Bold Color and Geometry in the Painting of Gillian Ayres

The acclaimed British abstract artist Gillian Ayres has been making art professionally for nearly 70 years. Since graduating from Camberwell School of Art in London in 1950, she has never wavered from her one pure passion: painting. Even in the midst of global trends like Conceptual Art, Performance Art, Land Art, Installation Art and Multi-Media Art, each of which challenged the relevance of her work, Ayres remained dedicated to the straightforward proposition of making images with paint. Her work has always been abstract, though her style has continually evolved. When asked about the meaning of her oeuvre, or what the impetus was for any particular work she has created, she redirects the conversation away from words. “It is a visual experience,” she says, “not a literary one.”

A Certain Rattiness

When talking about her early days in art school, Gillian Ayres adopts a sort of sly aspect. She recalls being utterly turned off by the teaching methods of many of her professors. She and the other students were required to spend entire days focused on things such as repeatedly drawing one body part of a model or sketching one scene in front of a London café. She perceived the repetition and tireless precision as mundane. She longed to discover Modernist and abstract art, and to create the type of art that would make her feel alive, vibrant, and free.

She describes herself in those days as subversive. However, she has said, “It’s not an ambition to go against the grain. I don’t think there was a desire to be subversive. I think one just felt ratty.” That rattiness was finally validated in the early 1950s when she encountered for the first time the work of Jackson Pollock. The pictures she saw of him working on the floor, handling paint in a loose, active, living way, inspired her, and she immediately knew she wanted to be free like that. To this day Ayres counts Pollock as a major inspiration; not that she copied his technique, style, or the appearance of his work, but rather that he showed her a path toward breaking out of the classical mess.

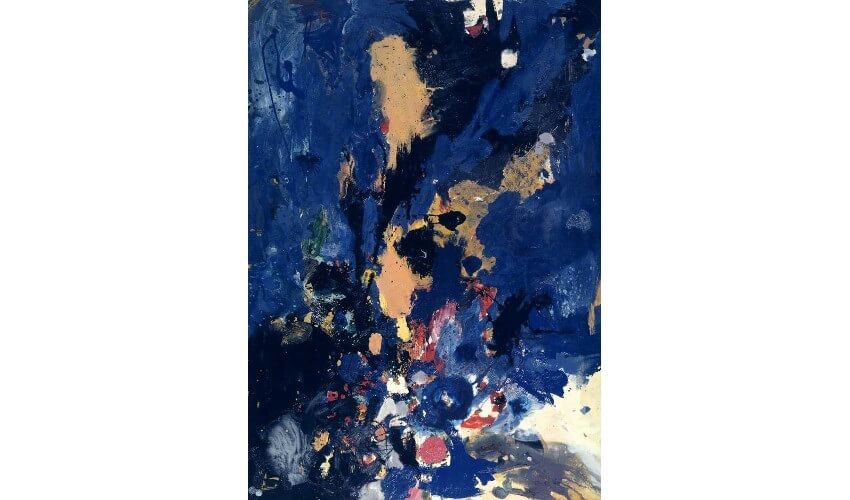

Gillian Ayres - Distillation, 1957. Oil paint and household paint on hardboard. 84 x 60 in. © Gillian Ayres

Gillian Ayres - Distillation, 1957. Oil paint and household paint on hardboard. 84 x 60 in. © Gillian Ayres

A True Calling

Newly emboldened, Ayres spent the 1950s developing a dynamic, vibrant abstract style. But although the work brought her the respect of other painters, and to a small degree the public, Modernism and abstraction still were not yet widely accepted in Britain. She had exhibited and sold a small number of paintings, but financial success eluded her. So she accepted happily when she was offered a temporary position teaching at the Bath Academy of Art, an art school known for being progressive. She ended up staying on at Bath for seven years, then moving on to lecture at Saint Martin's School of Art for 12 years, and to head the painting department at Winchester School of Art for three years.

While teaching, Ayres continued evolving her style. She experimented with biomorphic shapes, explored a range of color palettes, and fluctuated between painterly, impasto works and flat surfaces. And her reputation as a rebel grew, as she continued staunchly advocating for painting when almost all of her colleagues were steering their students toward other, more contemporary media. But then in the late 1970s she had a moment of clarity. After nearly dying from a case of acute pancreatitis, she realized that despite her success as an educator, all she really wanted to do was paint. She promptly wound down her academic career and moved to the countryside of Wales to dedicate herself full-time to her art.

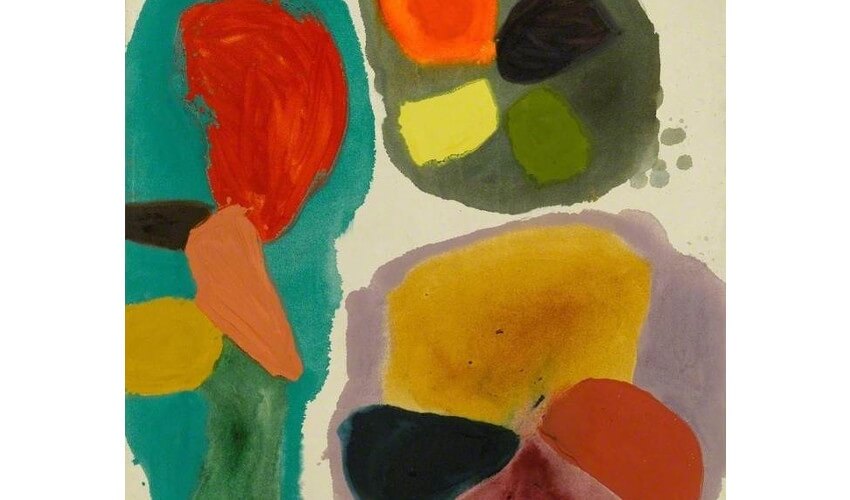

Gillian Ayres - Lure, 1963. Oil on canvas. 152.4 x 152.4 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Gillian Ayres - Lure, 1963. Oil on canvas. 152.4 x 152.4 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Color and Shape

Newly rededicated, Ayres became immersed in her love of paint. She had already been gravitating toward a more impasto, textured style, and now her work became even more painterly, more tactile, and more lush. She used her bare hands to manipulate the paint, connecting directly, personally with the surfaces. Her paintings from this time seem like primordial breeding grounds for new color relationships and unimagined shapes. Innumerable possibilities burst forth out of the ecstatic compositions, somehow achieving harmony despite their complexity.

It was around this time that Ayres realized that she no longer had any interest in tone. She wanted nothing of muted hues, or nuances in color. She wanted intensity. And along with her focus on vibrant, pure color, she also began gravitating toward a more figurative use of shape, hardening her lines and allowing larger fields of color to inhabit her compositions. A sense of calm confidence emerged in her paintings, perhaps relating to a life now spent in constant contemplation of the essential work she felt born to do.

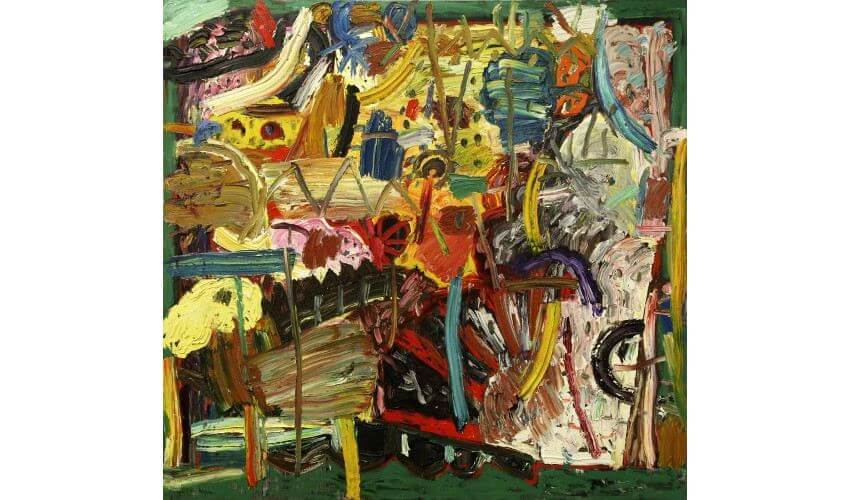

Gillian Ayres - Aeolus, 1987. Oil on canvas. 213 x 213 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Gillian Ayres - Aeolus, 1987. Oil on canvas. 213 x 213 cm. © Gillian Ayres

A New Geometry

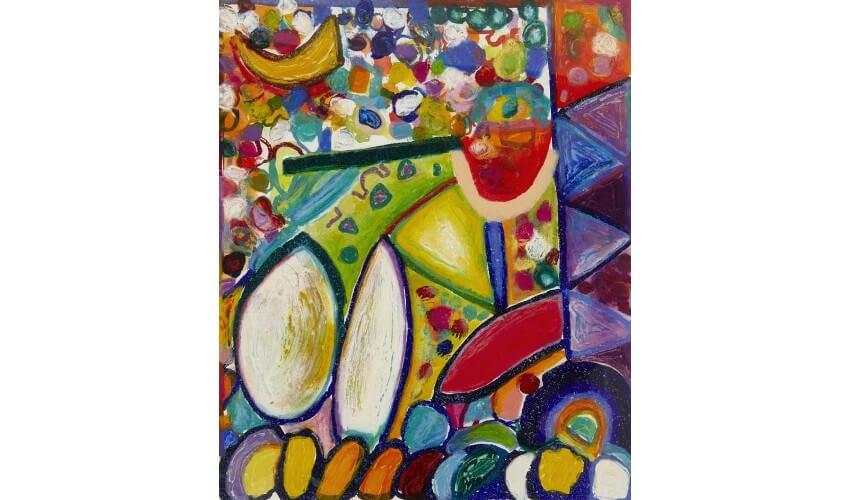

Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Ayres continued to evolve farther still toward a sense of recognizable shapes in her compositions. Hints of natural objects appear and disappear, such as a moon or a sun, a horizon line, or a worldly assortment of shapes akin to feast on a table or flowers in a field. Some of her compositions flirt with geometric shapes and patterns, even if only in fragments. But it is still not so much realistic figuration that has emerged in her most recent works as it is like a figurative abstract visual language has asserted itself, akin to what materialized when Matisse, in the later phase of his career, developed his iconic hard-edge cutouts.

This visual language happens to lend itself particularly well to the medium of printmaking, which has long interested Ayres. In recent years she has been enjoying making prints and woodcuts during the winter months in her studio. The colors in her prints are more vibrant and pure than ever, creating bold relationships that shock the eye with their dynamic presence. She refers to the printmaking process as something that connects with the drive to reproduce. But despite its essentially reproductive quality, she tends to add hand-painted elements to many of the prints she makes, making each work of art unique. This fusion of mechanical processes and hand painting results in a layered mixture of textures.

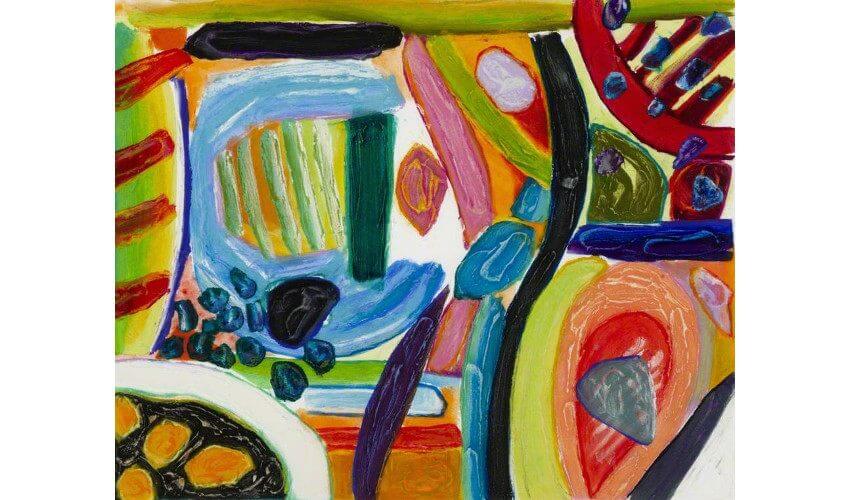

Gillian Ayres - Rombuk, 2001. Liftground & aquatint with carborundum (Silicon carbide) & hand painting on paper. 68.6 x 78.7 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Gillian Ayres - Rombuk, 2001. Liftground & aquatint with carborundum (Silicon carbide) & hand painting on paper. 68.6 x 78.7 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Boundless Innovation

In an age when technology and multi-media practices seem to be at the forefront of every art fair and biennale, and when overtly social, cultural and political work garners much of the attention of the media, it is an accomplishment that Gillian Ayres has continued to prove abstract painting is always relevant. She has withstood the pressure of innumerable trends, all the while remaining true to her simple love of color, shape, surface and paint. In the tradition of the Modernist masters who inspired her, like Picasso, Matisse and Miro, Ayres has demonstrated the value of painting by showing simultaneously how simple and how varied it can be.

And yet despite her single-minded love of the medium, her aesthetic vision and her habits have continually progressed. She has worked variously with a range of different painting mediums, exploring and embracing the medium specificity of each. And by expanding her practice to include printmaking processes she has stretched the boundaries of painting whenever she could. She has proved herself to be complex, and yet by reducing the elements of painting down to color, shape and space she has taught multiple generations of viewers how to simply look. “One worries terribly, in a fidgety sort of way,” she says. “I want to find something, and I want my paintings to be uplifting, but I don’t think I know how to finish a picture, and I don’t know how to start either. People like to understand, and I wish they wouldn’t. I wish they would just look.”

Gillian Ayres - Finnegan's Lake, 2001. Liftground & aquatint with carborundum (Silicon carbide) & hand painting on paper. 55.9 x 45.7 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Gillian Ayres - Finnegan's Lake, 2001. Liftground & aquatint with carborundum (Silicon carbide) & hand painting on paper. 55.9 x 45.7 cm. © Gillian Ayres

Featured image: Gillian Ayres - Sun Up (detail), 1960. Oil on canvas. © Gillian Ayres

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio