The Story of Hedda Sterne, Between Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism

Nov 26, 2018

Hedda Sterne was a versatile and imaginative artist who experimented with dozens of distinct styles over the course of her long career. Yet her legacy has somehow become attached to a single style—Abstract Expressionism—and a single group—the Irascibles. It is an ironic fate. Sterne never associated herself with the aesthetic qualities nor technical aspects of Abstract Expressionism, nor was she particularly invested in the cultural critique implied by her association with the Irascibles. These associations arose mostly because she was friends with many of the New York School artists and her work was exhibited in some of their early shows. Because of those connections, she ended up signing a notorious letter to the president of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1950 denouncing the conservative curation of an exhibition of American art. Some of the artists who signed the letter posed for a picture that was printed on the cover of Life magazine. That group was later dubbed “The Irascibles,” a term later used synonymously with Abstract Expressionist artists. Sterne was the only woman in the photo, although two other female artists—Louise Bourgeois and Mary Callery—had also signed the letter. Her position in the back of the photo standing on a table high above the 17 men made her an iconic presence. The picture dogged her for the rest of her life. Every time she evolved her style, she had to hear the same questions about why she no longer made art like she did in the 1950s, despite the fact that even in the 1950s she had changed her style at least three or four times. The myth annoyed Sterne, but she also had a sense of humor about it. As she said late in life, “I am known more for that darn photo than for eighty years of work. If I had an ego, it would bother me.”

Automatic Collage

If Sterne had gotten the chance to undo her association with Abstract Expressionism and attach herself to another movement, she would likely have chosen Surrealism. That was the method into which she was born and raised. Its emphasis on intuition, imagination, and the power of dreams was ultimately what guided every other artistic choice she ever made. Born in Bucharest, Romania, in 1910, she started taking art classes at age eight. Her first art teacher was the naturalist sculptor Frederic Storck, but by her late teenage years she was studying under the tutelage of Marcel Janco, the co-founder of Dadaism, and the Surrealist painter Victor Brauner. In her early 20s, she began traveling frequently to Paris. That is where she met and studied with the Cubist painter André Lhote as well as Fernand Léger, a Cubist who is also considered to have been a forefather of Pop Art.

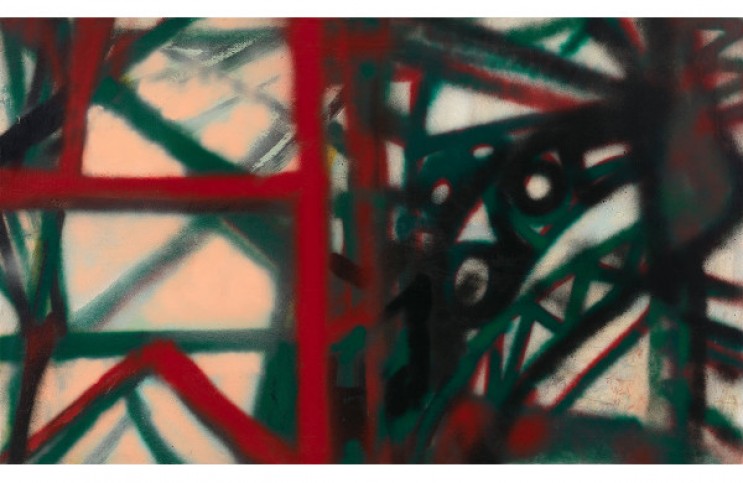

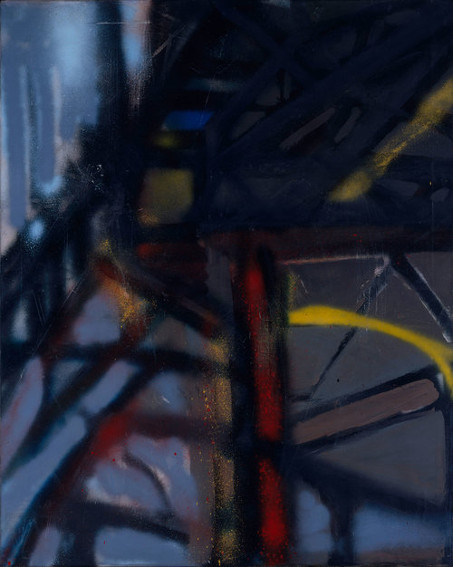

Hedda Sterne, Third Avenue El, 1952-53, Oil and spray enamel on canvas, 40 3/8 x 31 7/8 in., Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Daniel H. Silberberg, 1964 (64.123.4). © The Hedda Sterne Foundation

Building from these diverse influences, Sterne developed a unique method based on automatic drawing in which she tore up paper and dropped the shards intuitively, creating automatic collages. After seeing some of her collages in the 11th Exposition du Salon des Surindépendants in Paris, the famous Dadaist Hans Arp introduced Sterne to Peggy Guggenheim, who exhibited her work in her galleries in Paris and London. When Sterne fled Europe in 1941 at the start of World War II she came to New York, where Guggenheim welcomed her into the community of American artists with whom she was connected. The Guggenheim connection established Sterne in the New York art scene, but it was the gallerist Betty Parsons who truly took Sterne under her wing. Parsons gave Sterne her first solo exhibition at the Wakefield Gallery in 1942, and when Parsons opened her own gallery four years later Sterne was one of the first artists she signed. Most importantly, Parsons understood the value of experimentation. She helped foster in Sterne the belief that she was free to explore whatever style she wanted without feeling beholden to any one particular path.

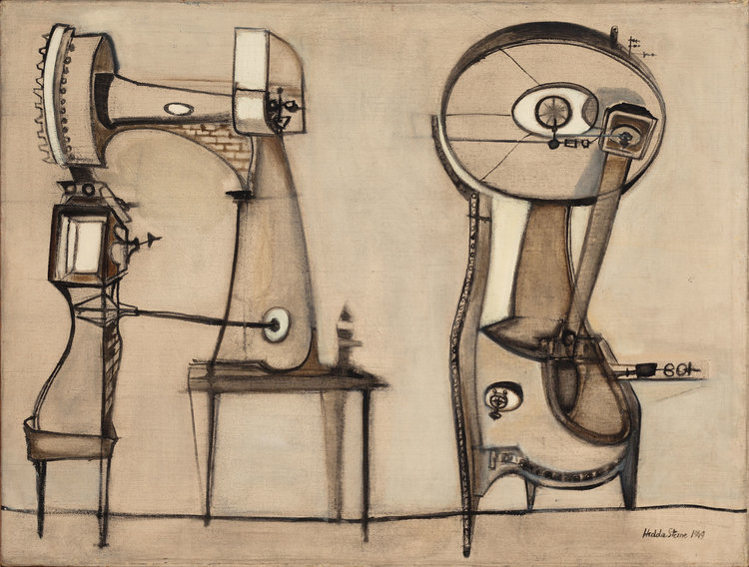

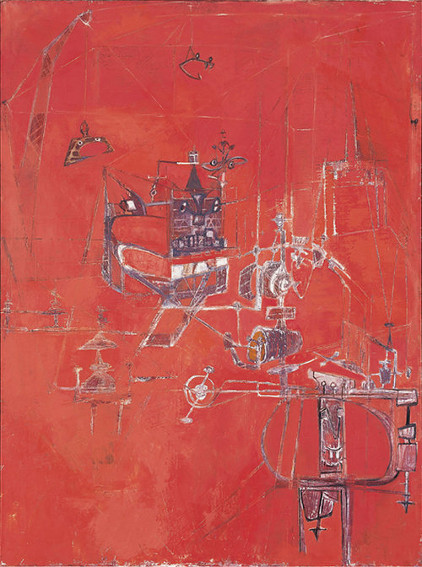

Hedda Sterne, Machine (Anthropograph No. 13), 1949, Oil on canvas, 30 in. x 40 in. © The Hedda Sterne Foundation

Proto-Graffiti

Her arrival in America had a profound effect on the way Sterne saw her relationship to images. She translated the phenomenal range of sights and colors she saw into fantastical compositions that straddled the boundaries of figuration and abstraction. She painted pictures of the world, but altered them to convey the way she felt. Most impactful on her was the incredible array of machines she saw, from farming machines on her trips to the country to industrial contraptions in the city. She portrayed these objects in Surrealist compositions such as the whimsically figurative “Machine (Anthropograph No. 13)” (1949) and the hauntingly fantastical “Machine 5” (1950). These, incidentally, were the paintings Sterne was making when she was included in the Irascibles photograph. They are nothing like the work of any of the men in the photo.

Hedda Sterne, Machine 5, 1950, Oil on canvas, 51 x 38 1/8 in., Collection of Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Festival of Arts Purchase Fund, 1950-7-1. © The Hedda Sterne Foundation

In 1952, Sterne made one of her most fascinating innovations—painting with an acrylic spray gun. Although today acrylic spray paint is an iconic element of street art, both spray paint and acrylic paint were only invented in the 1940s. Sterne was one of the first artists to grasp the unique urban qualities of the medium. She used it to show the fast pace and dynamic visual qualities of New York in “Third Avenue El” (1952), a gestural, splotchy, abstracted vision of life beneath elevated train tracks that would look at home on the side of any New York subway car in the 1980s, or the walls of any modern street art gallery. In the 1960s, Sterne changed her style to atmospheric color fields and portrayals of dreamlike, biomorphic forms floating on flattened planes. In the 1970s, she created an epic painting titled “Diary” that included hundreds of hand written literary quotes. In the 1980s, she painted kaleidoscopic abstractions evoking crystalline tunnels or journeys into Cyberspace. When she later developed eye problems she painted white on white visions of the blots she saw. Perhaps her constant innovation stopped her from achieving the notoriety of her contemporaries, but it also sustained her in crucial ways. Sterne painted until she was 94. When she died in 2011 at age 100, she had established herself as one of the most innovative and imaginative artists of her generation. She also outlived, outlasted and outperformed all of her contemporaries—about as un-irascible an artist as there ever was.

Featured image: Hedda Sterne, New York, N.Y., 1955, 1955, Airbrush and enamel on canvas, 36 1/4 × 60 1/4 in., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Gift of an anonymous donor, 56.20. © The Hedda Sterne Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio