conceptual Artists. And it’s what has given strength and inspiration to today’s Neo-Futurists, such as the architect Zaha Hadid, who died in 2016 at age 65.

By poetically and emotionally expressing the desire for freedom from the past, the Futurists emboldened the abstract artists in their fight to be taken seriously. While their rhetoric about violence, war and misogyny was distasteful, backwards and destructive, the aggressive tone of the Futurists may have been necessary in order to break down the barriers that were holding artists back from exploring the full depths of their imagination.

Featured Image: Umberto Boccioni - The City Rises, 1910, Oil on canvas, 199.3 x 301 cm

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio