Louise Bourgeois Art and the Reduction of Form

To those who see abstract art as a path toward a more introspective and fulfilling life, Louis Bourgeois was the embodiment of an ideal. But not because of her honors or awards, or the celebrity she achieved: quite the opposite. It is because Louis Bourgeois art speaks to what is relevant to our everyday lives. To paraphrase Gichin Funakoshi, the father of modern karate, when we realize how something relates to our everyday lives, that’s when we discover its essence. The art world is too often defined by manifestoes and divided up into movements, eras and styles. Artists are too often categorized by gender, race, nationality and educational pedigree. We easily forget that art’s true value exists beyond such petty considerations. The artwork of Louise Bourgeois confidently rises above classifications. Her aesthetic contribution earnestly inhabits a space that is both figurative and symbolic. It is grotesque and yet sublime. She explored every imaginable discipline, never attaching herself to any particular trend, and yet invented a few trends along the way. Over the course of a seven-decade career she achieved what few other abstract artists have: she made personal artwork that was universal.

Contradictory Forces

Louise Bourgeois was born into a family of contradictions. Her father was a successful provider, but he was also the biggest threat to Louise’s security. Her parents were partners in business and in life, yet her father unapologetically engaged in sexual affairs that threatened the stability of both. Louise’s live-in nanny and tutor, supposedly a protector and guide, was in fact her father’s mistress. Louise’s mother, a weaver for the family textile business, was a loving, protective force and was her fiercest advocate, but was also physically weak and eventually died young.

Throughout the entirety of her youth Louise witnessed the daily brutality of a home that was simultaneously defined by and threatened by affection. She experienced the raw truth about the frailty of human character. She felt jealousy, rage, fear, loneliness and confusion. Yet she never wanted for shelter, food, clothing or schooling. She was loved and cherished, at least by one parent. When her mom died, Louise was 21 and was studying math at university. Rather than continuing on that path, which was her father’s desire for her, Louise was inspired by her mother’s passing to dramatically change her life. She forged a path that would allow her to confront and express her feelings. She abandoned math and devoted herself instead to living the life of an artist.

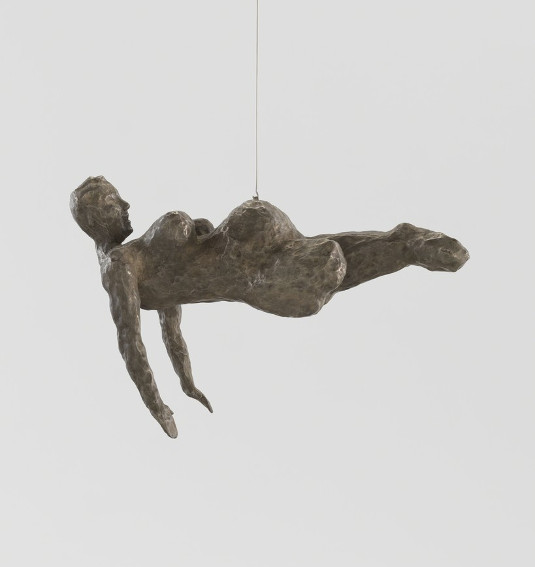

Louise Bourgeois - FEMME, 2005. Bronze, silver nitrate patina. 13 × 16 1/2 × 7 3/4 in; 33 × 41.9 × 19.7 cm. © 2018 The Easton Foundation

Symbolism and Psychotherapy

For six years after her mother died Louise studied art and earned a hands-on education by visiting the studios of successful artists and assisting with their exhibitions. At the age of 27 she briefly opened a shop in a corner of her father’s textile store, selling art prints. He allowed her to utilize the space since it was a business venture. One day in the shop she struck up a conversation with a collector. Then, as she put it, “between talks about surrealism and the latest trends,” they got married.

That collector happened to be Robert Goldwater, a respected art historian from America. Robert and Louise moved to New York where Louise continued to study art and expanded the range of her aesthetic production. Influenced by Surrealism and the concept of psychotherapy, Louise turned to her traumatic childhood for subject matter for her art. She developed a symbolic language of forms based on a combination of her memories and her dreams.

Louise Bourgeois - Give or Take (How Do You Feel This Morning), 1990. Cast and polished bronze sculpture. 4 1/2 × 9 × 6 in; 11.4 × 22.9 × 15.2 cm. Edition 5/20. Caviar20, Toronto. © 2018 The Easton Foundation

The Symbolism of Louise Bourgeois

Louise’s symbolic visual language consisted of personal imagery that for her held obvious meaning. But to viewers, her art seemed savage, bold, abstract and even shocking. One of Louise’s most common symbolic forms was the spider. Beginning as early as the 1940s, Louise incorporated spiders and webs into drawings and prints, and even produced a series of abstract, web-inspired crochet works. She explained that spiders were a symbolic reference to her mother. Her mother was a weaver, and like her mother was, spiders are protectors since they eat mosquitoes, which spread disease.

Eventually her spider forms took on a monumental scale, reaching an apex with a 9-meter tall sculpture titled Maman. In addition to spiders, Bourgeois’ symbolic visual language included cages, houses, male and female genitalia, domestic items like chairs and clothes, and she also often portrayed biomorphic forms that resemble body parts. One of her most famous works is titled The Destruction of the Father, and features a selection of objects resembling organs and flesh spread out on a table, surrounded by orbs evoking a giant open mouth full of teeth.

Louise Bourgeois - Spider, 1997. Steel, tapestry, wood, glass, fabric, rubber, silver, gold and bone. 177 × 262 × 204 in; 449.6 × 665.5 × 518.2 cm. © 2018 The Easton Foundation

Isolated Together

The common thread running through all of Bourgeois’ work is that all of her images relate to her private, personal experiences. One of the most powerful feelings she sought to share with her viewers was that of the interplay between togetherness and isolation. In the 1940s, she created a series of sculptural forms that referenced various people she knew. She exhibited the forms in ways that seems random. But gradually, when looking at the arrangements, the individual forms begin to express their characteristics and each takes on an individual personality until a sense of interaction evolves between them.

Feelings of togetherness and isolation are also integral to a series of sculptural objects Bourgeois made in the 1950s, a time when she was focused on the softer side of life inspired by her husband and children. Objects such as Night Garden, Cumul I and Clamart Other each portray a gathering of forms. The gatherings seem organic, yet they also appear to portray entities that have huddled together for protection or comfort.

Louise Bourgeois - Knife Couple, 1949 (cast 1991). Bronze and stainless steel. 67 1/2 × 12 × 12 in; 171.5 × 30.5 × 30.5 cm. Hauser & Wirth. © 2018 The Easton Foundation

Beyond Labels

Though many of Bourgeois’ works seem figurative, the essence of her work is that it is symbolic and personal. She often portrayed nudity and focused on the female form, but she was assertive in denying any social or political statements in her work. She was female, and sexuality was a powerful force in her upbringing; there was little or no social or political agenda intended in such imagery. Nonetheless, because of the powerful images in so much of her work, she has frequently been identified with feminist and LGBTQ art. Though she may not oppose such representation if she were alive today, she also clearly stated that her objective was not to address any of these issues in her work. She once said, “My work deals with problems that are pre-gender. For example, jealousy is not male or female.”

It makes sense to consider Bourgeois’ work on a personal level. After all her symbolism is relative to her own experiences. Nonetheless each of us can find something in it to relate to. If we are open, we can accept it from the perspective of a larger wisdom. When we can see a body and not think in terms of male or female, we become less isolated and more universally human. When we allow ourselves to gain from both the suffering and the love of our fellow human being, the end result is value added to both their experience and our own.

Featured Image: Louise Bourgeois - Arch of Hysteria, 1993. Bronze, polished patina. 33 × 40 × 23 in; 83.8 × 101.6 × 58.4 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2018 The Easton Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio